Sunday, 28 February 2010

Sunday night is... Mae West and Easy Rider and Anthony Julius

From She Done Him Wrong, Mae West and Cary Grant (looking a bit like Al Bowlly) in 1932 or so. A nice ten minute clip. She does a slightly watered-down Bessie Smith in the song, but I still like it. Her easy rider done left her.

Grant clearly reckons she's redeemable.

That's not a redeemable woman. At least she doesn't walk like one.

*

Read at the Jewish Book Week this morning with Bernad Kops and Micheline Wandor. Very nice. I wondered whether they'd want me to read exclusively Jewish material. I thought about it but then thought I wouldn't, not exclusively anyway. I mean it might make sense when invited to read poems to the Tottenham Hotspur Supporters Club to perform poems solely about Tottenham Hotspur, but generally I try to write about Burnley and Stoke and Bolton Wanderers too. So I read them a brief twenty minutes about the lower half of the league and hoped they'd recognise it as, at least, Premiership material.

Reading Anthony Julius on Eliot's anti-Semitism on the way down from York and generally ('never read anything less than ten years old' is a fine motto). It's perceptive, deeply read and very well argued, but I keep wanting to say, "On the other hand..." and "Yes, but..." And I wonder, for a while, why it is I keep wanting to qualify what Julius is saying. Then I think it may be that while I will read Julius's book once and profit from it, I will go back to The Waste Land time and again, for the rest of my life.

Which is not an argument, only a fact.

And that reminds me of my one and only Ezra Pound clerihew that goes:

Ezra Pound

Was seldom to be found,

For reasons too complicated to explain,

On the terraces at White Hart Lane.

Dad was a solid Spurs man.

Saturday, 27 February 2010

You look famous

Now installed in London hotel. Very full day with workshop in the morning, prize presentations in the afternoon, and reading straight after. All seems to go very well. In the lunch break I wander down a few old York streets full of tourists then drop into the Minster - which is quite magnificent. All three periods of Gothic densely and superbly represented and, having been used to Norwich Romanesque it all looks soaring and arrow-like and full of light, It's a central crossing and the choir is practising. Beautiful sounds - I can't identify the piece but it is a twentieth century work and the organ heaves in with its virtuosic thickness, sea-depth and star-height.

After the events we walk back part of the way together with Margaret, Rose and Peter, core organisers. The river is exceedingly high and it is expected to rise yet. The embankment is partly flooded already. The rain has stopped but the river is still on the swell.

The previous night we had gone for a meal and talked about local farming and the difficulty, they tell me, of finding good reliable British labour - the Latvians and Poles etc work hard, the British lads come late, slope off and don't return. I try to explore why that might be because I suspect the reasons are far from simple - class, history, the sense of respect the young male craves and how he might get it - and I think we come to some sort of common view on that. They themselves are good hard working honest people. I can see it breaks their hearts a little.

On the train home I am beset by Queen's Park Rangers supporters, just returned from Middlebrough where they got beat. Across the aisle a family, then a very big drunk man called Dave comes on and briefly snogs the wife. He is a threatening presence but the threat is latent rather than imminent - I don't mean for myself alone, I mean for anyone in his vicinity. He's a plumber. He claims to have drunk thirty cans of beer during the day. I doubt it as does everyone else. He starts talking to me, getting me in on his jokes. I feel surprisingly sanguine about all this. Then another supporter comes, nowhere near as drunk, in fact a calming presence. He inspects me and declares:

You look famous. Are you?

I tell him I'm not famous, but he insists I must be, and now the family and the big plumber are all interested.

What do you do? the sober one asks. I tell him. They look a little awed if sceptical. So I produce the big collected which does at least have a photo of me on the back as proof. I wish I could show them an airport novel or a book of crime fiction. Poetry? But it doesn't matter to them. It's a fat book. The wife, a nice put-upon-woman (especially by the fat slob drunken plumber, I think) wants to see it, so I pass it over. The big plumber doesn't know quite what to do with the famous looking bloke who is a poet, and he moves on amiably enough and doesn't return which is a relief to everyone including his fellow supporters. I decide I am in for a conversation and we talk about football and Queen's Park Rangers for half an hour or so.

The sober one tells me of the other famous person he once saw going into a match at Portsmouth. It was Claire Grogan, of 'Gregory's Girl'. He says it's his second favourite film of all time, and he wishes he had talked to her, seeing as she was there, because he thinks she is gorgeous and wonderful. But his wife wouldn't have it, he says.

We are getting to the liking each other stage, now that the fat dominant plumber has gone, but we live in different worlds. He is very happy to have met me, he says. I am flattered and touched. I am pleased to have met him too. The supporter, his wife, and their little son say a very friendly goodbye when they get off.

When I get to the hotel I look in the mirror to see whether I look famous or not, or why anyone should think I look famous. But all I see is the same old mug - a legend in his lunchtime as they say. Perhaps I should try to look more famous as this seems to be a generally good thing in society, but I don't really know how to go about it. I suspect it would be the end of me if I started looking distinguished to myself, so I leave it there. The QPR supporters are on their way home to the south coast. This trip will have cost them big money and big grief.

Friday, 26 February 2010

York in the Rain

Whithersoever he goeth he bringeth the rain with him. On the other hand, it's raining just about anywhere so I need not take the rap for this one. Some of the rain is pretty - particularly when seen through a window when all the drops landing on puddles make perfect circles, just as in those famous Japanese woodcuts. Some of the rain is wild - particularly at street intersections where I am glad to have a new double strength umbrella. Some of it is just plain boring and very wet - particularly at all those hours in between the pretty parts. A woman in North Yorkshire has died in a car swept away by the current.

Now I am in a hotel room - big but cold. The life of hotels: it's the same everywhere. I imagine a room shrinking then expanding, the same room every time. Spot the difference in amenities. I think there should be hotel rooms that provide the unusual. Canaries, for instance? The distant sound of tigers in the jungle? A big inflatable mosquito? Sunlight on rainy days?

On the TV it's the news. The woman who slept with the twelve year old boy two hundred times, apparently gave him a pair of trainers as a present on the hundredth occasion. Touching to think of her counting. Ninety-eight, ninety-nine - One Hundred! Perhaps she gave a great shout at One Hundred and Eighty, as in darts.

A three-hour workshop this afternoon on arrival. I think it was fun. I hope the class did. In half an hour I am being taken to dinner. This be the verse:

The rain it raineth on the just

And upon the unjust fella,

But more upon the just because

The unjust steals the just's umbrella.

I'll get my raincoat now.

Thursday, 25 February 2010

London in the rain

We have had so much rain it's more of a nuisance, and occasionally danger, swelling rivers, bringing down flash floods, than a thing of beauty that is a joy for any significant amount of time, but stepping out of the PBS in Tavistock Place this evening it was dazzling. The headlights are dazzling of course, but then so are the puddles that shimmer and are constantly on the move. Walking on the pavement is like a space walk: it doesn't feel quite like walking as we know it. So the new, strong umbrella goes up, but the water gets at you from underneath and you feel the bottom of your coat getting wet. But it is still more like Gene Kelly as in Singin' In..., than like Edward Thomas, as in this bleak hut and solitude..., Nothing solitary about this; it is a peopled rain, though a good proportion of those people are in cars, cars sleek as seals with the stuff and none of them moving fast, because it's the time of day paradoxically called rush hour, meaning the time when it is impossible to rush.

At King's Cross we are waiting for the platform announcement for the Cambridge train. The scene is much more like a rush hour should be. It is like the start of the London marathon, a kind of stumbling sprint for the insufficient seats. I sit opposite two Cambridge ladies of retirement age. One was an academic, or her husband was an academic, because she talks about the delights of still going to lectures there, particularly the science ones, she says. It turns out her husband or her husband's friend is an academic in Aberdeen. Behind them a young woman with an effortfully babyish voice is flirting with a bald man who is quite enjoying the distraction.

