Of course it is possible to engage in two or more conversations at once or to channel remotely the voice of another, it is ostensibly a matter of slippage.So it says in the middle of one of Cat Woodward's prose poems on the dawning of the age of aquarius. And she's right, that is possible. In fact we do it a lot of the time but it is not unproblematic. The core of poetry - the poetry project, if you like - doesn't change very much. It deals with the core realities, such as those I mentioned in the last post and it strives to understand them and offer them up as form, a form that has the peculiar grace composed of both excess and inadequacy. Form adapts and changes but the project remains the same.

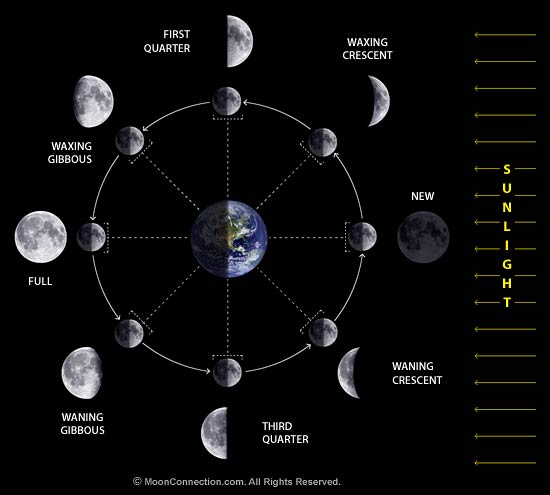

In the first poem of the pamphlet we meet one of the abiding themes of poetry: the moon. The prose poem titled i love the moon makes several references to its subject from the first phrase (the poem is unpunctuated) where "the moon rises over a tree with a robot's muteness half way between gutspill and mind your god damn business" through the text. The moon has "something of an institutionalised relationship with the sun at this moment the sun is breathing into the moon's mouth and saying open your lips you idiot". The moon has the same look as the poet's dead grandmother "only she's been there with that look on her yellow face as if she were dreaming too". The moon "takes her by the hand with a decisive action". Finally "the moon is a dry river she is airless and pale and far after all she is the moon".

Some of these actions are perfectly traditional in a romantic sense, so the poem speaks of trees, femme fatales, nightingales and dreams, but it is looking to extend and intensify the experience of moonness, so it also provides us with robots, fashion models, bodily cavities, sexual contact, dollars, and, finally family history via the grandmother who enters the poem about two thirds through and remains there, becoming a twin subject, perhaps the discovered alternative meaning of the subject. The grandmother effectively anchors the moon for us.

This is, of course, a simplified description of one poem, not the analysis of a 'method' or even a 'vision' if by that we mean the apprehension of some kind of system that informs everything within it. The poem takes up most of the page. It sprawls a little and throws in some rhetorical devices, mostly those that de-romanticise the subject. Nevertheless it refers to intense emotions and an intensity of experience. Blake's moon, Shelley's moon, any poet's moon, depends on similar experiences.

If there's not exactly a method there is a general desire to play and disrupt, to avoid the cosy by cutting or disengaging. In the second poem (this time in lines) on looking for one's enemy and finding her she talks of "concocting a sort of doorway that cannot be passed through". But whatever is beyond the door will keep pressing through our way. Her third poem, sayonara suckers, asks three times for pain to be taken away. The poem talks of cruelty. Its imagery runs a gamut of flash-up scenes involving animals. The scenes are linked, not in narrative fashion, but in terms of register.

All the prose poems work on the same essential principle - some repeated term that sets the key discovered among a series of disruptions or rhetorical tropes. In hello jerk face we are given strings of adjectives, one piled on another. These have a cumulative and essentially alienating effect. The poems really don't want to cosy up to us.

There is a group of haiku too. The haiku is an almost infinitely supple form but in English at least it has a convention of seventeen syllables arrnged 5-7-5. Woodward keeps to that and gains from it. There is no sprawl, no room for extraneous matter. The disruptions are braced against their syllabic necessities. The classical balance is maintained despite the disruptions.

I have concentrated on the first half of this small collection and tried to describe the way it works. Woodward is very inventive and while maintaining a pugnacious front registers delicately and with power. A later poem tender begins:

there is this hoof in himThat is original and beautiful. The poem ends:

a kind of homelessness

made out of parties

how gentle is the finger to the poemI have talked of sprawl in the pamphlet. Some of that is deliberate and necessary but maybe not all of it is. It is difficult producing forms in this way. It depends on an acute ear and a willingness to exceed some inbuilt norms. Woodward certainly has an acute ear. She is working her way to somewhere demanding but rewarding. And there is something beyond intellectual curiosity that is driving the horses. It is not about cleverness, nor is it about obscurity.

how closed the caterpillar to the palm

Which could easily take me back to my little agon with Jeremy Paxman.

No comments:

Post a Comment