Saturday, 30 April 2011

Wedding

I have no firm views about the royal family as an institution: I am not even sure I am entitled to a view. When it comes to the constitution I feel something of a foreigner, a first generation guest. This isn't a rational thought but a feeling, a voice whispering that there are certain respects in which my Britishness is skin deep. It is not that, Voltaire like, I can go back to my home country to write up my views. I could gossip and chat in Hungary, but it would be unformulated, non-ideological, impressionistic. In any case, Hungary isn't my home: Britain is.

I didn't sit down in front of the TV for most of the morning but I did put BBCi on about the time the bride was entering the carriage on the way to Westminster, and kept it on, only stopping it at the interminable vox pops in which repellently aggressive BBC reporters were coaxing ever greater fervour from whichever members of the public they thought could be easily patronised. I am sure Soviet TV reporters worked exactly the same way at the time of the great military parades. I am sure the public feeling in the crowd was genuine, but the coaxing was not. The commentary was hard to get through and I lost count how many times Huw Edwards informed us about the 1902 Landau carriage.

Nevertheless a ceremony is a ceremony and a wedding is a wedding. Furthermore, public interest is public interest. Why watch it? Because most people were watching it. Because to set out not to watch it would have been too deliberate a gesture, especially for someone who has no sense of entitlement. I don't even watch it with ironic interest: it is simply interest, as if to say: So this is where I live. So this too is England. And I remember all the Princess Diana souvenirs in pubs and bars and cafes, aware that there is an engine at work here.

Nor is it in the least an overtly malevolent engine. The presidential-ceremonial role in the Royaume Uni is conducted in terms of royal succession rather than one or other electoral process. It is not the fact that this is quaintly archaic, but the fact that it has a grip on a good portion of the public's imagination that makes it interesting. Princess Diana meant something - rather more than her husband did at one level, though I suspect that if one dug deeper it might be different. The atavistic instinct runs deep in everyone, and here is a place where it is embodied as both symbol and office.

Clearly this does not square with socialist instincts, such as what I have. Succession, symbol and office are aspects of hierarchy and we live in an avowedly and, to a great degree, psychologically egalitarian world. But not in every degree. The security of hierarchy offers a stable identity. You can be proudly working class or claim to be so with pride. Very few people, however, say: I am proud to be poor.

So there are William and Kate undergoing the whole ceremonial arc, the rudiments of which are common to every conventional marriage. 'Princess for a day' is the pattern for everyone else. The princess image runs very deep: not, I suspect in terms of monarchy as such, but on grounds of ceremony and ceremonial treatment. There are few ritually sacramental moments in life: this is the most spectacular. There is even something sacrificial about the role. The bride is the unquestioned star of the event. The best man plays jester. The groom's job is to look presentable and dignified without looking pompous. His bride is displayed before the world. She is the trophy bride before whom he is expected to look a little astonished and abashed. Certainly both William and Kate looked handsome, and reassuringly human.

He mouths to her at the altar: You look beautiful. She smiles back. In this respect it is any human wedding. It is also a moment out of time: what happened before, what is to come is time flowing. This is putting time on hold in order to articulate, or rather to make articulate, the importance of a rite of passage.

Then there is the gathering of the Windsors on the balcony, like a set of royal dolls. Husband and wife kiss once, then again. They move back into the room and the crowd goes. The clothes of the guests have been picked over, their hairdos analysed, their moods considered. Eventually there will be the 'iconic picture'. That becomes the point now. The iconic is a symbol into which various individual selves are poured, and which becomes an element, a part of the weather, in various selves. It also becomes what people call History. The crowds in the street were participating in History. That is why they are there. Not that History will remember them, just as it won't remember most marriages, except as documentary trace or a clutch of faded photos on a market stall.

Friday, 29 April 2011

United fiction versus documentary Charlton

I'm still thinking about the TV play United (only five days old and already in Wikipedia!) and yesterday's Bobby Charlton TV documentary. Over on Facebook, James wonders whether docudrama is an inherently flawed form. Good question.

It is not that docudramas need necessarily fail. Alan Bennett's An Englishman Abroad, and his A Question of Attribution were both very good television productions that might be regarded either as docudramas or as period plays. (Tighter definitions will come in useful sometime.) Bennett is of course a very good writer, so he might be expected to do a very good job of anything he set his mind to.

It might also have helped that the spy genre had already entered the realm of serious literature through John Le Carré and others (Joseph Conrad before him, of course). My knowledge of spies and screenplays is limited so this is more a hunch than a thesis, but it seems likely that there is a trajectory whereby the material of fairly crude strip cartoon narrative (the Fleming books and films were already popular and were in fact in cartoon strip form) begins to attract a literary readership, one with memories of Wilkie Collins and Conrad, as well as of the yarns of John Buchan, that is interested in the complexities of individual motivation and the subtleties of social and political relations and so develops a literary hinterland. In other words the imagination lives in a furnished room.

The Cold War was the perfect terrain for this. It might also have helped that the central characters of such stories involved the wealthier, educated class - the Cambridge Five, for example - people like the writers themselves, characters who in real life inhabited a literary ambience.

So there was glamour, documentary evidence, cultural empathy and a growing body of serious literature.

It's not the same with sport, especially not with football. Football was played by working class oiks who were yanked from a socially inferior low-wage sphere and, later, after the abolishing of the maximum wage, deposited in the world of cash, bling and celebrity. The David Beckham-Posh Spice wedding was the epitome of the latter with its purple robes and thrones. Universally dismissed as the last word in vulgarity it was defended, rightly in the cultural circumstances, or so I think, by Julie Burchill who pointed out that working class people did not aspire to be middle class, they aspired to be rich. The wedding wasn't, in effect, the embodiment of poverty of feeling: the ceremony had meaning for those involved because its form was invested with emotionally charged deep symbols.

It is a complicated argument but one worth pursuing. Furthermore, if there was a blatant lack of culture, or insensitivity to what is considered culture, it might to a great degree have been the product of the cultural relativism of the 70's and 80's, where all accepted cultural canons became objects of distrust and revision. Why would a plumber want to read E M Forster? Why is E M Forster 'better' than 'Eastenders'? Shouldn't the working class develop its own culture of beer and plonk, or so argued the, in some cases, vintage-sipping intelligentsia. This is to put it crudely but these debates are far from over.

*

Bobby Charlton is quite a different matter. He wasn't the subject of the TV Drama: he was its secondary character. The problem was that he was all research, no character, as was everyone else, though you could put up a defence for David Tennant's depiction of Jimmy Murphy. That defence is possible partly because Murphy was far less well known or remembered than Bobby Charlton. The Charlton character looked like Charlton (with a touch of the younger David Beckham): Tennant's Murphy looked nothing like Jimmy Murphy. There was a degree of separation. But then Jimmy Murphy had been dead a long time.

To the play's credit it refrained from patronising its subject by presenting it through the soft nostalgic haze of the Hovis effect. Nor was it burdened by a bullying agit-prop agenda. It had respect, perhaps too much of it. What it lacked might have been a literary milieu such as spy stories, or crime fiction have developed: the furnished room of the imagination. There was no substantial hoard of resonant language available to it; it could only offer the inert stuff of research from secondary sources: speech that had been processed into plain, inoffensive information. The visual direction was strong, a touch heavy at times, but it had wit and invention. The words simply couldn't live up to it.

Charlton the man, the subject of the documentary yesterday, was far more substantial. In him the clichés - decent, shy, modest, emotional and good natured - were fleshed out and given substance. A decent man is not a cliché: he is one of the most valuable and monumental figures in life. I have been lucky to know more than my fair share. Charlton's brothers too were men of that ilk. It was just that Charlton was also a genius of sorts, his heroism on the pitch in tune with his lower-key heroism off it. He himself hero-worshipped Duncan Edwards and could hardly bear himself being spoken of in the same breath. (Compare Balotelli proclaiming himself the finest footballer alive, after Messi).