Cambridge is in the rain too. And come to think of it, Wymondham does not lack for rain either. Not so much Gene Kelly here as Edward Thomas...

Tomorrow to York for a workshop, adjudication and reading the next day, then the train down to London again for a reading at 11:00 am for Jewish Book Week with Bernard Kops and Micheline Wandor. My first ever invitation there. Someone must have told them I'm a nice boy. The programme looks very good indeed. Tempted to stay for Anthony Julius at 12:30, then at 14:00 its Will Self and Adam Thirlwell.

Wednesday, 24 February 2010

Where's the money, Lebowski?

>

>About 6pm tonight the telephone rings. It's an American from Barclaycard. He asks me my name and he tells me he's from Barclaycard. I ask him for evidence of that. By way of reply he asks me for the year of my birth. Strange evidence in which I have to give him information. But I give it, because that's not giving away much. And it turns out he really is Mr Barclaycard. He's hard, fast and aggressive. He tells me I owe Barclaycard a middling three figure sum that was due yesterday. I don't quite believe I owe him since it is a matter of principle to pay everything on the nail. I've been with this bank for forty-one years and never had any trouble, always paid on the dot.

Nevertheless, he repeats it a little more impatiently and more aggressively, as in, Come out with it, you cheap chiseler, what have you done with it? I am beginning to resent this. I ask C what she knows about it. She hastily looks up the statement in her desk and says we've paid. I tell him we've paid. On line. He doesn't believe me.

C checks again online - all this takes about ten minutes because online is slow. Eventually we spot a mistake. She paid the sum owing on my card through her card. Five days ago. There is only a single number difference in our cards, and she is dealing with her father's estate and her sick mother, and I am dealing with my father's death and estate. The money has actually gone out of her account. Barclaycard have swallowed it, no questions asked.

Never mind that, we now owe Barclaycard a penalty of just short of £30.00. She has to use the credit on her card to pay for something she bought, and I have to pay out the figure plus the £30 and put up with the man's absurd rudeness. This is about 24 hours delay. He could have begun politely, like 'Do excuse me Mr S, sorry to bother you but...' but no. He's the bailiff with the shotgun.

Result: I write a letter straight to Barclaycard to say we are both leaving. No more credit cards from you. Thank you, Barclaycard, and no thank you. Thank you modern banking. Custom goes elsewhere.

Now I look down the pan again I think I see the money by the U-bend. In fact I'm sure its down there somewhere. Just push my head down once more and give me another look, would you?

Tuesday, 23 February 2010

Terza Rima - a defence of rhyme

Dante’s terza rima is one of the supreme metrical inventions in the history of poetry. But in spite of several, if not very numerous, attempts, the metre has never been acclimatised in English.

- Laurence Binyon ‘Terza Rima in English Poetry’ English, 1940

[I am commissioned to write a longish article on terza rima for a new reference book called A Companion to Poetic Genre - the deadline approaches so that has been the work for today. Not finished yet, of course - only about half way through.

The piece begins with definitions, as it has to, and it moves on to Dante and the various translations available, some in terza rima, some in plain tercets, some colloquial, some prose - but the piece is not on Dante but on terza rima. So this is how the argument goes for now. ]

*

The one thing everybody knows about terza rima is that it was first used by Dante for the Commedia, invented by him for the purpose. The second is that there is a paucity of rhyme in English which is the reason it has not been much used by English language writers...

...The cornerstone of the argument [against rhyme] is that English is not a properly inflected language so the regularity of verb and noun endings deprives the poet of a wealth of possibilities. But inflection rhymes are thought to be rather cheap in many languages. In Hungarian, for instance, they are called ragrím, and mostly disdained by serious poets. It is as if a serious English language poet were proposing to make substantial use of rhymes ending –ation, or –ness, the first resort of the vocabulary-poor who need a bit of bling to make it swing.

A greater problem is the large range of English vowel sounds. Our five written vowels resolve, according to The International Phonetic Alphabet, into thirteen distinct vowel sounds, to which should be added up to twelve dipthongs. That is without the regional variations. (It’s not surprising that foreign speakers of English are more easily given away by their vowels than by their consonants.)

But the problem is not insurmountable, because various departures from true and full rhyme are permitted, eye-rhyme among them, where it is the spelling rather than the sound that does the rhyming work. A number of these were full rhymes once. But we may allow ourselves greater or lesser consonantal variations, accentual variations, and licences of many kinds. We might even think full rhymes a little childish, or a little too insistent.

Milton, in his famous preface to Paradise Lost, said:

The Measure is English Heroic Verse without Rime, as that of Homer in Greek, and of Virgil in Latin; Rime being no necessary Adjunct or true Ornament of Poem or good Verse, in longer Works especially, but the Invention of a barbarous Age, to set off wretched matter and lame Meeter.

No doubt he is right in that rhyme is absolutely not a necessity in poetry, not even as adjunct or ornament, however, a defence of it might be made along lines less traditional, not as adjunct or ornament, but as structure. In this defence the issue of ornamentation is unimportant.

This is not the place [meaning such a piece] to develop such an argument, but since terza rima inevitably involves rhyme in its rima, a very brief attempt might be made. The defence would argue not by way of the final product but by way of process and the relationship between the user of language and language itself.

The proposer might argue that the act of finding rhyme is a different sort of negotiation from employing metre or, in fact, writing free verse. Finding rhyme is the constant deflecting of some possible intention. The poet may wish to say something then seek the words in which to say it, but rhyme constrains the process. Intention is necessarily modified. Out of that modification arise various new active possibilities. Language itself is more active as a result: its accidents, its demands, cannot be ignored or overridden. Thought must move differently and take a less directive role.

Since language in poetry is of primary importance – it is interesting how translations of Dante that depart from terza rima shift the reader ever further from verse as verse and closer to story as story, a story in which form plays a less active part – it might be argued that the active, volatile, aspects of language as sound beyond instrumental meaning are of particular interest.

Whether poetry is capable of being paraphrased (rather than summarised) or not is a moot question, but it could be argued that the effect of shifting Dante from terza rima into blank verse is to rewrite the poem as paraphrase with ornamental features, that is to say with local effects that heighten descriptions and moods. The story then is the real thing: its poetic qualities are the adjunct (the Sinclair translation is, in fact, prose).

The argument against rhyme also turns on the dangers of doggerel and cliché. Rhyming moon with June is certainly a cliché given the appropriate cliché context, but the art of rhyming – and English poetry is full of wonderful poems that do employ rhyme – lies in avoiding cliché, which is, essentially, easy closure.

The last major strand of the argument is based on the old antithesis between the modern as in Modernism and the traditional as in everything else. After over a hundred years of Modernism it may be the case that a device like rhyme need not insist on some pre-lapsarian, conservative caricature of tradition, but that it may take full cognizance of all that has happened and begin to define its function according to different principles.

That is as far as the defence of rhyme need go for our purposes here, but it I hope it might have been useful to sketch out a territory if only because, while it makes perfect sense to speak of an unrhymed sonnet, it makes no sense at all to speak of unrhymed terza rima.

*

[Then I look at Chaucer and Wyatt and will go on to Milton and Shelley etc, through to Walcott's Omeros, which employs terza rima in a generally loose but highly effective fashion.]

Monday, 22 February 2010

Submerged optimism

The current issue of bullying in Gordon Brown's office, whatever the resolution - and I doubt there will be one - is another step in the (self) discrediting of politics in this country. Smear and counter-smear alternate, the spin spins ever faster, and the centrifugal force is likely to throw a good many people off whatever mechanism we picture doing the spinning.

National Bullying Helpline's Christine Pratt rushes to deny the denials of the Prime Minister's office, as a result of which Anne Snelgrove, of the Prime Minister's office, sends a batch of emails making serious allegations about Christine Pratt to the Today programme. Pratt denies having claimed that Brown has physically bullied people and denies having refused a meeting with Snelgrove to discuss the allegations about her. She denies insisting on having lawyers present. Snelgrove says she resigned as patron of the charity not because of the allegations but because she didn't want a meeting with lawyers present. Pratt denies having asked for lawyers to be present but asserts that it was necessary to have trustees (not lawyers) because that's what the constitution of the charity says. Snelgrove denies having turned down further invitations to meet, denies that Brown is a bully, though Pratt denies having said he was. Perceived smear, counter-smear. And the facts?

