There is a particularly fascinating introduction to this group of poems. It refers to Genesis 15 and the covenant God makes with Abram. The source is Meir himself, from a poem he added to the sixteen. where he recounts that Abram cut his sacrificial animals in two, arranging the halves opposite each other. Having done so Abram falls asleep and "a smoking brazier with a blazing torch" passes between the pieces. Meir proposes to replace the animals with portions of his name in a complex combination whereby:

[E]ach portion consists of two letters and the four letters can be combined in sixteen different ways. In each of the sixteen poems one of these combinations is used to open and close its four lines so that the first word on each line begins with the two letters and the last word ends with them. The reader proceeds through the portions as in "a covenant of pieces"

The obsessive complexity of this process is clearly mystical, right from the dream through to the numbers that enact the covenant. I am not too concerned with the mystical as such, that can remain a closed book for now, but the psychological compulsion of figures, forms and systems is something else.

My own instinctive preference is to establish a relationship with language in which language, with all its accidents and coincidences, is an active, often directing partner. The poem works against the constraints that constantly deflect it into potentially fruitful directions, so, instead of the poet declaring: I have something to say and am saying it, the poet works on the principle that there is something to be said, but what that is is to be discovered. The poem itself is not random or in thrall to its form but it does show an awareness of the arbitrary and unknown. The poet is not in full charge. Language is not passive.

In Meir's terms the poem is the flaming torch that is carried between the half of language that appears conscious and the half that appears arbitrary.

Nothing of Meir's original system is translated here. Even if it could be its significance to us would be lost. A gesture towards the idea of constraint is the best we can do. We read the sixteen poems as individual but connected, lyrics. It is, at the same time, good to bear in mind that these lyrics were not produced in a vacuum, but are the product of formal decisions. One of these formal decisions is retained in most of the translations: the poems were written in quatrains in Hebrew and are rendered as such in English.

*

The first poem addresses God as a royal Guardian, numbered with stars and refers to its own plain and upright words. As with Put a Curse on my Enemy there are many Biblical references, but it is what moves between them that fascinates me. So, here we have:

As my eyes catch light from the holy face

I brighten, wrapped in light, and glow with warmth.

Catching light from a face is a powerful idea that doesn't seem to come with too many Biblical strings attached though I could be wrong. It strikes me as an act of the imagination. Lyrical poems are primarily acts of the imagination.

From light we move to images of water and drought in the second poem but there is a subtle shift to erotic terms in with dew drops of desire the folk are fed, / I too, perhaps, will sip a lover's cup. We know, above all from the Song of Solomon, that religious feeling may be expressed in terms of sexual desire. We may think of Bernini's St Teresa as, by now, a pretty ripe illustration. The ambiguity in the case of the secular reader tends to lean to the erotic rather than the sacred. It is certainly not a puritan way of writing.

From images of thirst it is natural to move to "limpid wine" in the third poem, though the complaint is that there is "no such wine" and that from my sea no clear liquid can be drawn.

From here the imagination begins to take wing. The image of my Love strikes me with awe, begins the fourth poem, and the light of that image is seen sparkling and falling like an arrow-shower. These arrows can wound a heart of truth.

We have now established arrows as one of the elements of the poem. They introduce not only the idea of wounding but of conflict.

The fifth poem speaks of my Beloved, speaks of family and move on to animal imagery.

If pain is a he-goat, then I am a lion

or if as a bullock, then I a wild ox.

This seems a slightly confusing menagerie - the message is 'I will overcome pain' - but the animals are certainly there and appear as with a certain familiarity They are not merely spoken of: they are present.

The sixth poem is a leap. We are reminded of "Egypt's bondage" but expand into "a garment of song", a unique garment entire and incomparable and a place to store it, a palace furnished with courtyard and galleries, which is derived from Ezekiel, nevertheless appears here as a new term, an expansion of the poem. The seventh returns to the idea of the face and preserves the idea of clothing in I'll dress myself with finest speech. Earlier elements are being picked up here as they are in the eighth poem where thirst reappears as a motif working alongside light.