Charlton the TV character was no figure at all: not a full human being on the one hand, not even a useful Everyman / Everyboy for the purpose of myth on the other. It wasn't the actor's fault. It wasn't even docudrama's fault, not as such. It was partly that the docudrama in this case was precipitate; that it had ideas-about-the-thing, but not the language-of-the-thing. But it might have been an interesting first step in establishing that language.

Thursday, 28 April 2011

One Line on Bobby Charlton (for now)

I watched the programme on him and was far more moved by it than by anything in the play, United. He was not a character in a play: he was a man in a life. And what do I learn from this? [Thinks till tomorrow].

The Best of All Possible Worlds

Via Engage, via Harry Place

The Best of All Possible Worlds

The best of all possible worlds is asleep

having turned in for the night.

It is dreaming of snow a mile deep.

The best of all possible worlds contemplates

its own reflection in the mirror,

its eyes two enormous plates.

The best of all possible worlds is at the bus stop

in a steady shower of rain

watching water fall, drop by drop.

The best of all possible worlds is tired

of waiting for the promised improvements.

It has run out of things to be desired.

The best of all possible worlds becomes

a nervous, clumsy abstraction

all fingers and thumbs.

The best of all possible worlds is a dark star

in a universe of its own making,

muttering: things are fine as they are.

Things are fine as they are, says the sun on the wall

Things are fine as they are, says the cold in the bones

Things are fine as they are in the best of all possible worlds.

It is sunny. It is Thursday. There is a light wind. This too is a possible world.

Wednesday, 27 April 2011

More János Vitéz and... Felix Lajko on zither + Magdolna Ruzsa

Magdolna Rúzsa - Felix Lajko - Még azt mondják (folk song)

Lajkó is playing the zither like nobody's business. Thanks to cousin Mihály Ráday who sent this in an email tonight. It will do as accompaniment to the next episode of my very unfinished translation of Petőfi's János Vitéz

4.

It is late by this time and the brook is a mirror

Where stars in their thousands fitfully glimmer:

Could this be her yard where the water is twinkling?

But how did he get here? He hasn’t an inkling.

He takes out his reedpipe and tries a few phrases

From the saddest of tunes that meanders and grazes.

The dew in the grass is silently creeping

Down the dark stalks as if heaven were weeping.

The porch is the place in the high heat of summer

Where Helen is nestled and swept up in slumber,

But, light and familiar, the melody catches

And brings her to John where he whistles and watches.

She’s barely awake yet, but straightaway hurries

Down to her lover who knows how she worries.

‘How pale you are, Johnny. What ails you, my only one?

The moon on the wane looks no sadder or woebegone.’

‘Reason enough, sweet, for pallour, not knowing

When we can meet again, nor where I’m going...’

‘Don’t talk so dear Johnny, for heaven’s sake spare me,

Stop moping like that or you really will scare me.’

‘My springtime, my blossom, no more will I meet you,

No more will my pipe sing its heart out to greet you.

No more can I hold you, no more may I kiss you,

I leave now for ever, for ever to miss you!’

Venting his grief thus, in words fit to melt her,

Johnny collapses and looks to takes shelter

In fair Helen’s bosom, desperately trying

To hide from his sweetheart the fact that he’s crying.

‘My darling sweet Helen, it’s time that I started.

God bless you, remember me once we have parted.

If you see a dried stalk chased by high winds recall me,

Your fugitive lover, whatever befall me....”

*

And last night's 2-0 win against Schalke was glorious. Highlights tonight at 10:35.

Tuesday, 26 April 2011

Pure Polysterene

Several years ago I was at a Christmas quiz in which we were asked to recognise certain cut and pasted images (cut out of paper magazines, that is, and pasted on paper): people, places, etc. I was quite good at this sort of thing. One picture was of Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex. I had heard relatively little by the band, maybe saw them once or twice on TV, but I identified her. It wasn't that difficult.

You ought to lose marks for knowing that, a slightly pompous voice remarked. Had my gorge risen another quarter of an inch I would have said something suitably rude but I just shrugged and smiled. I've no idea how I know these things, I said.

And now Poly Styrene, alias Marian Joan Elliot-Said, part-Irish/Scottish, part-Somali is dead at the age of fifty-three. This is from today's Telegraph obituary:

...A woman of mixed race who wore fluorescent thrift-shop outfits and proudly sported dental braces onstage, she refused to conform to conventions of how female performers — punk or otherwise — were expected to appear.

Although her wobbly, discordant shriek and the band’s music fitted the punk template well enough, X-Ray Spex’s colourful image was a refreshing contrast to the nihilism of older colleagues; The Rough Guide to Rock describes them as “a wonderful, shambling, musical mess of rebellion, fashion and fun”...

...In July 1977 a live recording of Oh Bondage Up Yours! appeared on the seminal punk compilation The Roxy London WC2 (Harvest). A tamer version was then issued on Virgin, which promptly dropped the group, but they soon reappeared on EMI, and played their biggest gig ever at the Rock Against Racism Rally in London in April 1978.

In November that year X-Ray Spex released the album Germ Free Adolescents, which suggested an increasing musical sophistication.

I love 'increasing musical sophistication'. I can't imagine that, to twist one of Auden's lines, "Sophistication was what she was after" but let that pass. Poly was bipolar and spent time in hospital after experiencing visions. Sometime after 1996 she was run over by a fire-engine and survived. Eventually she succumbed to breast cancer. Having once been a member of a jazz combo named Steddy Eddy and the Metronomes I have every sympathy with Poly Styrene and X-Ray Spex. There is something wonderfully Beano and Exchange & Mart about it. Sic transit omnia.

Monday, 25 April 2011

United: on the other hand / a postscript

Still from G W Pabst's Kameradschaft (1931)

An excellent point made by commenter, panther, in which she says:

I think perhaps the main problem with the drama is a problem it could not solve, a problem inherent in the story it was exploring : what happened with the Manchester United team WAS tragic, almost unbearably so. It wasn't a complicated story.

There is something so right with that that it goes much deeper than my sense of revulsion at the cliché of the dialogue. In the post below I talked about the writer's capacity - indeed obligation - to electrify cliché. I complained that the writer in this case hadn't done it.

But one can be wrong, not so much in the detail but in the context of the whole. It wasn't a complicated story, says panther, and that is precisely the point. The point is the degree to which life is simplified into myth. This is where poems are better than prose. I am thinking here of Keith Douglas who wrote in 1941:

Remember me when I am dead

and simplify me when I'm dead.

As the processes of earth

strip off the colour and the skin

take the brown hair and blue eye

and leave me simpler than at birth

when hairless I came howling in

as the moon came in the cold sky.

Of my skeleton perhaps

so stripped, a learned man will say

'He was of such a type and intelligence,' no more.

Thus when in a year collapse

particular memories, you may

deduce, from the long pain I bore

the opinions I held, who was my foe

and what I left, even my appearance

but incidents will be no guide.

Time's wrong-way telescope will show

a minute man ten years hence

and by distance simplified.

Through that lens see if I seem

substance or nothing: of the world

deserving mention or charitable oblivion

not by momentary spleen

or love into decision hurled

leisurely arrive at an opinion.

Remember me when I am dead

and simplify me when I'm dead.

Keith Douglas died in 1944 at the age of twenty-four. He'd have been just the age to be playing football and be on the Munich plane. The simplification he talks about is the eliding of small distinctions into the broader form of myth. When people are young they are naturally more aware of myth than of distinctions. Distinctions are what we learn through experience and general unpredictability. The idea of dying young and leaving a beautiful corpse is the very essence of myth. That is why we remember Keats more than we do Wordsworth. There are major exceptions to this: the older versus the younger Yeats, the older versus the younger Titian, the older versus the younger Shakespeare. But the mind yearns to simplify, because it requires broad shapes to judge itself by, and it may be that the great resurgence of energy in age is another myth that we sometimes forget, if only because it is rarer.

In this respect the United film's choice to present the broad, crude simplicity of tragedy in terms of an enacted set of clichés swelling beyond itself, was perfectly appropriate. The electrification of cliché can happen - and it might have happened, I'm still not sure - over the whole film. I steeled myself to watch over the iPlayer and did so. I steeled myself on two counts: first to ignore the incidental heaviness and flatness in favour of the whole (very hard for a poet) and secondly, more personally, to allow someone else's presentation of a myth that I too believe in to intrude into the space of my own imagination. That may have been the harder thing.