Either one or the other is lying, or - more likely - both are being a little liberal in their interpretations of what actually happened. That is what, I think, may safely be called spin. The fact that Snelgrove is spinning in mud, and that Pratt might or might not have her own mud to spin in, is irrelevant. The point is the mud. The point is the spinning. Whether Gordon Brown ever grabbed anyone by the collar or not does not seem to me an issue of national significance.

On the other hand the sound of Gordon Brown's office wanting to appeal to the 'submerged optimism' in people sounds less like mud than a desperate wallow in unadulterated shit. It's not a question of whether the economic policy is right or wrong, whether it is better to make severe cuts so as to reduce the massive debt or to allow the economy to somehow reflate itself. I don't know. I know my 'submerged optimism' would prefer the latter simply because, by definition, optimism would choose the more pleasant course. I don't want to know about my 'submerged optimism'. It is the submerged optimism of the government that is at issue. Do they actually believe in their cure or is it just for public consumption? The fact that a general election is rushing towards them at great speed suggests to me that 'submerged optimism' is, like patriotism, the last refuge of a scoundrel. 'Look,' they cry, 'just think of nice things and vote us in again!'

We've already been through months of MPs' perks. I want politics to work. I want debate and I want a modicum of straight dealing - not saintliness or even a collection of figures entirely beyond reproach - but a necessary modicum, let's say 80% or so - without which politics is just a private casino. For the first time in a long time I have serious doubts where to cast my vote. God knows, I might go Green, but for the fact that an essentially one-issue party seems unsatisfactory to me. There is a slow collapse in process and something has to be built out of the ruins.

*

In Hungary on the other hand everything is crystal clear. The rise of the extreme right party, Jobbik, that polled 15% in the European Parliament elections and is polling at 10% now, that is to say well over the 5% barrier required to get seats in parliament, is, apparently, all the fault of the liberal-left, according to the 'centre right' think tank, Budapest Analyses (I get emails so can't link directly). The liberals and the left are corrupt and they keep blaming right wing extremism on, er, the right. In this way they drive people to the, er, right.

As they say:

while many delve into the role of the right-wing media and intellectuals in the growth of Jobbik, the responsibilities of leftist-liberal politics and intellectuals for this development is little discussed.

And:

The result of left-wing governance in Hungary has been a marked degradation in the social and economic situation. Part of this trend is the attitude popular among youth that identifying with far right ideas is a way of rebelling against the political establishment. In reality, this means that the self-sytled leftist and liberal intellectual community – probably as a result of its unquestioning support for the extremely unpopular Gyurcsány-Bajnai line – lost its credibility and can no longer be attractive among youth. One contributing factor in terms of the territorial aspects of Jobbik’s surge was mounting tensions among the Hungarian and Roma population due to growing poverty across the society.

Furthermore:

while weakening the Hungarian state administration they degraded the police’s efficiency, which in turn strengthened the perception of flagging public security.

Clearly what is wanted is a stronger police, with greater powers.

And, the trump card:

In Central Europe, and so in Hungary, the strategy of continuing to raise the specter of Fascism as the alternative of the left is a legacy of Communism. In practice, this means trying to blur the distinction between the centre-right and the far right.

In other words the act of describing fascist parties as, er, fascist, leads more people to become fascists.

Bad mistake, thinks Budapest Analyses. Not half enough submerged optimism there. Look, they're not really fascists and they are not really murdering Roma - and we have no sympathy with them, that's just a smear, and anyone who thinks different is a Communist.

Sunday, 21 February 2010

Sunday night is... Jake Thackray

Jake Thackray's face always reminded me of Buster Keaton, but his model was Georges Brassens. And the song below, which shows him performing, brings that home as it is a version of Brassens' own.

'Sister Josephine' was his greatest hit, but all the songs are witty, sad, stoical and a little bruising. Or just downright hilarious. We were talking about him last week before a reading. He was a Leeds boy. A words man but with some subtle tunes and his own idiosyncratic phrasing.

Saturday, 20 February 2010

Angularity: Eve Arnold x 2, Caravaggio x 1

Elizabeth Hester Douglas-Home, Baroness Home of the Hirsel; Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel, 1964

Marilyn Monroe

As an art student I learned about the dynamism of the diagonal. I look at Lord Home's knee and Monroe's elbow and sense that things are being a little flamboyant. Something angular, akimbo, jagged, yet stylish about the position. It is a sharp thrust in a particular direction. The Lord Home sense of being master in one's own home, the Monroe gesture, however functional, of being able to extend and own space - and to counter the cop's own jagged elbow. Fascinatingly both Monroe and the cop's elbow are contained within the verticals of the furniture behind them. There would be much greater aggression if either elbow broke the vertical. Neither does: thereby a certain propriety is observed.

Eve Arnold was probably Monroe's best known photographer, but she was much more. Certainly she was interested in glamour and pose, but she sees the brevity of such things, and brevity is what such angularity signifies. The proprietor strikes a pose he cannot keep for long, the film star's arm would soon begin to hurt. But both settings are brought to life by the strangeness of the position, the way it intrudes into space. I think a little of this:

In Caravaggio's Supper at Emmaus, the elbow of the apostle, unlike that of Monroe and the cop, does break a barrier: it breaks the picture plane and thrusts itself into our faces. The elbow is poor and patched. It is, briefly, a revolutionary pose, a revolutionary moment. The angle is aggressive as anyone's poke with an elbow would be. Our normal idea of grace is fluid, not jagged: the sinuous curve, Hogarth's serpentine line of beauty, the arabesque.

But we think of lightning as jagged, and lightning is not considered ungraceful, it is only that it is felt as sublime.

The Lord and Lady Home picture is rather gorgeous for its black serpentines too of course - the dog, Lady Home, the sportif cockerel ornaments on the wall.

The sun has been out all day but the air is still chill. I have spent the hours reading submissions - some of the many submissions - for a writing fellowship at the university. It's close to ten o'clock.

Friday, 19 February 2010

Papers and papers and papers: a document trail

The beginnings

Spent two thirds of daylight hours putting my father's documents into order, beginning with my mother's Romanian birth certificate (born 17 February 1924), as supplied in 1965. But then my father's school report from school year 1932/33. Religious and moral education: Distinction. Only Satisfactory on Law and Chemistry & Technology. The matriculation certificate 1934/5: Merit. The 1937 paper that classifies him as Jewish. Another one saying the same thing, only more so, in 1939 for his father. Another certificate permitting him to be a plumber's mate in 1940. His work permit papers of the same year. Then, after the labour camps in the Ukraine and Belarus, the change of name certificate of 7 July, 1945.

Post-War

An ID of the same year in both Hungarian and Russian. The party card of the Social Democratic Party (a far more left wing organisation than we understand here, and soon to be absorbed in the Hungarian Workers' Party, ie the Moscow Communists). The wedding certificate of my mother and father, giving my mother's name as Magdolna. My own birth certificate. My father's pass of 1949 stating his occupation as 'general mechanic' (a photo with it, a fag drooping from his mouth). By 1950 he is in the Ministry of Works as Department Leader. This involves a new photo, the address the one where I remember living. In 1954 a letter from the deputy minister complimenting him on being an outstanding worker and announcing a pay rise. A little certificate (no. 1186) in card form to declare him an outstanding worker of the building industry. In 1955 another letter, typed on yellowed paper, giving him another pay rise. Two hard-covered IDs, one from 1951, one from 1954. My mother's ditto, her photograph very Katerina Brac. My younger brother's diphteria certificate.

Revolution and Emigration

Then the revolution. And, after the failure of the revolution, a small signed ID permitting him to travel to Györ near the border on official work. That is when he takes us with him, and we move on to a border village, from which we walk the rest of the way into Austria.

