|

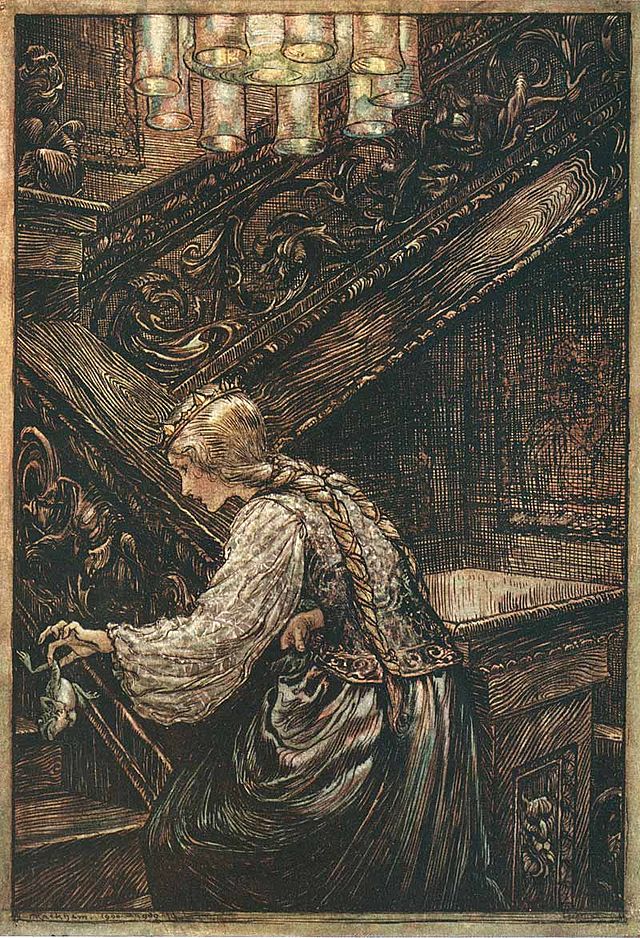

| Arthur Rackham |

It's statistically improbable that pigs should fly,

That aeroplanes should fall out of the sky,

That blackbirds should be baked into a pie.

It's statistically improbable so don't repeat it.

It's not a magic apple when you eat it,

So tell the child's imagination: Beat it!

God bless Richard Dawkins (someone should)

We need a sceptic in the neighbourhood

To block the path to the enchanted wood.

It's not my greatest poem but it's topical, far from difficult, and may even be understood by Jeremy Paxman's notion of 'ordinary people'. It's a response to what the Daily Mail said Richard Dawkins had said, which was not quite the same thing as Richard Dawkins did in fact say. Very little the Daily Mail says people have said is what people actually did say.

In fact Padraig Reidy in Index on Censorship says I said things I didn't say in saying what Jeremy Paxman both did and didn't say. All very sly stuff according to Reidy. I thought I was talking about ideas and poetry, about knowing and not knowing, and the notion of apparent difficulty and only mentioned Paxman once, without any rancour at all, having, after all, been asked by The Guardian to write a response to their own article (the one linked to at the top) in which Paxman is quoted as saying what he actually said, though he had said other things too which the Guardian article I was working from did not have him saying. In other words I was engaging with that thought, right there, about inquisitions, ordinary people and explaining. Are you still with me? Mr Reidy, are you awake?

But back to Dawkins. It seems to me that what Dawkins did actually say (listen to an excerpt here) is not all that different from what the Mail implied he had said. The way The Mail put it orginally was that Dawkins thought that fairy tales were bad for children because the idea of frogs turning into princes was a statistical improbability. Did Dawkins say that? Did he put it that way? In what might be a later version the Mail has him saying that it was:

'pernicious to instil in a child the view that the world is shaped by supernaturalism.'

That's in inverted commas so I am assuming it is what Dawkins did actually say

But since nobody reading this is likely to take the word of the Mail for anything, here is the relevant piece in the Guardian, after the initial Mail story appeared.

Dawkins admitted that he had once questioned whether a "diet of supernatural magic spells might possibly have a detrimental effect on a child's critical thinking."