In that respect the play had set itself an impossible task, or rather an impossible task for someone who participates in the myth. The standard the participator sets is always going to be too high.

However, I think the writer missed a trick, or even several tricks. The most interesting character there was Harry Gregg, who entered the film like a battering ram and every so often gave the action a hard prod. The balance between Gregg and Charlton was potentially powerful. Charlton's hero worship of Duncan Edwards was another unexplored area. The idea of a young player being almost in love with a senior team mate is complex. Murphy too was very good (credit to Tennant), but again his relationship to Busby remained mysterious and peripheral.

In the end the problem was that it was never clear whose myth was being addressed. Most likely it was the myth of the team. It was perhaps an appeal to the spirit of comradeship and leadership, very much like a war story, or the story of the Blitz. The sporting and the military are very strongly connected. Was Manchester United being held up as the model of male society? Maybe something like that, with all those mysterious loyalties and love? Or was it more the simple tragic ideal of sudden early death? Not quite, not exactly.

And that was, probably, the unsatisfactory part of something that could not help but be unsatisfactory. Maybe the unsatisfactory is the myth, and we have to make the rest up ourselves.

United

I was nine and two months when the Munich air crash happened, a year and two months after we arrived in England. We were living in London, still refugees, still foreigners. I didn't know much about football at the time, knew less about England, and next to nothing about Manchester which was to become my city of the imagination. Not so much a city, more just a stadium with a few imagined streets around it. Imagination need not be supplied with a full set of props: sometimes it is much better without, always providing the possessor of that imagination is aware of the fact. That consciousness may, perhaps, be one of the clear dividing lines between surface fanaticism and depth of feeling, even between madness and reason.

Nevertheless, the truth is you don't need much physical reality for the imagination to populate its greater or lesser terrain. It may even be as Eliot thought: humankind cannot bear too much reality. Having walked over the border into Austria, been accommodated in camps, changing countries and languages, I suppose I had had a little too much reality and none of it seemed quite real anyway. Maybe that was a period of madness. Maybe that is why I can't remember it too precisely.

I am not even sure if it was the crash that registered or what followed. The team that died in the crash hadn't entered my imagination at the time: when it did so it was by way of absence. What registered in May 1958, three months after the disaster, and I can't remember how or why, was that a team bearing the name Manchester United had reached the Cup Final despite the best of the great previous team having just died. The new team got to the Cup Final and lost there to Bolton after the goalkeeper was barged into the net by Nat Lofthouse. The goalkeeper had to leave the pitch and that was the end of it. But the team that had died were so intensely present throughout, precisely because of their absence, that it left a great impression on my childhood mind. It was the ghost team and their living shadows that settled there. They took possession of the terrain, that sacred illuminated space illuminated by whatever answers to desire and loss.

*

Or so I think now. I can't really know. I don't think we had a television at the time of the 1958 Cup Final but we might have just bought our very first one. I don't actually remember watching the game. I had learned English very quickly, top of the English English class at my rough primary school within a year, so I might have read the news of the team in a paper, or maybe heard about it on the radio. Too many 'or's here, but it's the best I can do.

How else to explain it? My father had taken me to a match at the Népstadion in Budapest some years back, and there I faintly remember being struck by the heraldic colours moving across the pitch. One of the teams playing that day was, or so I am convinved, Ujpest Dózsa who played in a sumptuous violet. So a little of the heraldry of the occasion - the significance of massed colours and the wearing of favours - might also have been part of the brew. Once in primary school, my second one, I started playing football myself and was picked for the school eleven, winning a local cup in the process. I now had a working stake in the game, and understood how it felt to play it. I played centre forward for Oliver Goldsmith Primary. I wanted to play for England and was disappointed that I couldn't because I wasn't born in England.

I knew someone who was though. Once we had a television I watched black and white football with dad, and immediately noticed the blond haired Bobby Charlton, who was, I understood, a survivor of the crash. Charlton was boyishly magnificent. He strode and swerved and struck the ball so hard it made the net bulge. He drifted past opponents with the slightest swerve of his body. He was the blond hero who was so utterly unlike me that he immediately occupied the commanding space on my imaginary terrain. Manchester United were definitely going to be my team.

That would have been 1959 and United were about to undergo a dip in quality and performance. In 1962 I went with dad to Craven Cottage to watch Manchester United play Fulham. I think Fulham won despite Bobby Charlton. I asked dad afterwards if he thought United would be relegated? Seeing me on the point of tears, he reassured me that it wouldn't happen. It didn't. Only just though. United finished 19th that year out of 22.

So my glory-hunting days began with a disaster, a lost glory, a significant absence, and a sense of sinking, with only Bobby Charlton remaining to save the world. To put this into an Easter framework, if Munich was Good Friday, anything between 1958 and 1964 was the time in the tomb. It was only after 1964 that the Resurrection flickered into being.

*

And maybe that is why the BBC chose Easter Sunday to broadcast United, the first drama based on the Munich disaster. It was, of course, drama not documentary so all the survivors' surviving relatives' complaints that the actor playing Matt Busby was wearing the wrong hat, or that Jimmy Murphy never spoke like that, or that Mark Jones (or was it Eddie Colman) certainly never smoked a pipe in the tunnel before a game, or that some members of the team or backroom staff were never mentioned were, sadly for them, beside the point.

But then what was the point? It made sense to concentrate on three figures: Busby, Murphy and Bobby Charlton, with Charlton as the juvenile lead. It was never going to be a Cecil B. De Mille epic with Eric Cantona in a cameo role. The opening shot was lovely. The boy who played Charlton looked genuinely like a cross between Charlton and an early David Beckham, but was probably a touch more gormless than either at that age. Busby was played as a self-confident private eye from the mean streets of slightly gentrified Glasgow and David Tennant's eyes bulged quite as well as his jaws worked as a taller and slimmer version of Jimmy Murphy.

All well and good, but what was the point of trite dialogue that was far less mature than my nine year old imagination imagined back in 1959? My childhood imagination had cellars and attics, great corridors, terrifying sound effects and plenty of shady rooms. This was written in the dull parlour of stock pieties. It was costume drama written for costumes. I sat through twenty minutes of it, my ears curling in embarrassment at info-dialogue interspersed with mediocre truisms. Even when people speak in truisms (as the Jimmy Murphy character seldom failed to do) it does not strike them as truism: it strikes them as life, and it's life we want not second-hand shagged out truism. The secret languages of the imagination turn the trite into electricity. The task of the playwright is to be the conductor of that electricity. Pinter could do it. Beckett could certainly do it. United? As much electricity as a stuffed eel. Where is Frank Cottrell Boyce when you need him? Probably watching Liverpool.

None of this was the actors' fault. Gormless Bobby was a touch too gormless. David Tennant was working a bit too hard to kick clichés into life. Sir Matt Busby looked pretty good, the Sam Spade of Manchester, but little beyond that. The rest of the team was like a pack of cigarette cards.

Oh reader, I confess I turned off after twenty minutes, unable to bear any more. If anyone wishes to write to correct my rather damning impression you have a few more days while the thing is on iPlayer to do it. Perhaps it all got a lot better once they were dead. But that would be a rather too much like the real life of the imagination.

Sunday, 24 April 2011

Sunday music is... Tamás Cseh, I was born in Hungary

Tamás Cheh (1943-2009)

For L and G, dear friends in Hungary. There is a little anecdote before the song starts

Anecdote

Antoine and Désiré sit down in the great hall at the Eastern terminal at a table near an old drunk with a glass in his hand. There's a singer singing an ancient old tango on a raised stage and Antoine leans over and says to Désiré, See how much they drink, these old guys. Let's see if we can have some fun at the older generation's expense, and in the same movement he pushes the old guy and says to him, Don't you think it's a bit much, always sitting here and getting drunk? How old are you? Two hundred? Isn't it a bit much, surviving everything? Antoine briefly parodies the clichés of old men who boast of living through wars and are full of racy stories.