Leap forward - two British Home Office forms permitting my mother and father to "land in the United Kingdom on condition that he registers at once with the Police". On the reverse side, hand written, a list of basic household and hygiene items in English. Also 10 December a Registration Form from the Hungarian Refugee Department of the British Council, based at the Carlton Hotel in Haymarket, giving basic personal details.

The Australia Question

Next the Australia saga of 1957-58 - a series of letters from Australia House responding to my parents' requests to emigrate to Australia where my father's cousin has been living since 1948. The first (13 March, 1957) asks for a medical examination. The next is very strange indeed. It is not from Australia House but from the Jews' Temporary Shelter on Aldgate, who must have been in charge of the arrangements. Two letters of the same date (13 May), from the same place, signed by the same person. One says a reservation has been made for the family to sail on the SS Sidney on 25 May. All we need is a visa. The other says the visa cannot be issued so we cannot sail on the SS Sidney after all. 'However', the letter ends, 'you can be assured that as soon as visa is issued to you transportation to Australia will be arranged'. Then on 10 July Australia House insist on a second medical inspection. On 30 July from Australia House a rejection of the application. Our address at this time is the maisonette in Hendon in a now-demolished house. (A wasp flies into my ear one night and stings me. Terrible pain.) One more letter, this time by air, directly from Australia (25 Sept) turning us down again, but not saying why. The correspondence is continued on 18 November, with a final appeal on 3 April 1958.

This sounds dry stuff - but it's a life, in fact four lives.

Maybe a little more of this next time.

Yellowed papers, carbon copies, names misspelt, letters offering employment, letters offering furniture and household items. Naturalisation papers. Papers cheered and wept over. Papers stuck in files, in envelopes, between other sheets of paper, some falling to pieces.

Very late - a good citizen

Home from Cambridge, via London where we had gone to continue going through my father's belongings. Mostly paperwork still but it's the other things that begin to get to me. His study / office was the small extension room of the bunglow - the size of a box room. Cold in there and the ceiling light not working. The room packed with two chests of drawers, a cupboard a desk and two chairs. Orderly the whole of his life, he had let it go a little this last year. There is a drawer full of chocolate boxes with chocolate in.

Two drawers with useful odds and ends - electric plugs and such things. The papers in essentially three drawers but more papers elsewhere. The desk with hospital correspondence, Hungarian scout magazines. One desk drawer full of charity envelopes, mostly unopened now. More charities there than I knew existed. A paper knife. Two old typewriters. A box full of the home made cards we sent him year after year. A good selection of my own books on the wall-mounted shelves. A few reference books. Travel brochures in another drawer. More scout magazines in a neat chronological pile.

And some very old folders - his documents and my other's documents. His military pass book, his Social Democrat party membership book. His Hungarian ID. And early letters in England. One moves me to tears briefly. It is from the refugee council congratulating him on his first house - a house they helped him buy - and telling him how glad they were to have him, how glad they were he was happy and what a good impression they have of him as a future citizen. Words to that effect. I remember the house very well. It is the one in which he is sitting in that earlier photograph a couple of posts down - along with the spiky pot plants and the bent-metal figurine - dapper and earnest, elegant, a touch self-conscious - a new man in a new life. 1958. Much else to go through. My mother's death certificate and her papers...

Then we drive to Cambridge where I read to Trinity College Literary Society - some twenty people. It goes very well. Afterwards a quick drink with two PhD students, George Younge who invited me and the Australian poet Jaya Savige. The Lion Yard car park is a nightmare. Everyone wanting to get out and no one moving - a vast half an hour snarl up and the worst piece of car park design I have ever come across.

Rain all the way until we get to our own small town centre where it finally stops.

Wednesday, 17 February 2010

Two anecdotes and a phone calll

1.

Visit to solicitors this morning to start the process of probate for dad. Solicitor tells me the story of the family of spiritualists who were his clients, after the son took his own life. He said the parents conducted a conversation with the dead son in his presence, taking advice on various matters. A year or so later the father died and the solicitor went over again. The mother now conducted a conversation with both the dead husband and the dead son as well as with him. It turned out the the father had premium bonds and that he had four winning numbers.

2.

At lunchtime I talk to prospective undergraduates again then have to dash off because the RNIB have booked a conversation with me as part of the book group's 'meet the author' sessions. I take the phone call on my university office phone. The other six or so people are sitting in their own homes with their own phones, with a facilitator somewhere else again, to help the conversation move. They have had two of my poems and I am asked to read them again. The group is mostly older, some twenty years older than I am. One lady reminiscences about remembering Bellow's Cautionary Verse, Jim. One of the men is quieter until he is addressed directly. He says his favourite poet is Shelley. I mention The Masque of Anarchy. He begins to recite it in a powerful voice and continues. It is marvellous to hear him and no-one interrupts. 'I was a red in those days,' he says when he is finished. 'I liked my poems the way I liked my steaks - with plenty of blood.' We talk for an hour.

3.

I am home in the early evening when the phone rings. It is my father's younger sister from Buenos Aires. She wants to know what's happening. I'd rung them originally to tell them of dad's death. I tell her all about the funeral, about the family, about the will, about the work to be done. Do I mind her ringing me? She is ninety. I say of course not. Because there was a long feud between my mother and my father's side of the family - a terrible feud that went on for years, throughout my conscious life at home. Details are referred to in the long poem 'Metro'. Am I still angry? she asks. No, I have never been angry. I was just a witness of anger. She says it is very cheap for her to ring me. Two hours for three dollars. Can she ring again? Of course, I say, at any time.

Tuesday, 16 February 2010

Some excerpts from the funeral of László Szirtes

The funeral took place on the 11th. Here are the four excerpts from his reminiscences - very much edited to take up about a minute and a half each. We were all working to a very tight timetable. The voice is not his, not really - the life is.

1. ANDREW (My younger brother)

I was born in Budapest in a small clinic in Ferencváros in 1917. Two and a half years later came my sister, Lili, and two and a half years after that, my little brother, Endre, who was to be killed in the sandpit accident in 1930.

At the time I was born my father was working in a leather and shoe factory in Újpest, on the outskirts of Budapest. He had to be in the factory by 7am, so he got up at 5 and left at 6. He was a cutter - that is to say he cut up the leather. This was skilled manual work. My mother did sewing at home to earn more money. She got jobs through friends, by word of mouth. She never advertised.

My grandparents on my father’s side, were old, gentle people. He was Gábor; she was Mária. He was a tailor and had a small shop very near to their flat. He worked there until he was 73 years old and could hardly see. He loved the family and his grandchildren - especially me for some reason, mainly because we were nearest to them.

His two daughters, Riza and Tini lived with them. Riza lost her only real love in the First World War. She never got over it, and sacrificed her life to looking after her parents. Tini was plain and resigned to doing the housework with my grandmother. I was really brought up by them.

2. TOM (our son)

The flat was in Eötvös utca and consisted of two rooms, a kitchen, a little hall, and an outside toilet. No bathroom. The rooms were pretty dark, on the first floor of a four storey house, looking down to the yard. My parents had a very small flat, which is why they were quite happy for me to stay with my grandparents.

I didn’t mind. I loved the arrangement. I usually slept in the same room as my aunts. The other room was the dining room and in it were the two single divans where my grandparents slept. All the walls were painted a light colour, a yellowish tone. There was very dark old brown furniture.

I was very pampered, the little bright chap of the family and they spoiled me. Every day my aunties would go down to the confectioner’s or the baker’s to get me a little bit of pastry or mignon to put on the table for when I got home from school about one o’clock.

I had friends in the same block with whom I played football in the corridors or with buttons on the table. Or we would go out to a small park nearby which was all earth, without any grass whatsoever. There were a couple of swings there. There were few such places in Budapest, usually poorly kept.