But he added: "I genuinely don't know the answer to that, and what I repeated at Cheltenham is that I think it is a very interesting question. I actually think there might be a positive benefit in fairy tales for a child's critical thinking ... Do frogs turn into princes? No they don't. But an ordinary fiction story could well be true ... So a child can learn from fairy stories how to judge plausibility."

The frog and prince part is the odd thing. Dawkins is asking the child to read the story in terms of plausibility.

It seems to me that to be talking about fairy tales in terms of plausibility and scepticism is a sign of something skull-splittingly one-dimensional. According to this Dawkins test there is only one kind of truth and that's the one tested by its plausibility.

I am still trying to understand in what sense even 'an ordinary fiction story could well be true'. 'Well be true?' In what sense? In that it actually happened? Or that it should be possible to prove that it could have happened? Fiction is full of implausible coincidences, that is its whole domain. And somehow or other people can tell the difference between it and life, with all its own implausibilities.

Blocking the path to the enchanted wood (or delusional wood as one Dawkinsite Twitter commenter put it to me) is a bit harsh. But I'm doing it for the frogs. Every one a prince!

5 comments:

I typed a lengthy response to this, but then my computer crashed. Suffice to say I enjoyed your response to your response, and your Paxman stuff too.

Dawkins always reminds me of the eldest child in this short piece by Schopenhauer:

"A mother had, for their education and betterment, given her children Aesop's fables to read. Very soon, however, they brought the book back to her, and the eldest, who was very knowing and precocious, said: 'This is not a book for us! It's much too childish and silly. We've got past believing that foxes, wolves and ravens can talk: we're far too grown-up for such nonsense!' - Who cannot see in this hopeful lad the future enlightened Rationalist?"

I love this post. There are two different worlds, the world of the categorical and the world of shape and meaning. The one is sharply analytical; the other gives voice to this, to quote you from a comment on this blog some years ago that I always kept:

"Those moments in a life that is fleeting for us all. But we register them because we are capable of registering them - and they matter deeply. Poems try to join these things to each other and hope to find meaning in them, or at least a shape.

In this way we are joined as human beings - all special, all nothing, but all we really know, guess, sense and make."

Both express truth, but they are different. One is literal, demanding clarity, and that is where I mainly live, which is why, though I have tried, I can only write bad poetry and cannot do fiction. The Dawkins and the Paxmans are only comfortable with the categorical, and though they can enjoy the other world, they desperately want it to conform. It does not and it will not.

We need both; they are complementary. Clear analysis is very useful when young lions appear bearing offensive analogies, but without compassion, humour and tenderness see how little it gives us.

Ribbit!

I'm very grateful for all three comments. One of the great questions William Blake addressed was how far contraries should be reconciled. He argued they shouldn't, believing that it was the conflict between them that produced the energy that he so admired.

Blake was a great great man and writer but, as most of us will know, it's hard to follow him all the way down the road of his conclusions. Or to put it another way, that which Peter calls the categorical is a vital way of dealing with the practicalities of life. You can't eat a metaphor.

The world of shape and meaning, constructed and interim as it is, is however vital in its own way if only because the human mind lives by construction in the awareness of its own interim condition. In that respect it is as true as the categorical (which can, after all, be categorically wrong, its series of readjustments and revolutions being the history of science).

Should we reconcile the contraries of category and meaning? Blake's great NO is the visionary's answer. We are part-time visionaries, most of us. We have to live in the world of categories and cannot cut ourselves free of it. We can't eat our own metaphors.We may even feel there might be something dishonest in claiming to do so.

But we cannot help perceiving the world as metaphor. Frogs and princes assume a different relationship at this level than they do in the physical world. Keeping the two worlds in suspension is vital, and maybe Blake is right after all. We don't need to reconcile them. We just need to recognise them for what they are.

As with Blake, so with Proudhon, whose own anti-utopianism was based on the need to continually find a balance between irresolvable contradictions. This was unlike some of the revolutionaries of his time who sought to create the final resolution.

Good literature is rather good at exploring what Blake and Proudhon saw as inescapable. The edible world is too often desperately seeking certainty.

(Though there are also those that create uncertainty where certainty should be transformed into conviction - post-modernism is their main tool in this case).

Post a Comment