Song

The old man grins back then the song begins, which is about being born in Hungary, and being seventy-seven, growing confused between how many measures of drinks he has put down and how many political regimes he has survived. He has in fact lived through two wars. He sings of having left thirty-nine women and of being left by the same number. He talks of sheltering and of eating horse-flesh and yet surviving. There is, he sings, an alarm clock in is head and that at he was indeed a soldier though his legs are ruined. He tells how his son has turned out a neurotic, unable to bear the many changes, and when he looks at his grandson he reckons hims a weakling. How could they be survivors? he wonders. He questions whether anyone will speak Hungarian at all in a hundred years time. And when I look at you two (he sings) you don't look too hard either. One puff of wind will blow you away. And what will become of you then? He returns to the alarm clock theme and stresses that though he was once a soldier, and though his legs have gone, he survives and stands before them now.

The anecdote concludes with the old man getting up and leaving.

*

So, what to make of this? Cheh was enormously popular, Hungary's singing bard, full of charm, dry wit, melancholy, lyrical grace, and wry observation. The old man, who is the subject of this song, may be a little drunk and sententious, but there is enough self-deprecation and wit in Cseh's performance to defuse the subject's potential self-pity. After all, the times have, as he says, made him hard rather than soft, unlike the younger generations. And real history is the platform he stands on.

I will find more Cseh at some time. I haven't the time to render the song lyrics as verse. I think Cseh represents the better, more admirable aspect of Hungary - and I don't think that aspect is gone. A little in abeyance for now.

Saturday, 23 April 2011

Notes towards Notes on Photography: Memento and Voluptuousness

Walker Evans: Untitled

Art on the walls: the picturesque. The American photographer Walker Evans had shown us such small comforts as evidence of the essential: the memento mori within memento mori. Here too we find the comforts of art. In one of my favourite Partyka interiors (see photo 5 here) we see two men at work in a shed. Two men in a shed, working men of a certain age, working. The comforts of art are evident in the calendar and pin-ups on the wall. They are images of women, lithe, full bosomed, smooth, soft, young, teasingly unattainable, yet sad, and oddly dignified. They offer a welcome, perhaps even necessary, voluptuousness in a place of spikes and racks and splinters. They are a secret corner of the imagination that would never be on show in the sitting room or the kitchen, the cheap fertility goddesses of desire without ambition. And beneath them, framed and carefully propped, the popular reproduction of J. H. Lynch’s ‘Tina’ the dusky maiden who has haunted a million such spaces and has even filtered into respectable terraced houses as a pin-up refined into low art.

J H Lynch, 'Tina'

Lynch painted the same woman time and again under many different titles, with many different names, as ‘Nymph’ (1969), as ‘Autumn Leaves’, as ‘Rose’, as ‘Tara’, as ‘Woodland Goddess’, as ‘Maria’, as ‘Ladoncella’ and as ‘Evening Farewell’. It is J.H. Lynch’s version of Goethe’s Das Ewig-Weibliche, the eternal feminine that draws us on. Plump as rain, as the round red sun, She cheers us and saddens us. But all is not sex here. Over to one side hangs a sober print in a sober frame, an urban river view, an engraving or etching that opens the shed onto prospects unvisited. Any human life is several worlds, most of which worlds remain hidden and unarticulated. The photographed are not merely points in a composition or points in the viewer’s consciousness. Their dimensions are their own.

Photographs both preserve and interpret. Partyka's preferred light is often the violet hour, the symbolic light that speaks of fading. It is dusk and it is misty. Fields vanish into the distance: the furrows of the land, the rows of cabbage and beet are almost swallowed in the encroaching darkness. There is quite a lot of darkness generally, if not as dusk then as shadow or curtained or closed space. He has a palette too, as an artist does: sodden green and blue-grey edging on purple and violet, earth browns and pale yellows. There is the occasional deep and intense blue, the late summer days of harvest: the mid- and late spring days. There is the burst of yellow in the form of wheat or apples, an old door, the sunlight burning up an interior wall. And there is that powerful insistent red in a boiler suit, a tractor hub, a turkey’s neck, a watering can, an article of clothing and, deeper darker, the deep sodden red of an old wall, rhyming with all the sodden green and the other reds.

Then there are the compositions with their painterly ancestors: Van Gogh, Millet, the Soviet poster, the Caraveggiesque movement into and out of shadow. There are hints of Corot and Breughel. There is the century and a half of photography and the century or so of cinema. The idea of composition is transmitted and modified. Just as my mother posed us in post-classical states of dignified repose or formal alertness, so Partyka requires his subjects to pose for him according to his own vocabulary of visual codes. The subjects don’t pose as such, but they are selected, chosen and edited, on principles of position and composition. So, for example, in terms of colour and form we discover repetition, or what we might refer to as rhyme: a red here answers to the call of another red in the same picture, one strong colour is supported by a chorus of quieter, more subdued ones. The carrots in the hand of the man with the kitten at his feet, the windfall in the grassy yard, the blue boiler suit half-rhymes with the brighter sky behind it. So curve follows curve and vertical calls to vertical. A series of V shaped pullovers unites the farmers at the auction. The twisted and sagging barbed wire matches the twisted and sagging body of the dead fox. Big monumental forms are supported by stretches of calm.

None of this is surprising except that the profusion of the world does not provide us with composition. Composition is what we bring to it. We seek organisation and turn it into interpretation. Organisation exists, of course: the inscape and instress Gerald Manley Hopkins perceived in natural structure; the organisation of petals, of symmetries, of molecules – the physical laws of the universe; of our own bodies - is a given. But organisation has to be perceived, and in perceiving we interpret.

Friday, 22 April 2011

Thursday-Friday, Kiss to Karinthy

Interior of upper level, New York Cafe, Budapest,

There wasn't time for the internet light shop this morning. Packing, tidying, the handing over of the keys.

On Thursday we took the opportunity to walk a little around some of the VII district streets that used to be neglected but now look spruce and positively expensive, but for the fact that property prices are depressed. The VII district is the old Jewish ghetto - it is where I was born and grew up. Király utca, where we were staying is the edge of the VIth and VIIth. On the way back we buy a little gift for Marlie and stop for an iced tea at the New York Cafe, as above, a fin-de-siecle piece of post-rococo, pre-Hollywood extravanganza where writers used to meet, where even in the 1980s and 90s the editorial team of the literary magazine, 2000, made a show of meeting there. (I must put up the photo taken when I visited them and appear to be part of the company). It used to be full of pictures of the late 19th and early 20th century writers-customers but the pictures are gone. It's a little like being in Louis Armstrong's bathroom - I am going by descriptions of said bathroom some time ago.

At a little past 1pm, Judit K calls. It is her book I am currently translating, The Summer of My Father's Death, an excellent memoir, yet much more than a memoir. Her son Aaron arrives shortly after and we set off to walk to a gallery restaurant in Andrássy út, on the way to Heroes Square. We sit outside and eat in the shade. I know little about Judit apart from what is in the book and that she lives with her husband and two children in Geneva. It turns out she is a researcher and an authority on the arms trade - she goes to armaments factories and gathers information. She is a delicate featured woman of some 5ft height so she takes some of the factories and dealers by surprise. After lunch we walk to the Lukács cukrászda (cukrászda = German Konditorei, a cake shop selling liquor and black coffee. The Lukács is particularly elegant in a New York Café sort of way but on the way out we notice issues of a far right- wing newspaper on display. 'We'll not come back here,' says Judit. C and I walk back to the flat and rest.

In the evening it is our traditional parting dinner with L and K. It is balmy. The restaurant is in the old university district where we lived in 1989. Children are on school holiday and have gathered in front the the Law Faculty. Talk returns to politics. The ultra nationalist view of Hungarians as a noble race descended from the Parthians, in effect a nation of bold princes, dependent on no one but themselves, hating Europe, blaming the Habsburgs for spreading lies about the language's Finno-Ugric origins, which are, of course, all lies. They must have old Hungary back (that is the Hungary of the Habsburgs as it happens), including much of Transylvania, Croatia, Slovakia, etc. Many cars carry the map of Greater Hungary. Foreigners, Gypsies and Jews don't fit into this picture, but then they never do.