My parents had little social life. Sometimes on Sunday they’d go to the local cinema to see the silents, and, if they took me, I would sit on my father’s lap to watch. In summer we might go to an open air café in Varosliget where there was an orchestra playing.

3. HELEN (our daughter)

I finished high school when I was sixteen years old and the first thing was to find a job. Anti-Jewish laws meant I couldn’t go to university. At this stage I was qualified to work as a clerk in an office, and through my uncle I was introduced to a company that manufactured, sold and exported textiles. The factory was outside Budapest but the office was in town, near the basilica.

My name being Schwartz (meaning ‘black’) everybody called me Fekete úr (Mr Black in Hungarian). They didn’t want to call me the Jewish-sounding Schwartz in front of so may people. They asked me if I minded and I said no. Fekete, Schwartz - both were fine by me. Every day I had to walk the twenty-minutes to the office and whenever I passed the basilica I muttered to myself: EGO SUM VIA, VERITAS ET VITA – the text written at the top of the church.

After about two years, one chap in their export department, left the company and, as I had taken English at school – and because the company exported a lot of goods to British colonies, they asked me if I would like to move there. I had to write letters in English, which I enjoyed. I had a very good book of commercial English correspondence and learned a lot by reading it in the evenings.

At that time, every Sunday, I went hiking with the scouts, but in the summer of 1936 the original boy scout troop of which I was a part, the Toldi, was dissolved because of racial laws. It was Hitler’s rise to power that precipitated all this. The year I finished high school was the year Hitler came to power.

4. REUBEN (Andrew's younger son)

In November 1943 we got the order to clear out of Berdichev in The Ukraine, and the Germans, who by that time, had taken charge of us, told us to put all the Hungarian supply-unit ammunition onto one train, and twenty-five of us, including me, were ordered to go with the wagons. The rest were ordered to march back – many of them dying along the way.

We were told no destination except to go west. We had with us three Hungarian soldiers who spoke no German. After several hours of travelling we arrived at some large town where the place was buzzing with Germans. The Hungarian soldiers leapt off and tried to report to the Germans but were unable to make themselves understood, so one of our friends Gabi Karcag, who was fluent in German, jumped off and went to interpret. The German officer asked him where we were going. Karcag replied that we didn’t know because we hadn’t been told. The German asked him where we had come from and Karcag – interpreting the question as where had we originally come from, replied - quite truthfully, -that we came from Budapest.

‘In that case,’ replied the German, ‘that’s where you’ll go.’ And he had a piece of paper pasted on to the side of the wagon saying ‘Mach Budapest’. The officer - I think his name was Krank –wired through to various stations on the line that this was the train which had saved the ammunition of the Hungarian First Army from destruction by the Russians. And believe me, at every station we were greeted as heroes.

As soon as we arrived in Budapest we were placed under house arrest and sent back to Russia.

It is nothing much when it appears like this. Much more to come, now and then - later.

But I have had some lovely letters and cards remembering him:

'...I did meet him once, a long time ago, at your home and warmed to him immediately. It was just a brief meeting - but some people, actually only a few, are instantly memorable, and your father was one of them....'

'...But of course, with all its vicissitudes, an extraordinary life and a splendidly long one - we can hardly say we knew him, but our glimpses of his cavalryesque chic and charm were irresistible...'

'...I have such a vivid recollection from the one occasion when we met at the gallery. He represented that lost world of Budapest that I loved - civilised, cultured, worldly... what your father conveyed was warmth... so reminiscent of the old world of 'Mittel Europa' with his charm and genuine friendliness'

He must have made quite an impression. I had never once imagined my father in the cavalry; chic was not a term I would ever have used; nor could I ever quite know the impact of that charm. I had him all the time in my childhood after all - that's in so far as one ever has a father 'all the time'.

He was not an exotic flavour to me. If he was paprika, I was used to paprika and still am. But I love hearing others' impressions.

Monday, 15 February 2010

Late again - points mean prizes

Back from Cafewriters in Norwich at Jurnet's Bar, where I was handing out cheques to the winning poets in a national - nay international - competition, and some applause to the shortlisted ones. The best were very good indeed. Here are three of the young ones to keep an eye on: Helen Mort, Thomas Warner and Richard Lambert - all outstandingly talented. I have a feeling that the next generation is going to be quite something.

Here is part of the judge's report which may be of some use to people entering poems for competitions.

A very high number of entries - c. 1600 – meant it was bigger than most regionally offered prizes. It is, in many ways, encouraging to have so many poems since it indicates that poetry is a natural recourse for far more people than we would think.

However, if you want to write good poems it is essential to read some of the best poets, both historical and contemporary, and to form some notion – conscious or unconscious – of what makes the good ones good.

It is also good to be aware that poems are not statements about life, they are explorations, and the best poems don’t simply tell us what the poet thinks in verse but explore what might be thought and felt while listening as keenly as possible to language. No listening: no poem. The apparent simplicity of the best poems is in fact a distillation of different, sometimes even contrary feelings. And that, after all is true to life because, as people, we can feel several ways at once in trying to understand the world.

I say ‘verse’ but must add that the great majority of the poems were in free verse. Free verse is not free for those who write it well. It is as difficult as formal verse if you do it properly. You think you are let off the leash, that there are all those unimportant elements you need not worry about, but poetry itself is a leash, as is language as a whole. Poetry doesn’t run everywhere: it still has line and length and development, and you have to attend to those all the time. Cadence, rhythm, phrasing and development are all part of it, as they are of music, from which these terms are taken. Nowadays people tend to go in mortal fear of writing doggerel. Doggerel does at least impose shape. Where and how do you break a line? Why there? Push harder. Think harder, feel harder. In any case some of the more competent formal poems held their shape better than most of the relatively competent free verse poems.

Or so it seemed to me. The rest of the report - and it was quite long, discussing everything commended - was about specific poems. Quite splendid poems too, the best of them. And very well read on the night.

Tomorrow, I am at home, doing the necessary things.

Sunday, 14 February 2010

Sunday Night is... The Four Seasons

Last night I finally finished the redraft of the Márai. Off it goes to Knopf with my blessings - just as soon as I've finished this post. The very last part of the book had been redrafted two or three times already so I felt I could pre-celebrate with some music while checking through. I just picked something out of one of the CD drawers and it happened to be The Four Seasons. I was typing and wanting to dance at the same time, so I did stop and dance a little, then sat down again. Then got up again and sat back down again. The harmonies are like the Beach Boys but it's the sheer bursting simplicity of the music that's such fun. I felt I needed some fun. Then I finished the redraft of the redraft of the redraft and sent it to myself by email lest some dreadful accident befall the computer before it gets to the USA across the troubled waters of the Atlantic. I slept well and deeply and didn't wake as early as usual.

Sunday morning is the time my father used to ring for a chat. I woke remembering that, as did C beside me. The sun was brilliant. I sat down to write a poem, one of the series based on postcards front and back that I am writing as part of the art-writing collaborative project with Caroline Wright, Helen Rousseau and Phyllida Barlow. I have three poems so far, of two parts each. I have found both the earlier ones exciting to write, then everything stopped. Now it started up again. The new one too excites me. Having produced a draft I had the urge to go to the sea and asked C if she wanted to go. But it was lunchtime and clouding.

A sudden wave of depression washed over us both. I sat down to watch the football on TV and slowly cheered. The match ended. The sun was out again, so we went for a walk. The light was unearthly beautiful - to call it golden is to insult it. It was clear and long and dazzling, everything extraordinarily luminous. Goldfinches again, maybe a greenfinch. And a tiny flittering, zipping bird across the river we couldn't follow. Perhaps a kingfisher? There are kingfishers there. And back by the abbey, the towers pure Samuel Palmer, visionary period.

I have not done a single practical thing today in respect of my father's accounts and savings. One day off. Tomorrow it's university then, in the evening, I give away some prizes and read a few poems. More work in store - plenty of it to come, of all sorts. I read in Cambridge on Thursday night - at Trinity College.

And I see Wayne Bridge did not break his leg but played very well. Not that his team won - no, they play again against friend Stephen's heroes. I rather fancy the Stokies to win.

