|

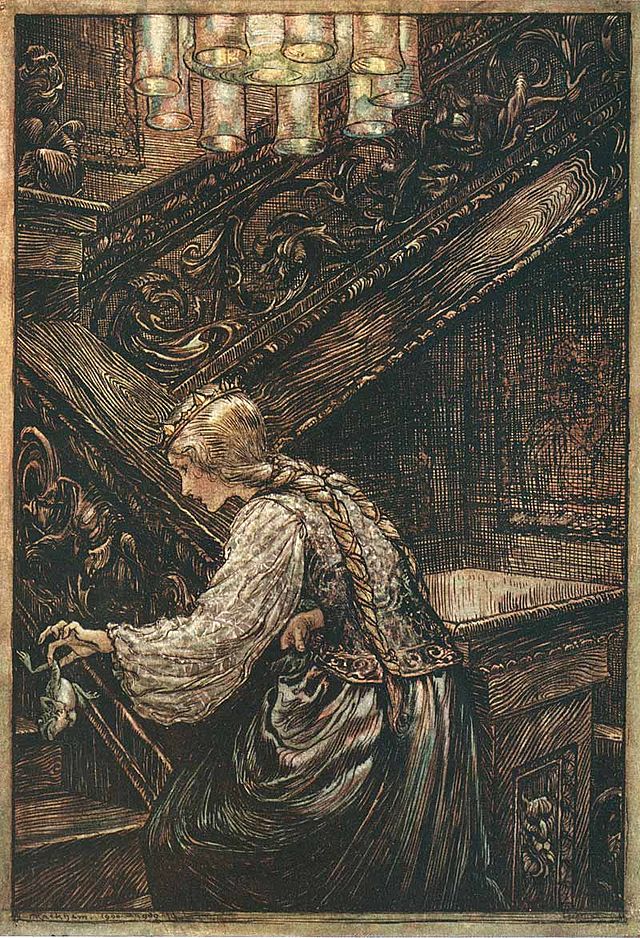

| St Apollonia |

It had been arranged by a Hungarian mathematician friend working at the Science Park that I should spend an hour so on Saturday talking with his Hungarian visitors (the men old schoolmates, the women their wives) about translating from Hungarian. It was to be in Hungarian, a slightly daunting prospect since when it comes to complicated matters I speak better, more precisely, more subtly, in English.

It was the afternoon and hot. There were twelve around the table on the patio and my host was going to act as chair. My answers to his questions tended to the long as usual and, to tell the truth, it wasn't too bad. I could say more or less what I meant only a little more clumsily, but it was not impossible. I couldn't have done it five years ago. The guests were charming, attentive, curious a set of highly qualified professional people, all about six years younger than me. They are part of an important, deeply-cultured layer of society who have lived under two different systems and have carried their culture with them in both.

What they really want to know is how Hungarian literature, which they all love and know, fares in another language. The conversation focuses on a particular few Hungarian authors - both poets and novelists - and they all pay tribute to their literature teacher at school. They can quote, our host above all. He is fascinated by the relationship between maths and poetic metre. The women are quieter - they are professionals too, a couple of teachers, one a graphic designer - but that is not unusual in that generation. It is rather different now.

Then dinner is served, delicious, still

al fresco, and wine is drunk. The sky darkens, the air chills. Some politics is discussed, albeit tentatively, but I gather they are all on the liberal left-of-centre wing of opinion. They don't complain directly, I do however sense a reservoir of anxiety under their comments. I find it easy with them and wonder why this generation of educated, fully civilised people isn't running the country. The fact is it is the equivalent of their younger brothers and sisters - and indeed their children - who are doing so, and they are different, further to the right, sometimes much further.

*

Today to Cromer to read briefly at a literary

lunch organied by Mark, who runs the local Jarrolds. It's a 1pm start and we arrive early so we can park then go for a walk along the top-of-the-cliff level. It's slightly overcast but the light has a fine pearliness especially on the sea. It is faintly intoxicating. Cromer is clearly being smartened up. It is somewhat unique with its Victorian turrets and balconies and its Hotel de Paris. The beach is long. The pier that was damaged by the storm surge is now repaired though the shops on it have not all reopened yet.

When we get to the venue, a large inn, Mark is there to meet us and offer us drinks. Almost immediately

Patrick, author of

Badgerlands, arrives, followed by

Jim Kelly who writes the

detective novels. We are the three speakers due to speak fifteen minutes each between courses. I am to go first with a selection of children's poems from

In the Land of the Giants. Mark's father turns up and we talk about places and times. Mark says it will be mostly women in the audience, though that's no great surprise.

The surprise is walking in and seeing the place filled up, everyone already sitting at tables. It is a capacity audience and not only are they ninety percent women but, at a glance, I would say they are all over sixty. They don't have the air of blue-stockings but they are certainly readers and like a literary occasion. Where are their husbands? They have either departed this life or simply made their excuses. In any case it confirms my frequent observation that wherever a critical number of women are gathered men absent themselves. I won't speculate about why that may be but it is a pretty general truth. (I will speculate on another occasion.)

The audience is omnivorous in literary terms and they clearly enjoy themselves. They clap long and loud and they buy plenty of books at the end. The organisation of the lunch also works. So I do mostly poems full of play and a bit of magic, Patrick talks marvellously at full speed about badgers, about their cruel treatment until 1908 and then, after Kenneth Grahame's

The Wind in the Willows of 1908, the public embrace of them. He illustrates this with lots of nice incidents and addresses the

culling question. We learn, among many other things, that the badger population of the country has in fact increased by 76% in the last - was it ten years? He get more question than Jim and I do, and Jim does a very fine summing up of four of his books, which all involve a

what if question and the idea, even if mostly figuratively, of a

locked room. How could a crime be committed under those circumstances? It turns out both the detectives in his best known novels - an elder and a younger - are based on his father who was a Scotland Yard detective.

A nice format this. Three different kinds of writing and a decent lunch in between with time to let the courses go down. We sign books and drive off in our different directions. Now it is dusk, that most beautiful time of day which seems to roost inside us like a bird homing to its nest.

*

Tomorrow I have four teeth out, my first extractions in decades. They are not front teeth so I will look perfectly normal after (not immediately after, of course). They are mostly broken teeth and this is to prevent infection. I hardly ever suffer from toothache and when I do it is mild. Pray for me

St Apollonia. I think you had a far worse time than I am likely to have, though I'll probably be bedbound and painkillered the rest of the day with no hot or even warm food. Cold soup it is. Cold sorrel soup. Delicious.