Except, it turns out, in the early 19th century of Liszt's time, when the gypsies were considered part of nationalist nation-building.

I have a bad night again. The next morning, after packing, I take a book from the shelf, Ferenc Karinthy's Budapest Autumn, which is a fictionalised memoir of the 1956 rising. I picked this up because I had translated his dystopian novel, Metropole (Epepe in Hungarian). Extraodinary as it seems I immediately recognise the first part of Budapest Autumn as the later part of Metropole, action for action, character for character, perhaps even sentence for sentence. It seems he lifted his own fictionalised memory from one book and simply copied it into another.

And then we're out of there, and back here. Maybe some reflections on the experience tomorrow, and a return to the photographic theme.

Thursday, 21 April 2011

Same chair, same internet place, Thursday

Each day it grows warmer by a degree or two so we may be up to 25c today. I slept very badly on Tuesday night so after posting I went home - about half a mile up the road - and fell asleep. We walked out for lunch, then, on the way to the Liszt exhibition (in the grand Ethnographic Museum opposite Parliament) we decided to stop off to call on the poet, Peter K, whose flat lies along the way just by the Danube Embankment. Peter is a diminutive figure of strong opinions on which account we hadn't seen him for some ten years, probably much longer. These are silly things, but maybe we were getting on each other's nerves just sufficiently. But that was a long time ago and C prompted so we rang the bell. I was very pleased we did, though it was a sad time for Peter as his mother had just died a few days ago. She had been a writer of children's books and lived in the next block. We had met her a few times in the eighties and even spent some time with them, and Peter's father, at their place on the Danube Bend at Nagymaros.

Peter was naturally very upset. He had been close to his mother. His girl friend Vali was out. But we sat down in the chairs we had sat in fifteen or more years ago. Nothing had changed. Clear lines, clean and crisp, with Peter's own small paintings and drawings on the wall, the Danube behind us. We talked families, showed snapshots. He was interested in the children's lives. He has no brothers or sisters so is alone now, in terms of family.

We talked art and writing - our various states of affairs - and some politics, though only a little since he didn't want to upset himself more than he already was. He gives us his big Selected and the English language volume translated by Michael Blumenthal. Then we had to go as he had his mother's flat to deal with.

On to the Liszt exhibition which, frankly, is not much of a show, mostly informative posters and a few paintings with one or two musical instruments. The building is magnificent though and people are clearly preparing for a big EU Presidential banquet and conference. Nevertheless the catalogue is useful from the BBC programme point of view so I buy one and am reading it on and off.

Home again by superfast trolleybus. Public transport is outstanding in Budapest from almost anywhere to anywhere.

After a rest and some reading we go out on our free evening for supper, returning to the place L and K took us to, Petri's old haunt, M. We are given a tabler in a nook, and seeing how the tablecloths are made of rapidly changeable brown paper we start drawing on it. I do a drawing and C does a drawing, then we do a joint one. I write two short improvised verses for the drawings. The waitresses don't mind. At least they say they don't mind. The meal is a little heavier than we had intended, but then that is how things often turn out in Hungary.

Today, lunch with Judit K, whose book I am currently translating, the evening with L and K again.

Tomorrow we go home. I'll probably spend another half an hour here in the morning, if time permits, otherwise from my own desk.

Wednesday, 20 April 2011

Same place, different time

Walk around yesterday morning. The place still breaks my heart, it is so beautfiul in its less-than-pretty / more-than-pretty way. We walk past three synagogues, one in the same externally restored but internally abandoned condition, boarded up, the stones bright. Every street corner is exciting. Even the old torn posters and graffiti - mostly inoffensive - carry an energy. I get used to seeing Hungarian faces again, from the refined to the brutal, from the beautiful and young to the worn. We have an omelette for lunch at a cafe called Mozaik. Small and friendly with a lot of books on Budapest. Then we get on a tram and visit my adoptive father-in-Hungary, the marvellous Miklós Vajda, editor, translator, playwright and the author of a wonderful memoir of his mother. Miklós is part aristocrat, and solid gentleman. He is in his eighties now and has restricted movement. His face is a country in itself, much the best aspect of the country: intelligent and courteous and somehow gallant. I first met him in 1984. He is the man who started me translating. We talk books and politics and children and grandchildren. We spend an hour and a half or so before returning to the flat, which is enormous and bare and full of light. I could get lost in it.

Then in the evening to my adoptive brother-in-Hungary, Laci, whose 64th birthday it is. When we first met in 1984 I was thirty-five and he was thirty-seven, just about this time of year. Laci and his wife Gabi are probably the closes people to us anywhere, and it is their friendship that, more than anythinhg, has brought us here now. We eat at a nerarby restaurant, together with their grown children Dani and Linda, Linda's husband András and baby Emma. The restaurant, and Linda's flat, is in a good street. Just udner the flat a bookshop displaying Laci's latest translation, of Endquist, and next door to it, a bar that has become a meeting place for the liberals of the district, including there, we see, Feri Takács, great Joyce expert and occasional actor. Then iot1s in for cake and drinks and talk.

We catch a late trolley bus home. On the way there a young man tried to pick C's bag. Someone else saw it and warned her by tapping her. The man quickly moved down the caírriage. The underpass nearby is missing lights. Today to see the Lisyt exhibition.

Tuesday, 19 April 2011

From the same cafe 2

I come here to deal with emails. The day sunny and promised to remain so. It's a rather sweet little shop, chatty and good natured with its customers who drop in to buy lightbulbs and printing cartridges, chiefly older people so far. A different girl behind the counter today, very blonde and a little chubby, laughing in the next room with an old woman.

I forget how wonderful Budapest streets are, or rather, I do not forget but they strike me afresh each time, particularly after a year's break. Those stern faced facades, breaking a little, as far as they dare, towards pleasure, and in many cases into shameless voluptuousness ring bells very far down with me. I can practically smell them.

Yesterday we were walkinmg with L and G to a restaurant and L stopped and pointed to a particular corner of the Liszt Academy and said, 'There is where that childhood photograph of you was taken. I recognized the stones.' The restaurant was in the street I lived in as a child, almost opposite our block. Further down the street is the Fészek Club (The Nest)which was the writers' union club. We ate there a few times in 1989, with the marvellous novelist, Iván Mándy, who, like most of the major writers of the post-war period was to die in the next two or three years. A handsome old gallant. And nearby there is the spot where the New York photographer Sylvia Plachy took the photo of her old employer, André Kertész, standing by the streetsign that bears his name, though he was not the Kertész after whom it was named. (In the same way there is a Szirtes utca in the city, that is nothing to do with us.)

To add to the redolence, the restaurant, M, is one frequented by the poet György Petri, and named after the woman he loved in the poem named for her (she being the wife of another friend of ours, though we met them both much later, after they were divorced.) It is partly the incestuous nature of the city that is so dense with atmosphere. And here in the restaurant are photographs of Petri by the table where he used to sit, and various beermats with writing on them, some possibly by Petri, some by other writers. Brendan Kennelly has a cafe in Dublin that honours him in the same way. So writers become shrines.

But the Liszt exhibition is closed today and we will have to wait till tomorrow.

The radio has a long set of conversations about the new constitution that looks likely to yank Hungary out of the fully democratic sphere. More thoughts on that another time. And more on photography once we get back.

Monday, 18 April 2011

From a Budapest Internet Cafe 1

It costs a fortune to be linked up from my laptop so this from a clanky Internet cafe in Király utca, the poorer end. Sunny but the shops indicate hard times - several second hand clothes shops (English standard, they mostly declare by way of enticement, so we still count for something in the worlds of used shirts). 30p for half an hour at the Internet is a luxury. The street also boasts a sex shop and a strip club. Life steams ahead in the ex-comecon islands, as György Petri once had it. Otherwise it is inner city Budapest as I know and love it. In fact we are just a few streets down from where we lived up to 1956.