The YouTube here isn't particularly good - lipsynch- but it's OK. It will do.

Saturday, 13 February 2010

Love rats

I hear Fi Glover this morning talking about the John Terry affair. She begins by saying something about the hurt and pain for the women (plural) involved.

There are four people as far as I know. Let's call them John, Toni, Vanessa and Wayne. According to the Glover doctrine the scene in the confession booth would go as follows.:

John: Forgive me, father, for I have sinned. Despite being married to Toni, I caused her hurt and pain by having an affair with Vanessa, who has also suffered hurt and pain because I had an affair with her and now she is in the public eye and this is liable to do immense damage to her career as a lingerie model. I feel no hurt and pain because I am the cause of hurt and pain for them both.

Toni: Forgive them, if you must, father, for they have sinned. I feel the hurt and pain that is caused by John on account of his affair with Vanessa, who, poor thing, is also feeling hurt and pain because she had an affair with John. If only Wayne had not given Vanessa hurt and pain to start with she would not have become the innocent instrument of the hurt and pain caused by John. Wayne, therefore, deserved all that was coming to him

Vanessa: Forgive neither of them, father, for they have sinned most grievously. I feel hurt and pain because I am in the public eye because of my affair with John, but also because Wayne thinks he owns me thereby causing me more hurt and pain by preventing me having affairs with people like John who made me have an affair with him, thereby causing me yet more hurt and pain. I myself have caused no hurt and pain.

Wayne: Forgive me, father, for I am the worst of sinners. I caused Toni hurt and pain because my girlfriend, Vanessa, who is, naturally enough, associated with me, had an affair with John. I must have caused hurt and pain to Vanessa too otherwise she wouldn't have had an affair with John. I myself feel no hurt and pain because it's what I deserve, and who, after all feels any sympathy for a cuckold?

Yes. That's how it would be. It's the women that get all the hurt and pain. Let's hope that swine, Wayne Bridge, breaks his leg in the next match.

Friday, 12 February 2010

So now it's over...

The funeral was yesterday. The crematorium is like a doctor's surgery: one in, one out; next in, next out. It's a brisk business. Timing is important. The clock faces you as you enter the small chapel. There are about five rows of pews, a lectern with a microphone and a button to push to draw the curtains. The coffin lies on a table on a dais projecting into the hall. It is up to the convenor (is that what it is?) - in this case, me - when to push the button. Frankly, the coffin means nothing much, though the drawing of the curtains can't help but have a heavy symbolic effect. Everything about the chapel is new, polished, non-committed and efficient. It's like entering a lift in a three-star hotel or a conference centre, travelling a few floors, then getting out again. Perfectly horrible in other words.

I have a memory of my mother's cremation in 1975 that still chills me. There was nothing in the least personal about it. There was a religious figure who mouthed generalities and a few quick facts mugged up from my father, and the coffin disappeared behind steel doors as into an oven. Not a good pun for my mother. And there was Martin Bell's funeral where a clergyman kept referring to him as John, presumably the first name on his birth certificate.

So we made our own as many do today. We arranged the furniture in the lift: we pushed our own buttons. The music - my brother's choice - was being administered by a man called Gary, in another room. You hand him the CD's. Brother Andrew was to play the violin with a CD orchestral background so he needed the volume turned to full so he could hear it while playing. To Gary this is routine and this was slightly out of routine, possibly mildly annoying. So unprofessional.

But the service was good, moving but disciplined, and better attended than we had anticipated. I thought there would be, at most twenty-five people including us, secretly anticipating about fifteen; but it was thirty, the elderly and frail rousing themselves, making a considerable effort to get here. Andrew and three of the next generation did a fine job of reading the brief extracts from dad's recorded memoirs. Andrew played the Meditation from Massenet's Thaïs, beautifully. It was after that I pushed the button to draw the curtains. Then I read my address - just five and a half minutes - and, finally, Clarissa read the poem below, the last of 'My Fathers' series. Her voice broke near the end and I took over. Exeunt to Beethoven's No 6, the Pastoral.

Brisk file past the flowers ten back to the house where he lived with K, to sandwiches and bits of cake served by Erzsi, the Transylvanian woman who had been some cleaning for them. The youngest generation, elegant and handsome in their suits and dresses; the elderly, smiling and milling and leaving. Six of my own generation. And then away.

But the service was a proper shape. It was about him. It said some of the things that mattered. Now come many more practical affairs with the pulses of memory kicking in, fading, then kicking in again, as must happen.

Like a black bird

Like a black bird against snow, he flapped

Over the path, his overcoat billowing

In the cold wind, as if he had trapped

The whole sky in it. We watched trees swing

Behind him, lurching drunkenly, blurred

Bare twigs and branches, scrawny bits of string,

And as we gazed ahead the snowflakes purred

In our ears, whispering the afternoon

Which grew steadily darker and more furred.

His face was in shadow, but we’d see it soon,

As he approached it slowly gathered shape:

His nose, in profile, was a broken moon,

His hat a soft black hill bound round with tape,

His raised lapels held his enormous eyes

Between them. The winter seemed to drape

Itself about him as if to apologise

For its own fierceness, hoping to grow warm

Through physical contact, and we, likewise,

Ran towards him, against a grainy storm

Of light and damp. It was so long ago

And life was then in quite another form,

When there were blacker days and thicker snow.

*

From here on I will post the occasional excerpt from his own reminiscences. Not straight away. Tonight I read in a Norwich bookshop along with some of the youngest and best for St Valentine's Day. Back in the weave of life.

Thursday, 11 February 2010

Two more poems from the 'My Fathers' set in Reel

My father, crawling across the floor

He crawls across the floor. His dangling tie

Distracts the child. He hauls the child in the air

And swings it round, once, twice. He holds it high

Above his head. In the forest, a bear

Lurches towards the cabin. Almost night.

Goldilocks sits in the deepest chair

By the table working up an appetite.

Time starts up, judders and stops again

Its flooded engine refusing to ignite.

We’re conked out here, stuck in the slow lane

Of history, where my father comes home late

From work as always and will not complain.

Seventy-two hours he labours for the state

Weekdays, Saturdays, doing what, why, how,

We do not ask him, but accept his fate.

Time is forever in an endless Now

Except in dreams, anxieties, and school,

Though time ticks over far behind his brow

According to a superimposed rule

We touch when we touch him. We hear him roar

In distant forests where his masters drool

And lumber playfully across the floor.

My father carries me across a field

My father carries me across a field.

It’s night and there are trenches filled with snow.

Thick mud. We’re careful to remain concealed

From something frightening I don’t yet know.

And then I walk and there is space between

The four of us. We go where we have to go.

Did I dream it all, this ghostly scene,

The hundred-acre wood where the owl blinked

And the ass spoke? Where I am cosy and clean

In bed, but we are floating, our arms linked

Over the landscape? My father moves ahead

Of me, like some strange, almost extinct

Species, and I follow him in dread

Across the field towards my own extinction.

Spirits everywhere are drifting over blasted

Terrain. The winter cold makes no distinction

Between them and us. My father looks round

And smiles then turns away. We have no function

In this place but keep moving, without sound,

Lost figures who leave only a blank page

Behind them, and the dark and frozen ground

They pass across as they might cross a stage.

*

Before setting off for London. Just one poem for the funeral itself - the one from the same set that I'll put up tomorrow. C will read it, not me.

Wednesday, 10 February 2010

An early UK shot and two poems

Part of the day completing and printing the order of service; arranging / negotiating who is doing what; writing the brief five minute address. The rest of the time, working our way through the jungle of his savings and pensions. It's not that it adds up to a lot, because it doesn't - it's the constant alertness, the struggles and leaps of prudence, the prudence of someone who has never in his life felt safe. The balance between the god of good cheer and the god of anxiety is delicate.

