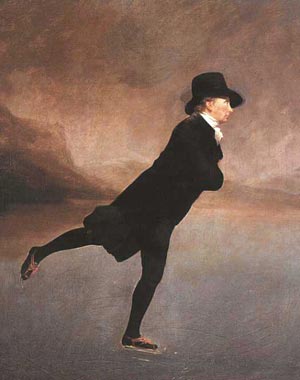

The Vettriano bothered me so I took out this well-known, much-loved painting by Henry Raeburn of The Reverend Robert Walker Skating (1784) for comparison with Vettriano's ice picture below. How do you define the difference? Because the difference is enormous but subtle. It isn't just that Raeburn's figure is in movement rather than statuesquely posing. It isn't just that we see his face while Vettriano's faces are turned away from us. It isn't even just that Raeburn was a wonderful sumptuous wielder of paint whereas Vettriano is glossily workmanlike.

Jonathan Jones wrote a brief sketch of it in The Guardian a while ago. I whisk a paragraph from it off the net here:

There's a wonderful good humour to this painting, whose full title is The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch. A Presbyterian minister in black frock coat, black hat and black stockings; his face is dignified, grave - but with a twinkle of laughter. He is as graceful as a Degas dancer, perfectly balanced, poised on the ice scarred with lines made by previous skaters. The wild landscape behind Walker ought to be bleak, but his self-confidence has turned it into a place of civilisation and sport. This is an optimistic painting, an 18th-century image of reason triumphing over nature. The Reverend Robert Walker has conquered a wasteland - though this icy desert is not remote at all, but just outside Edinburgh, with Arthur's Seat looming up on the left.

Yes, that is true but it is greater, grander, more monumental than that. It's the time of the Scottish Enlightenment. The man has something of the delicacy of eighteenth century late Rococo but with a clear pre-Romantic awareness of the power of nature, of his social position, and of the gravity of his inwardness. His face is solemn and absorbed, his arms speak of self-control but his body flies. He is not simply an amusing paradox involving decorum and wildness, or responsibility and freedom. He is at the tipping point between these polarities, but retains his almost heroic balance. And the ice and the hills rising behind him in the mist speak of something beyond the picturesque, something in which the outside of things is reconciled with the inside. Not just civilisation and sport. Reason doesn't quite triumph over nature, God skates on thin ice.

Paintings, of course, are not the images they depict, or at least no more than partially so. They are material: they are paint applied laboriously or lightly to a surface: colour and tone and weight and modulation. Paintings are built. They are manual labour. The image is what they are building to. Great painters build towards great images. Everything in the Raeburn is built, but you can only build out of some apprehension of image - whether that be figurative or otherwise - pressing towards realisation. In the Raeburn there is not only an extraordinarily substantial image but a sense of it being assembled, striven towards, being discovered.

There is no discovery in Vettriano. There is labour but no substance. It is the work of a cowboy builder, working with shoddy materials, putting up a big house. I don't mind things being cheap. There is nothing at all wrong with cheap imagery. It is the pretending to be something else rubs me up the wrong way, that Vettriano's image is not even a case of 'all fur coat and no knickers', but that it is very much fake fur too: that is dishonest. Rather Beryl Cook. Much rather Beryl Cook.

1 comment:

The painting inspited a very good poem by David Kinloch. I'm sure it was up at his website, but the site seems to have disappeared and I don't have it to hand. Also, Edwin Morgan wrote a short poem on it in his A Book of Lives, which begins:

The skating minister is well balanced

And knows it. Something distinctly smug

Keeps those arms in place...

and then asks what might happen if God let him slip. That tipping-point between polarities...

Post a Comment