Our flat is lovely and vast and old and one hundred years old. It belongs to dear friends L and G, with whom we dine tonight.

Tomorrow to Liszt.

Sunday, 17 April 2011

Notes towards Notes on Photography: Elegy

Photograph by Justin Partyka

East Anglia is a curious part of Britain in that it was once the richest region of the country, the centre of the wool trade, the point of exchange between Flanders and Britain, its great churches, with their magnificent hammerbeam figures, their fantastical sculpture in the form of misericord and boss, its profusion of churches, bearing witness to the wealth once accumulated here. Norwich was Britain’s second city.

Then came the Industrial Revolution and East Anglia withdrew into its own form of the dark backward and abysm of time. The farmers and the great landowners took all-but-sole possession while tin, steel, coal, cotton and ships prospered elsewhere, breeding a new industrial landscape. It was as if the whole region were caught in amber. Although Ronald Blythe’s Akenfield appeared in 1969, the intervening years have seen lives changed in degree but not always in kind. The shops, the post, the work on the land continue. The wartime aerodromes stand like ghosts in the distant fields. It is as if there were three Norfolks: the Norfolk of the professionals, including academics, artists, doctors and lawyers; the Norfolk of tradesmen, insurance offices and new light industries; and the Norfolk of the relatively unchanged engagement with land and sky. But for the small farmers working under that sky there is a sense of things ending.

Endings are sometimes followed by elegies. Elegy is a sophisticated, highly developed artistic mode that offers the past a shape. That shape hints of grace. Knowing we are watching something in its last phase, sensing it is about to die, is an elegiac feeling. It is as if we had seen everything that preceded it, watched its own life cycle and could now, in some way, apprehend the form that such a passage took. We have sometimes to be careful that elegy does not become rhetorical excess. It is not yet time for the eulogy that concentrates on the subject. It does not have quite that sense of occasion. It is a feeling rather than an address.

With photographs we get both evidence and elegy, both record and interpretation, but evidence and record lie at the core. The figure taking the photograph, the elegising presence, is absent for the key instant when light is just light and film is just a surface: the instant is simply what is, not what is said about it. Great photographs, even just good photographs, are far more than evidence and record but would be nothing without assurance of evidence and record.

The people recorded and presented by Justin Partyka are working the land. They are small farmers surviving in a context of larger scale industrial production. They achieve a bare sufficiency, if that. Their produce enters markets beyond their control. All they control is what lies, literally, to hand: soil, creature, seed and crop, and the relatively simple machines required to make the best of these things. They do not control their conditions, whether those be conditions of price or weather or light or time. Partyka’s photographs of them consist of four elements: soil, sky, yard and interior. People, creatures and machines work the soil, are poised against the sky, cross yards and relax or work in interiors.

The soil is the point. The sky matters in so far as it nourishes or starves the soil. It creates conditions for both soil and human life. The soil itself is worked-through history. It is a palimpsest that has been scraped away and written over time and time again, the tilling and sowing like writing: in the case of these small farmers it is the lives of the writers that is being written. Nor are the yards and interiors of a different substance. Whatever is out there is brought in, life dragged over the threshold into a bare room with its minor comforts, which, in the case of the farmers are generally the comforts of the old: a worn settee, an old armchair, table and simple bed. It’s much like Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters had left it, with the addition of a television or a phone, and a reproduction, cheap print or family photograph on the papered wall. It is subsistence country much as it had always been, not just in Norfolk or England, but almost anywhere in Europe.

*

Tomorrow to Hungary till the end of the week. I may be able to post from there. Internet Cafes beckon.

Sunday night has to be... Stoke City

And therefore Delilah, which can't, alas, be embedded.

For Billy and Stephen. But to win 5-0 in a Cup semi final is more than extraordinary, it is practically supernatural.

My football memory is quite long, and the teams of Tony Waddington's Stoke in the 70s have left a certain imprint on my memory, though I am bound to mix up the eras a little. Let me see now: Dennis Viollet, Alan Hudson, Jimmy Greenhoff, Jimmy McIlroy, George Eastham, Terry Conroy, Mike Pejic, Alan Durban, and ah, yes, Gordon Banks. That is in no particular order. Waddington was the Autolycus of the decade snapping up considerable number of unconsidered trifles.

Do I support Stoke? No, of course not. But on Cup Final day I will. Blue Moon to stay blue.

Saturday, 16 April 2011

Little Birds - English surrealism

This is just a notelet, sparked by thinking about translations of Lorca into English (no specific translation). English is full of clutter that you cannot really avoid - conjunctions, prepositions, definite and indefinite articles - all of which isolate the verb and noun, particularly the poor helpless noun that is exposed as prey to a hard-fisted literal reading. Eventually the noun grows tough and develops a defiant resilience. The Surrealists' notion ofThe Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella is cursed by the distinct and separate entities that refuse to melt into much more than Lewis Carroll's happy dream in:

...Little Birds are bathing

Crocodiles in cream,

Like a happy dream:

Like, but not so lasting -

Crocodiles, when fasting,

Are not all they seem!

Little Birds are choking

Baronets with bun,

Taught to fire a gun:

Taught, I say, to splinter

Salmon in the winter -

Merely for the fun.

Little Birds are hiding

Crimes in carpet-bags,

Blessed by happy stags:

Blessed, I say, though beaten -

Since our friends are eaten

When the memory flags...

(from 'Little Birds')

I do love Lewis Carroll, and Edward Lear too. They are England's true surrealists. Myles na gCopaleen used to do those odd surreal lines for a lark, producing them out of the hat of his imagination as a parody of 'significance', but then he was as Irish as (being himself) Flann O'Brien, and the Irish take on surrealism is generally more jaunty.

Of course, crocodiles bathed in cream, baronets choked with buns, splintering salmon, and stags blessing carpet-bags are strange, violent excursions into what is almost Jan Svankmajer territory. Not in the context of the whole poem though. The whole poem works more on the energies of social solecism rather than of revolutionary manifesto which may be why David Gascoyne's surreal poems have always felt a little laboured to me.

There is something jowly and pugnacious about English, however you sing it, however Keatsian you get with your vowels and sensory delights. It will not easily relinquish its empiricism. I am tempted to take Tom Paulin's criticism of Tennyson as 'velvet on a tin tray' (I think my memory is serving me well) as a compliment.

Friday, 15 April 2011

More Notes towards Notes on Photography: On the edge of cliché

Photo by Justin Partyka

In Justin Partyka’s work too we discover a temporal, provisional balance. The objects he photographs clearly exist. You cannot always be sure with contemporary photography now, because technology has made it possible for photographers to invent, graft, cut and rearrange. The photograph has hardly any innocence left in it, or rather the innocence must always be regarded with a certain scepticism, suspected of guilt before proven innocent. Partyka’s fields and farmyards are really there. I think we might proceed on that assumption. In that sense the photographs are reportage and memento mori, forms in front of a machine that is intended, in Isherwood’s terms, to be ‘recording, not thinking’, if only in the instant of time it takes Partyka to press the button. Crowding in on that solitary moment are the vast armies of Isherwood’s ‘thinking’ in the form of decisions regarding subject, light, angle, time and the rest.

And beyond it too, if only because thought is not quite the same as interpretation. Thought could take a decision then let it rest. Interpretation does what my mother did: make choice an aesthetic issue, an issue of style and perception, and desire. Thought is not fully conscious in these processes: the idea of the artist’s intuition or instinct suggests a realm of educated guess, a series of automatic reflexes or gambles that, with a bit of luck, continue to explore ever newer, ever deeper, ever more exotic ground. If it does not explore such ground it lapses into cliché, kitsch, ersatz, or to put it into plain English terms, a received idea, even if the idea is received by the very person who first had it. Art in this sense – and my case is that photography, however special it is or has been, by virtue of its innocence, is an art – is always at the edge of cliché.