I try to follow the windings of his mind. Even to begin to consider the extraordinary phenomenon of human consciousness is dizzying and humbling. In between the microcosms of dust and atoms and the macrocosms of the immensities of space whose silences frightened Pascal there is our realm that seems equally immense and silent, yet full of noise - mostly noise incapable of being interpreted.

The photograph above is from our first years in London, in a small terraced house. Those spiky sub-Picasso shelves and trifles! Tiny pots with minimal spiky plants. A doily.

Two poems from the 'My Fathers' section of Reel. An early start tomorrow. I'll put up another before we go.

My Fathers

My fathers, coming and going

Moustaches and grey homburgs: our fathers were

Defined by properties acquired by chance -

Or by divine decree. Standing behind her

In rooms, on stairs, figures of elegance,

They came and went in a murmur of soft voices,

Objects of bewilderment and romance.

How many of them on the premises?

Some worked twelve hours a day in an office

In the city, some placed bristly kisses

On our brows, some would simply embarrass

Us for no particular reason. Their age

Was indeterminate. They would promise

Anything befitting their patronage.

Were all these fathers one? And was it you,

My father, who pushed me in that carriage

I can’t remember now before time flew

And took her away as it will take us all?

I feel myself flying. It’s like passing through

Clouds in an aeroplane in its own bubble

Of air, a slightly bumpy ride down

Towards a runway as we rise and fall

Above the brilliant lights of a big town.

Their histories and fabled occupations

The histories and fabled occupations

Of their fathers lay somewhere off the map

In provinces lost to their imaginations.

The knowledge they had was fed to them scrap by scrap

And was all they ever needed. The fathers’ presence

Was sufficient. They watched them through a gap

In their mother’s eyes, beyond the fence

Of reason, arriving wreathed in smells of their own,

Some reassuring, others wild and tense

With dangers they had carried home from town.

Their fathers were the seas they read about

But never saw, in which a child could drown

However he might wave his arms and shout

For help. A singular compound figure stood

On the threshold of their bodies and looked out.

Mysterious rodents emerged from the wood

And scurried up the stairs at night to nibble

At their faces. They woke covered in blood.

Their father’s moustache was a scary scribble

Above a friendly voice. His kindness shook

The world out of its endless incomprehensible

Rigor mortis like the closing of a book.

Tuesday, 9 February 2010

Prequel

The first parts of the transcripts of my father's autobiography are ready and I have worked four small excerpts from it into the order of service for Thursday. There will be music for entering and leaving; brother Andrew will play the violin; there'll be a reading of Kosztolányi's wonderful Halotti beszéd (Funeral Oration); the four autobiographical excerpts read by four parts of the family,in two different spots, two excerpts in each; my address (draft written); and C reading one of the shorter poems that I wrote for my father from Reel. We go out to music.

The transcripts are polished up from the verbatim, which is always a complex matter, because once this is done, although there is a voice saying 'I', it is not the voice as spoken, not the person's voice, full of hesitations, revisions, and things in the wrong order: it is literature or, as some would have it, litterachewer. It is not voice but the birth of a possible style. In other words, you lose voice but you gain story. I remember feeling awkward about this when I first started transcribing about twenty years ago (on an old Amstrad, the sheets joined together and perforated), telling myself: if it's facts you want then the edited version is better.

Maybe one could alternate between the two and let the voice just stick its head through the door sometimes. The danger is that we could get Beckett without the genius on the one hand, and Dickens as retold by Jeffrey Archer on the other.

*

Quite exhausted. Late back last night, long time to get to sleep, wake early. To UEA for three meetings, rush home, then start phoning the world -Argentina, Australia, USA, Hungary, as well as various numbers in England. Type up transcript (I no longer have the Amstrad.) Compose address. Ring and talk, ring and talk. Keep modifying order of service.

It keeps you busy, and being busy you don't dwell on anything - except during the writing of the address when dwelling is precisely what is required.

I'll start the obituary / biography once the service is over. In the meantime it looks as though my selected poems in Italian and in German may be back on the menu. But let us not count chickens before etc, or, as one joke's punch line had it, (you can make up the joke that leads to it): The moral is: don't hatchet your counts before they've chickened.

Monday, 8 February 2010

Late back again

Drove down to London to father's house. K waiting for us. It was a warm meeting, one of our warmest. Most of the day spent sorting through papers - a mixture of the emotional and the sensible. There is such a lot to do. We have arranged the funeral for Thursday. A small affair, secular, we'll do the lot ourselves. I have to plan it over the next two days, which won't be easy because of time pressure.

In the evening to Westminster to the Migrants' Centre to do a reading and talk with Mimi Khalvati for Nii Parkes and PEN. Arrived a few minutes late. Of course I said nothing about dad to them - I had had to postpone the session once before. Lovely people - from Bosnia, Eritrea, Sudan, Iran, Iraq, Italy, Belorus, Spain and more. As soon as one begins to talk about poetry it immediately occupies the mind.

And the mind is likely to be very occupied for a while yet. But the biography project will go ahead in occasional bits and pieces.

Pre-publication copies of Fortinbras at the Fishhouses arrived on Saturday.

Now gone midnight.

Sunday, 7 February 2010

My father, László Szirtes 1917-2010

My father died yesterday.He was ninety-two and would have been ninety-three in August. His death was quite sudden after a long period of acute illness from which he seemed to be recovering. I don't want to say very much about it now but I will use this space to compile a kind of obituary for him out of the conversations we shared, particularly after my mother's death. I will illustrate it with a few photographs - and maybe some parts of the many poems I wrote for and about him. I will add parts intermittently, not every day, but it will be a thread running through the blog from now on. I have many tapes, of which I have transcribed about a third.

It is a strange space to be announcing things like this but he wasn't a public man, at least not once we arrived in England. I can't imagine how I would persuade a newspaper to print anything worthwhile. Nevertheless, his life was more than substantial, often exciting in the worst possible way. I have just had a lovely email from the daughter of a friend of his who had met him, in which she says "I remember thinking: this man has a twinkle in his eye when he speaks, as if he finds life an amusing adventure. It was just an impression. I didn't know him well."

Well, yes - my father had no religious faith except perhaps a faith in the power of good spirits. It was more than a matter of principle with him. He clung to good spirits the way others might cling to God. And this super/meta-principle saw him through times when good spirits were all anyone had at their disposal.

It is, to repeat, a strange space for such personal matters, but I am a writer. It is my job to give some shape in language to whatever happens. That shape is, inevitably, a public shape. A blog is a peculiarly floating space - both public and intimate - but it is a space where such things might be shaped. I will try.

Friday, 5 February 2010

Class struggle and class reconciliation - a scene in Márai

I looked him over carefully out of the side of my eye. You could see he was at the end of the road. Old clothes, a shirt he’d clearly been wearing for days, and those glassy eyes behind the glasses. It didn’t need careful examination to see that this man, who had to be addressed as doctor – that’s what I remember – who after the siege on the Danube embankment had left her standing there, as if she weren’t the woman he’d gone crazy over, but someone who once worked for him that he had no more use for - this man was now strictly lower class. And he still thinks he’s superior? I could feel the gorge rising in my throat and had to keep swallowing. I was all worked up inside like I’d never been. If this big shot left the bar now without confessing that the game was up and that it was me who had come out on top… You understand? I was afraid there’d be trouble. He gave me the Lincoln.

‘It’s for three,’ he said. He took his glasses off and polished them. He stared straight ahead in that shortsighted way. The bill said three-sixty. I handed back one-forty. He waved me away.

‘Keep it, Ede. It’s yours.’

This was it. The flashpoint! But he wasn’t looking at me - he was trying to stand up. That wasn’t too easy for him and he had to clutch at the counter. I looked at the one-forty in my palm and wondered whether to throw it in his face. But I couldn’t speak. Eventually, after a good deal of trouble, he managed to straighten up.

‘You parked far away, doctor?’ I asked.

He shook his head and gave a smoker’s cough.

‘I don’t have a car. I’ll use the subway.’

I answered him as firmly as I could.