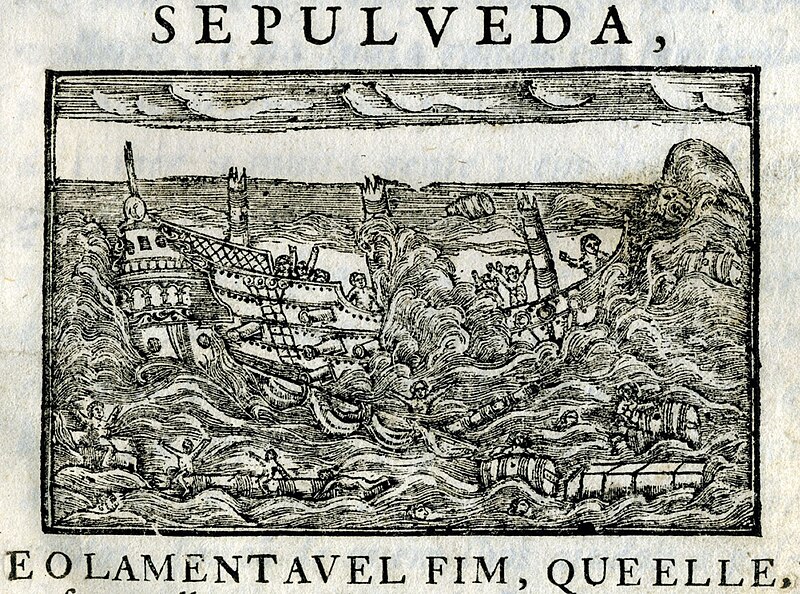

The ninth is particularly beautiful and strikes out in another new direction. The Lord digs a hollow in the heart. The water is now the sea, complete with sea-wind and a ship without decking.

As if my ship lacks decking, he hews off

my inner feelings to serve as shipboards.

Imagery, however complicated, works best when it is conceivable as presence. This is, in some ways, a laboured metaphor but the details are seen with such intensity that their particularity carries conviction. Then the sea is set on fire.

The tenth brings back the arrows, the storehouse, the wounds and the creatures but introduces a wonderful image at the end:

Like a lion he tears us apart,

but our tears he weaves into his shield.

The idea of tears woven into a shield is complex but effective. It hints at something just beyond the solid reach of comprehension but well within its range of vision.

The eleventh poem persists with the sea. The beloved rocks the poet in the sea and covers him with waves, his head decorated with snowy flakes. Ice and hoar-frost will be my ornaments he says. The twelfth talks of purgation and returns us to fire - the words occurs three times in eight lines.

The thirteenth introduces pomegranates while reminding us of wine. It brings in a fowler that ensnares us in his net, before returning to arrows but now bones are being broken too. New ideas appear as part of a developing narrative to the poet but he is always trying to keep the poem together, (I think this is the way most longer poems proceed.)

In the fourteenth Meir picks up the image of decoration this time in terms of corals and crystals, but asks why his soul still seems loathsome. The fifteenth is full of Biblical references as if Meir wanted to re-establish a firm footing in the known, The sixteenth declares the poems to be a coronal of joyful songs and prays that the Lord take pleasure in his precious meditations, these songs of exultation and of awe.

*

That exultation and awe come at the cost of great tribulation. The passage from the light of the holy face, through thirst, water, wine, desire, arrow-showers, shields of tears, animals, splendid garments, palaces, a sea-voyage, a potential wreck, a drowning, ice and snow, corals and crystals, never quite losing sight of the beloved face whose light Meir has caught.

It is the progress of the narrative in terms of imagery that thrills and assures us we are dealing with an individual figure who thinks beyond liturgy. The liturgy is communal: in the sixteen poems we discover ourselves as single creature before the God of our imagination.

*

I want to write one more piece on the book, reflecting on the whole and on its meaning for us.

No comments:

Post a Comment