But there is another way of putting that. We might propose that art is precisely that which lives on the edge of cliché: that the moment of rawness, the well known ‘shock of the new’, has to borrow its terms from somewhere, even if it only reverses them. Anti-art is anti-something. The marginal, as Howard Jacobson wrote in an article, is marginal to the centre. The central page-text, the art that is status quo ante, is substantial. Elements of it are following the inevitable path to ossification and cliché, but if it were entirely dead there would be no point adding marginalia or reversing it. Art is neighbour to cliché. The marginalia drift ever closer to the centre which is never dead, but has powerful electric currents playing through it. My brother and I sit in a pose that still has life or might be in the process of regaining life. The hand-colouring has thrown us into the exotic margin to which the once common central text of hand-colouring had become assigned. Texts swim in and out of each other, just as our own atoms and electrons move in and out of ambient space.

To be continued

Thursday, 14 April 2011

Neutrinos - what's the point, eh?

The picture above is of Super Kamiokande, a solar and atmospheric neutrino detector in Japan.

Listening to the the blessed Melvyn this morning on In Our Time and he has this wonderful programme about neutrinos, of which I understand about 10% but am spellbound by the other 90%, when it occurs to me that this is not about what an economist like, say, Mr Gradgrind (who was keen on facts and numbers) would regard as utilitarian science. How much is a neutrino worth nowadays? Damn things are so small and useless they don't even have mass! They just slip through the universe - not to mention our bodies - in their billions and fail to do anything at all. Not an ounce of help with the GDP and will do nothing to get the economy moving. What's the point of them?

If there is anything more useless than the arts (I mean apart from the paying customers and tourism) it must be the neutrino. And would you believe it, there are professors in our publicly-funded overpaid universities, who are digging enormous holes and filling them with really expensive chambers just so they can catch a stray neutrino. And what do they do with it when they've get it? You can't sell them. No-one is going to buy a neutrino, not in today's market.

Those scientists in their ivory towers had better get off the public payroll quick. Take their Arts Council grants away. Might as well give them to poets for all the use they are.

ps Not to confused with band of the same name, or the Brazilian footballer Neutrinho.

Neutrinho

Wednesday, 13 April 2011

More notes towards notes on photography: We are exotic

I had begun this introductory essay for Justin Partyka before and now I want to pick it up. Photography is a subject I keep returning to because of its association with truth to evidence. As the end of previous blogpost on the subject read:

...The camera is the eye. The camera is the I. Best believe it.

And so we go on...

But the moment of innocence is minimal. The moment is not sought for innocently, and is not handled innocently, if by innocence we mean without knowledge, calculation, idea, culture or intention. Sit there. Yes, just there. Turn towards me. Smile, Move your hands to your lap. So. Now wait while I move around you. Or, If I move slightly to my right the elements will be better composed. I will lose that awkward shadow, and yes, that Hall’s Distemper Board too. Perhaps I should focus in on the washing line not on that hold-it smile?

Or…?

Or my mother’s occupation in my childhood. Starting as a press-photographer she was soon confined, through illness, to a home-based one-woman light-box laboratory-cum-surgery, a visual plastic surgeon with a shard of lethal-looking razor, removing a wart, or a shadow under the eye from a negative, adding delicacy to a cheekbone, tidying up a loose lock of hair. At times she would even take out those tiny, magical tubes of photo-oils, mix them on a small sheet of glass, and with brushes that were hardly there, colour in what had been black, grey and white, embalming those from whom the colour had vanished, turning them into peculiar mortuary icons, as my brother and I were so turned, introducing our ghosts to the world of the technicolour sarcophagus. That sarcophagus has a beauty of its own now. It was the art of the possible as it looked then, as we looked then, as the colour lay then, as the hand that moved the colour moved then, as the person who was alive at that time, loved the colours then. The beauty was her desire to preserve those in image that she might not have been able to preserve in life.

What were we like then, in those photographs? I think we were a little like those Pompeian wall-paintings or Great War postcards with their tinges of pink and blue against sepia.

And how were the pictures composed? On what principle?

Composed they certainly were, mostly on the principle of balanced form.

And where did she learn these principles of balanced form? In what sense are such feelings innate, or culturally transmitted?

We weren’t being composed according to the principles of Japanese woodcut, or the principles of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism that derived their balance from the Japanese example. Nor were we composed, not exactly, according to the principles of Baroque art, as catalogued by Wölfflin. We weren’t dynamic shapes in motion: we weren’t reportage and speed, we weren’t bursting from dark into light, we weren’t protruding over the picture frame in an act of psychological aggression. No, we were still and posed and sub-classical. We were arranged to be at rest. It was from a position of rest that we turned our heads to regard the world. We were an arrangement for posterity. We were interpreted as form.

The innocent moment of light through lens, on film, remained. It was the chief reason we were, to put it in Barthes’s terms, memento mori irrespective of art. Yes but we were also interpreted. We were not only forms but Form. We were the balance between image and moment, between representation and dumb, once present, self. The latter we cannot lose. The former has since been reinterpreted time and time again, falling into the ambit of cliché, then, as time passed, out of it again, into pure exotica. We were, are, exotic. It is language that makes us so.

To be continued...

Tuesday, 12 April 2011

Launch of Agnes Lehoczky's book on Nemes Nagy

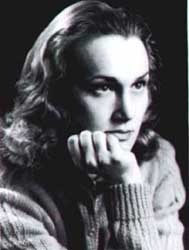

Ágnes Nemes Nagy in youth.

No post yesterday as we had to go down to London early and didn't get back till well past midnight having attended the Hungarian Cultural Centre launch of Ágnes Lehóczky's book, Poetry, the Geometry of the Living Substance about the great Ágnes Nemes Nagy. The book is essentially the critical part of Ági's PhD, and having been one of her supervisors, as well as one of the translators of Nemes Nagy, Ági asked me to write the Foreword. So I was part of the evening too, as was Peter Zollman who had also translated her, some fifty-one poems in a bilingual Hungarian edition.

Peter is not an unsung hero, but a hero whose triumphs might be sung louder. Since retiring from work he has undertaken the translation of great chunks of the Hungarian verse canon, most recently of the poems of György Faludy. He has got better and better as he has gone on, his command of English verse and his ear for English register constantly improving, and a lot of his work is outstanding. We come to translation from opposite ends: he from a deep immersion in Hungarian poetry learning to write English verse, I from English poetry recovering what I can of my original Hungarian, but having to learn everything anew. He firmly believes his end is better, and for all I know he may be right. Having read quite a lot of inferior Hungarian attempts at translation into English I have tended to believe the opposite though. I think Peter is an exception and deserves great credit for it.

But the evening is Ági's. She leads, and talks chiefly about Nemes Nagy's life and the nature of her work: Nemes Nagy's power, resentment, aloofness, courage and stony resolve; about that position between Rilke and Beckett that she craved. It is not a big audience but big enough with some old friends and students, and the HCC do us proud. It turns out that one member of the audience was actually taught by Nemes Nagy when she was a school teacher, and that he never knew she was a poet. She was in fact banned at the time, which was one of the chief causes of her resentment. She refused to comprise then and ever after.

Peter and I talk and read a few translations then it's off to The Maple Leaf opposite where, according to the TV screen Liverpool are beating Manchester City 3-0. That makes it a particularly good night.

Ágnes Lehóczky in youth, in fact very recently.

Today more negotiations on the PBS future and correspondence with Mario Petrucci about Enitharmon as well as a board meeting of the Wymondham Words festival, here in the house.

Sunday, 10 April 2011

Meanwhile in Hungary...

The philosopher Ágnes Heller on the political climate in Hungary.

To say I find the Hungarian situation depressing is putting it mildly. The great pianist András Schiff, who lives in Italy, has been threatened with having both hands cut off if he returns because he wrote an article in which he questioned whether Hungary was fit to be the president of the EU. By way of response, one of the members of the ruling Fidesz party, declared it was a pity that more people like Schiff, Nick Cohen and Daniel Cohn-Bendit, who had expressed similar opinions, couldn't have been massacred in the White Terror following the fall of the Bolshevik revolution in 1919. A little more massacre, if you please, maestro.