‘Mine’s parked nearby. It’s new. I’ll drive you home.’

No,’ he hiccupped. ‘The subway is fine. Takes me right home.’

‘Now you listen to me, buddy!’ I bellowed at him. ‘I’ll drive you home in my new car! Me, the stinking prole.’

I came out from behind the counter and took a step towards him. If he refuses, I thought, I’ll knock his teeth out. Because, in the end, you just have to.

It was like the cat got his tongue. He squinted up at me.

‘OK,’ he said and nodded. ‘Take me home, you stinking prole.’

I put my arms around him and helped him through the door, the comradely way only men know, the kind of men who’ve slept with the same woman. Now that’s real democracy for you.

He got out at Hundredth, just before the Arab quarter. He disappeared, like concrete in the river. I never saw him again.

*

That's exactly the way I see John Terry and Wayne Bridge walking off, arms round each other. Now that's real democracy for you.

I have read two female columnists saying exactly the opposite thing. One says men have too much sympathy for JT, the thick bastards, the other says she admires JT's metaphorical balls. What both see - what everybody sees - is the suffering of JT's wife. Wayne Bridge gets no mention there, or anywhere much, except for three of the foreign players at Manchester City who wear T-shirts with his name on, but otherwise he's left blank. As for 'the other woman' - I can't be bothered to check her name - she gets no mention at all. Did she have any idea what she was doing? Was she in no way to blame? It doesn't seem so. No-one is saying so. Case dismissed.

Thursday, 4 February 2010

Faces

In Rilke's The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge there is a passage about faces - I quote here from Stephen Mitchell's translation, one I like very much.

Have I said it before? I am learning to see. Yes, I am beginning. It's still going badly. But I intend to make the most of my time.

For example, it never occurred to me before how many faces there are. There are multitudes of people, but there are many more faces, because each person has several of them. There are people who wear the same face for years; naturally it wears out, gets dirty, splits at the seams, stretches like gloves worn during a long journey. They are thrifty, uncomplicated people; they never change it, never even have it cleaned. It's good enough, they say, and who can convince them of the contrary? Of course, since they have several faces, you might wonder what they do with the other ones. They keep them in storage. Their children will wear them. But sometimes it also happens that their dogs go out wearing them. And why not? A face is a face.

The next paragraph is about those who change their faces too often and too fast. The last one is worn through in a week, has holes in it, and then, little by little, the lining shows through, the non-face, and they walk around with that on.

The third and fourth is about a particular derelict woman on the corner of the rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, who has her face in her hands, but his movement startles her and she sits up frightened, pulls out of herself too quickly, too violently, so that her face was left in her two hands. I shuddered, says Rilke's Brigge, to see a face from the inside, but I was much more afraid of that bare flayed head waiting there, faceless.

*

No one is faceless, of course. Yesterday I was walking down the high street in W, just where the pavement narrows and there is room for a car to pull in and wait. Sitting in the driver's seat was a woman. She was clearly very old but had dyed her hair black or was wearing a wig, a little Audrey Hepburn-ish wig. Her face was thin and fine boned. It wore an enigmatic, childish expression, between a smile and a squint. She wasn't looking at anything particular, but seemed lost in herself. She was an exotic, an extra out of some film noir such as Sunset Boulevard. My eyes were stuck to her face for a second - I am aware of the awkwardness of that phrase but it seems appropriate. I couldn't quite let go of her, and held her for what would have been longer than was decent in the open street, if she had noticed me. She was on the other side of age, as if she had fallen through the mirror and had found herself a child again, but with the same body and the same face. Maybe her strange smile was a sign of her sheer astonishment that this could be at all, that such a thing could happen to her.

Today, in Norwich, I passed the man who has been on the same spot every day ever since we moved to Norfolk almost sixteen years ago. He is a well known local character and has been noted in diaries here and there. He is a busking derelict. All he has is a monkey hand-puppet and an ancient ghetto-blaster on which he plays forgotten, or semi-forgotten, pop tunes. As the music plays he simply waggles the hand with the monkey on it. His own body is loose, loose and floppy as the monkey's. He spends the whole day there - in sun, in snow, in driving rain. It is more than a little surprising that he is still alive. But the reason I mention him is because, later that day, I walked to the bus station and suddenly there he was ahead of me, exchanging remarks with a couple of people, one derelict like himself, the other a bus employee. They seemed to be larking with him. And the oddest thing about this was not him - nor them - but me. I had never imagined the man living somewhere a bus ride away. I had never imagined him with his ghetto blaster and monkey puppet travelling anywhere. His face? It was Rilke's idea of the non-face glimpsed through the lining. Almost unfocusable. But a real face all the same, even in its non-face way. It was the face of a man with a name.

And lastly, today, having got off the bus in W, I passed a very young woman, maybe no more than nineteen. Quite pretty, blonde, short haired. But the way she was walking and something about her face, was much older: older in the way a child looks older, not the way an old person actually looks old. It was as if, under the young face, you could already see the ghost of the older one waiting to show through, the walk of the old woman preparing itself several years in advance in the walk of the young one. For a second I thought of the old woman in the car and put them next to each other, almost transposing one over the other. It was a touch unheimlich - disturbing. Then it was gone. Both of them were gone. There was nothing in the least macabre about this. It was just a passage of time enacted between two women, with the busker in the middle.

Then, of course, there is my own face and whatever it shows, to whomsoever it shows what they think it shows. I sometimes look at it with real curiosity. It's not vanity - I don't think much of it in terms of beauty - but it is, undeniably, there, and it does hold an interest. My interest, at least. Then it's gone. I am not aware of it as I type.

And my mind goes back to when I was about seventeen and thinking grand metaphysical thoughts, wondering which part of my physical self was 'it' - the thing I was. If I lost a finger or had it cut off, would the finger be me, or what was left? Or an arm? Say I lost both arms? Both legs too? Were those lost parts not me - the 'it' - the thing I was? How far can we go before there is nothing left? What is the meaning of the balance in which most of the actual body is missing but the small part that remains still functions? Consider the heads in the basket at the guillotine? Is it the head or the body that is the self, the 'it', the thing that you meet, really meet, as in dreams? Adolescent speculations.

Maybe it is the face, the eyes above all, the thing that looks out at you through them. Maybe that is the thing we encounter in the street, in the car, at the afternoon bus-station, the whole thing moving between face and non-face, just as mine is moving, and always has moved, between the two.

Wednesday, 3 February 2010

Iran

I would say this was an important and brave dialogue, conducted with an understandably pseudonymous correspondent, Darius, currently at Harry's Place. Very much worth following, at a time when we hear of the executions of protesters against Ahmadinejad's regime. Two were executed on 28 January. You can put a face to one in the first link. Nine more have been condemned. I am working from home all day today and will be calling in regularly. Anyone can ask a question.

Sample answer:

...Unfortunately, probably tens of thousands have been killed by the authorities since 1979 and according to various sources 4 to 6 million Iranians have had to leave the country during the last 31 years which, as far as I know, is a world record. Yearly, some 200,000 Iranians are leaving the country, mostly the young and educated part of the population.

It's good to know that sterling folk like George Galloway, and all who associate with him, approve and applaud the regime responsible for all this.

Tuesday, 2 February 2010

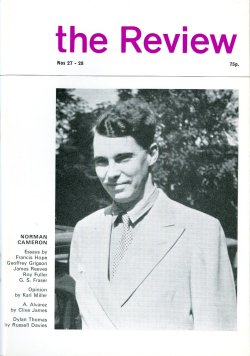

A little more Cameron

Robert Graves's Introduction to the Collected Poems of his late friend, Norman Cameron, says:

We met first at Oxford in 1927; he had gone there from Fettes, and was then President of the Oxford English Club, reading English, playing shove-halfpenny at the Chequers, and occasionally turning out for an Oriel rugger team.... After coming down, he lived near me for a while in St. Peter's Square, Hammersmith; and next, not having done too well in his Finals, accepted a job as Education Officer in Southern Nigeria.