The Immigrant at Port Selda

I got off at Port Selda and looked out for the harbour

but it was quiet, nothing smelled of the sea,

all I saw was a station by a well-kept arbour

with a notice pinned to a tree.

It said: Welcome to Port Selda, you who will never be

our collective unconscious nor of our race.

This is the one true genealogical tree

and this the notice you will not deface.

It was beautiful there. It was Friday in late

autumn and all the birds of the county sang

their hearts out. I noted down the date.

The sun was shining and the church-bells rang.

A few weeks ago, during the Words, festival someone was reciting Betjeman's famous poem about Miss J Hunter Dunn and it was remarked to me how English that poem was, and that I could hardly be expected to recognise the specifically English experience to which the poem referrred. I understood what the speaker meant, though it was an odd moment in many respects. He was right, or rather I supposed - and continue to suppose - that he might be right, because, after all, there are levels of being one cannot vouch for. I suppose it was an odd moment to draw that line between what constitutes Englishness and where I might be supposed relative to it.

It took me back to another occasion in my schoolteaching days some twenty or more years ago, when the conversation turned to cricket in the staff room, and having grown fond of cricket I venture an opinion on style. I had clearly taken the others aback, since there were raised eyebrows and a little surprised looking, as though there were objects within the sanctum of consciousness of which I could not be presumed to speak.

I don't argue that this was specifically English, since it is quite likely that anywhere in the world you would find such sanctums, those spaces of shared being informed by the experience of generations. It is right that visitors should respect such spaces and that, occasionally, there might be family business at which it might be proper for the visitor to withdraw. That is if one had somewhere to withdraw to. That isn't always the case.

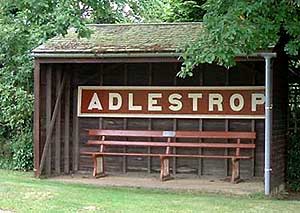

Hence the poem. I thought of Edward Thomas, and particularly of his poem, Adlestrop, which conveys to me something related to, if not the same as, Betjeman's poem. Betjeman's poem is a social creature inhabiting a social field. Edward Thomas's is about something deeper and yet proceeds from something, a sense of place, mood and language, that might be felt more intensely by the native Briton. Looking at that photograph in a recent blog of Adlestrop, the name, as Thomas says, I note, as others might have done for all I know, that it spells Port Selda backwards. A port! The very place an immigrant might arrive at. So the poem.

7 comments:

Or this, which I wrote in 2010. It copies the original's syllable pattern, but in sentiment is rather its opposite.

Port Selda

I'm not sure. Maybe Egypt, or

Greece. Not backward, just ethnic. I

remember waiting for a ferry,

men mending nets, picture-book sky.

An octopus pulled itself from

its bucket, plopped like a mop.

Then I saw her, her bare shoulders.

A boy beside me paused, looked up,

whispered 'Mista' as she stopped too,

her pose so sweet my mouth went dry.

On makeshift tables men shared food

ignoring her as she walked by.

And I'd forgotten my camera.

The boy raised his palm, asked 'Mista?'

She'd gone, and my ferry was late.

Or maybe it was India.

That's very nice. Welcome, Tim, to the unrivaled facilities of Port Selda, which may possibly be in India. Or Egypt. Or Greece. An Englishman's home is his Castile.

The Miss J Hunter Dunn poem (and much else by Betjeman) leaves me rather cold. I am an English person born in England to English people. . .and I do not recognize that world as my own. I see that some may do so. It is a poem concerning one specific view of England. I know it's satirical, but it satirizes something I hardly recognize.

Am put in mind of the (probably not satirical) John Major speech which eulogized, what was it ? village greens and cricket and elderly spinsters cycling to Holy Communion. Not in MY world, John !

Yes, it's an upper-middle-class, southern English outlook: it wouldn't surprise me were the bulk of modern English people to find themselves at a distance from it. But that doesn't lessen the force of George's point, because those who do feel a kinship with the poem are no less territorial than working class people who go on about how no outsider could understand their world or have some part in it however small. But there's an instinct to feel, isn't there, that what Betjeman was writing about should be considered everyone's place and property, however that might be worked, part of the universal inheritance. The same instinct stands up to defend claims of working class exceptionalism.

The problem was always, in any case, that both Edward Thomas and John Betjeman were capable of describing what, for most people, had just slipped out of view, an England that must have been frustratingly elusive as early as those very reigns-of-Edward-and-George times they puported to record.

It makes me wonder whether at the backs of the minds of the cricket men who evince such surprise is the dulling knowledge that what they claim to know and be part of, they came too late for and never really knew themselves and that there will always be something uneasy and ersatz about them as they put the brave face on it.

There are of course many Englands just as there are many Frances and Germanies - even Hungaries. I am aware that Betjeman's world is, as James says, a middle class, between the wars-and-just-after England and that it wasn't everybody's. In my university lunch hour today I was watching YouTube clips of the old Alec Guinness Tinker Tailor (infinitely superior to the new movie) and was thinking that was England too, as were Ealing Films and Sid James and Wigan Pier and Southend and Akenfield. All these Englands existed. Each individually is a caricature - it is when they are taken together they form a proper entity. And, yes, John Major's England too is a piece of that since he was only following Orwell and Auden in talking about warm beer and cricket and old ladies on bicycles.

And there is so much more. The Sun and The Guardian are part of it. The pub and the queue. The perfidy, the icy politeness, the dullness, the cheeriness, the stoicism, the bloody-mindedness, the B&B's and the whole landscape Martin Bell catalogues in that splendid poem, Winter Coming On. The England panther is thinking of is there too.

And I have genuine love for this curious compound of caricatures. Because the odd thing is that when you put them all together, despite the contradictions, it's still one recognizable place called England.

My beef, which isn't really a beef just a piece of wistfulness / ruefulness, is not with Englishness, but with any defined sense of belonging that is by its very nature exclusive. I envy that and miss it in some way or, to put it another way, I understand what it must be to those who possess it, and think it perfectly natural, virtuous even, at least in its open aspect.

It's just that there are limits ,and people occasionally remind you of them. It is as one rather gross school housemaster told me some twenty years ago when he was first appointed. 'Your name isn't too sweet around here,' he confided. 'That Szirtes, they say, all very clever, all very friendly, but, a bit, you know, Hungarian'. I think I am remembering that correctly. And I suspect it still goes on under the skin. In the best possible taste, of course. And it doesn't hurt. Especially not when it remains under the skin.

As Spike Milligan said when an army sergeant confronted him with 'What are you doing here, you horrible little man?' 'Everyone's got to be somewhere.'

George, I might be commenting too late by now, but was the initial poem at all anything to do with this recent (and fascinating) NS article on the original Adlestrop poem?

Thanks for the NS link, James. I have been reading the Matthew Hollis book. This is such an interesting issue I am going to write a brief blog post about it.

Post a Comment