Meanwhile the attempt to smear intellectual critics of the regime goes on with accusations of financial impropriety. This has been the charge levelled at, for example Agnes Heller the philosopher, who dared write this. And today's Magyar Hirlap carries news of a demonstration by all of ten members of an organisation called A Szövetség a Német-Magyar Párbeszédért (The Federation for German-Hungarian Dialogue, and one may not have to wonder what element of historical German dialogue they might wish to pursue) protested at the 81 year old internationally recognised philosopher's appearance at a media conference of the paper, Die Tageszeitung. They accuse her of slandering Hungary. It is fascinating to read the comments under the clip: they fully demonstrate their own position while denying it.

How do I know about this insignificant little demonstration? Because the Hungarian paper features it on its web front page, and a lot of blogs and websites have also run with it.

Anti-Semitism? Certainly not! Though Schiff and Heller are in fact Jewish. Heller had criticised the Hungarian public for not speaking out about the current social and political climate.

Well now, there is the Demokratikus Ellenzéki Összefogás (the Alliance of Democratic Opposition), and there was this march of some 50,000 people through Budapest on 15 March. These are causes for some cheer. I cannot quite believe that Hungarians are slipping into fascism, though there are people who wouldn't mind at all. Especially those who'd have liked a more comprehensive massacre in 1919.

Saturday, 9 April 2011

PBS: Carol Ann via Louis MacNeice...

In today's Guardian (link to come):

A CUT BACK

Carol Ann Duffy

It’s no go the LitFest, it’s no go up in Lancaster,

though they’ve built an auditorium (still quite wet, the plaster)

a bar, a bookshop, office space … well, they won’t need wheelchair access.

All we want is a million quid and here’s to the Olympics.

London’s Enitharmon Press was founded in 1967,

but David Gascoyne and Kathleen Raine are writing now in heaven,

with UA Fanthorpe, John Heath-Stubbs; dead good dead poets all.

The only bloody writing now’s the writing on the wall.

It’s no go the national art, it’s no go cake with icing.

All we want are strategic cuts, it’s no go salami slicing.

It’s no go the Poetry Trust, it’s no go in East Suffolk;

Aldeburgh’s east of Stratford East. As Rooney says, oh f-fuck it –

because it’s no go First Collection Prize, it’s no go local writers.

We’ve been asked to pull the plug, the rug, by coalition shysters.

National Association of Writers in Education?

No way, NAWE, children and books, the train’s leaving the station.

It’s no go your poets in schools, it’s no go your cultures.

All we want is squeezed middles and stringent diets for vultures.

It’s no go the pamphlet, the gig in Newcastle no go.

All we want is a context for the National Portfolio.

Three little presses went to market, Flambard, Arc and Salt;

had their throats cut ear to ear and now it’s hard to talk.

They remember Thatcher’s Britain. Clegg-Cameron’s is worse.

Deathbyathousandcuts.co.uk, the least of which is verse.

It’s no go the avant-garde, it’s no go the mainstream.

All we want is a Review Group, chaired, including recommendations.

Stephen Spender thought continually of those who were truly great;

set up the Poetry Book Society with TS Eliot, genius mate.

But it’s no go two thousand strong in the Queen Elizabeth Hall.

Phone a cab for the Nobel laureates as they take their curtain call.

It’s no go, dear PBS. It’s no go, sweet poets.

Sat on your arses for fifty years and never turned a profit.

All we want are bureaucrats, the nods as good as winkers.

And if you’re strapped for cash, go fish, then try the pigging

bankers.

Now that is what a Laureate can be for!

Friday, 8 April 2011

The Guardian podcast: Writing in a Second Language

I did this interview just before going off to India, in fact on the way to the airport. I wondered if I had done it well enough. Finally I have had the courage to listen to it, and it's OK really. There is a very interesting piece about Spanish writing about the Civil War before me, then I come on with Sarah Crown, and I more or less say what I would have said if I had had time to think. But it's all pretty well impromptu, with one or two images that have occurred to me before in this context.

Here is the link.

Thursday, 7 April 2011

L'Affaire Rooney

Wayne Rooney stunned TV viewers with a foul-mouthed rant at TV cameras after scoring a hattrick against West Ham last Saturday (Daily Mail)

Prodded to a football post by a contemptuous one-liner in a comment, I oblige. Having been stunned by Rooney's three word foul-mouthed rant (warning: rant quoted below), today's reading comes from The Book of Rooney, Chapter 25, verses 1 - 6.

1. Wayne Rooney is the middle class person's parody of the working class boy. If he had been no good at football he might have been arrested for bouncing on car bonnets and breaking into vehicles generally. Then he might or might not have found a job, drank a lot and got very fat and died at the age of forty five as a result of his pitiful working class indulgences.

2. Wayne Rooney has taken up the middle class habit of swearing. Swearing is perfectly acceptable on Radio Four comedy and certainly on TV but not by real working class people, especially not when thirty thousand other people are swearing at them. It is because he has taken up this middle class habit that Rooney is now in trouble with the FA which does not stand for what you might think it stands for.

3. Wayne Rooney has had a Bad Year. He has been a Bad Boy. He has been a Bad Husband and a Bad Role Model. He had a Bad World Cup, partly because of a Bad Injury. The rest of the team were also Bad but he was supposed to be Good. So, most unforgivably, there have been times he has been a Bad Footballer. In this respect he is unlike all the other well known people who have had similar troubles but did not appear to be Bad Footballers.

4. Wayne Rooney plays for a team with a manager so Bad he keeps winning things when he shouldn't. Bad People shouldn't win things. Bad People don't talk to Good People when the Good People have accused their relatives of crimes they couldn't prove they had committed. This only annoys the Bad Manager because he is Bad.

5.Wayne Rooney, having had a truly Bad Year was so pleased to have scored a hat trick he let off a lot of Bad Steam by exclaiming: What!? Fucking what!? in the face of a cameraman who had pushed his camera into Rooney's face. This was a gnomic utterance whose object seems at best enigmatic. So enigmatic as to be Bad.

6. So now he is banned by the FA for two games, one of which is against the team's local rivals, Manchester City, whose chairman happens to be the chairman of the FA. This is of course coincidence. This comment is in the form of irony. So is this.

Here endeth the reading.

Much as I love football I sometimes get the feeling that the game is very corrupt indeed. Not because of the Rooney episodes, but because so much money rides on it and because so many decisions seem to be flawed. I sometimes imagine vast amounts of industrial cash flowing in bets, much as with international cricket in the recent Pakistan case. I think of FIFA and EUFA.

Then again I sometimes think the opposite. That the people running such sports are far too incompetent to engage in anything requiring as much intelligence as large scale corruption.

But then I wake up and all is right with the world.

Wednesday, 6 April 2011

The Tyranny of Relevance

The reason I stayed in Sheffield was because of the Leeds Salon continuing debate on the subject of this post. Leeds was coming to Sheffield on Monday night. The discussion was strongly led by David Bowden of The Institute of Ideas, the speakers being Michael Schmidt, Michele Ledda and myself, each of us speaking for some 7 minutes, then launching out on a discussion.

The relevance to what? might be the first question, though by this time I had understood that the subject was really education and the place within it of the arts, particularly poetry. But MS started by talking about the relevance of poetry to public affairs and, inevitably, Auden's line in his In Memoriam W B Yeats poem about poetry making nothing happen, the suggestion being that poetry's relevance was not quite in the public field: the poet does not have a message as such.

My first task then was to be relevant to MS's statement with which I was broadly in agreement while pointing out instances where poetry did make things happen - the revolutionary poets of the nineteenth century, particularly in Europe, and my part of Europe above all. I also mentioned that while Auden said that poetry makes nothing happen, he qualified it by saying it was a way of happening.

Michele kicked us off into the proper subject with a properly considered set of points, chiefly reflecting on various government statements - in fact rather more the last government then this one - on the importance of all school subjects being relevant to jobs, economics, and the needs of industry (citing Estelle Morris, among others. And indeed it is Michael Gove who recently used the term 'the tyranny of relevance' to suggest the importance of traditional subjects, including Latin and so forth. John Carey might have been the very first, thoughy Michael had a claim on it too.