After a hundred years of solitude we emerge into the bright lights of the movie palace to see Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy in Norwich, where for an extra few quid your comfortable chair provides massage. Actually it doesn't but there are 'luxury VIP seats' at the back that might one day provide such a service. The trouble is the Castle Mall Vue (Screen 3) doesn't believe in much air conditioning, or didn't last night, so the hot, unseasonal evening started in a fug of warmth with the stale smell of day-old bodies.

Not inappropriate perhaps. The 1974 book on which the film is based is the insider, John Le Carré's fictionalised version of the Cambridge Five, the infiltration of MI5 by the Burgess, Maclean, Blunt, Philby and Cairncross group. The book is a classic of the genre. Le Carré is a real writer.

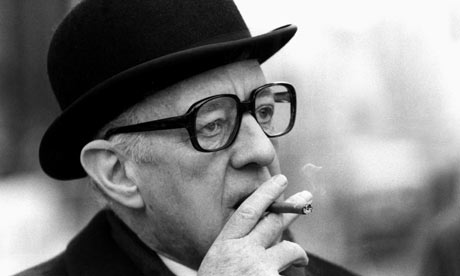

As for the film it has a good cast though I remember watching the 1979 television series over seven episodes with Alec Guinness and an equally strong cast that left a very strong impression, (all here), especially Anthony Bate, Bernard Hepton, Ian Richardson and of course Guinness himself who was marvellous in the role of George Smiley.

I don't think the film compares well. Firstly, most importantly perhaps, it was made over twenty years after the world in which the story is set collapsed. The television series was right in it: in so far as the tension between the West and the East still existed it was current affairs by other means.

For better or worse, chiefly worse, the distance in time has turned the story into something else: into evocation, mood and design.

Very well, the distance in time can't be helped. It also can't be helped that this is a feature film (c 2 hours) of much shorter duration than the series (c 6 hours) so character, incident and complexity can be indicated only in shorthand. This is true of all books that become films of course, but here the comparison is with the television series. Movie language is not the same as TV language and the episodic nature of the TV series left the viewer with less sustained gloom and more suspense from week to week.

Nevertheless the film is still a fine piece of contemporary story telling, which means rapid cuts from place to place and from time to time, sometimes so rapid and ambiguous that the audience has to lag slightly behind and take things on trust. (Whenever anyone tells me that modern poetry is difficult I am tempted to ask them to think carefully about almost any contemporary movie. The games with time and place are more complicated even in the simplest of them than in most poems.)

It's fine story telling but with limited means, whose deficiencies must be supplied with, er, evocation, mood, and design.

So the film is shot in very low intensity light verging on grey. There were no sunny days in the world of the Smileys. The world of the secret services is grey so everything must be grey. Yes, it resembles bad seventies photographs but we have to look at it for two hours. It's like spending a very long weekend with a long lost cousin of Luc Tuymans.

As part of the general greyness it is carefully arranged that every secret meeting should take place in a disused factory or a bare room. Not only that but every secret agent must work in conditions of utter dereliction.

In such circumstances the only proper human response, the film tells us, is pained silence. The dialogue is mostly monologue. People ask things that their interlocutor doesn't answer. They look into the pained air with a faintly pained expression. Smiley, despite his name, does a lot of pained looking. He's brilliant at it.

Against this background the characters stand little chance of becoming characters. They become instead a function of evocation, so though we recognise the underlying gay affairs, the complex machinations of the various figures as exemplified in Control's chessboard, and the tension under which everyone is living, we don't really know who they are. Gary Oldman is sterling as Smiley but apart from being traumatised by his wife's affair with one of his colleagues, we don't know what else is bugging him. He never has a chance to convey that to us. Pained silence is his best card and since he is our central character it simply isn't enough. Alec Guinness had a proper hand of cards and was owlish and human: Oldman is like one of Comntrol's chess figures.

Not Oldman's fault. And I shouldn't whine too much because, in the end, I enjoyed the film as design-narrative. The cuts, particularly the cuts, and individual frames were in some way compelling. The film is - God forgive me! - well made. I asked C before we went in what mark she anticipated. She said 9, I said 7 so we agreed on 8. While the film was on it chugged along at a steady 7, but as soon as we went out and started talking about it, the mark started dropping. Very well, 6- isn't much to drop to, and it's OK, and worth seeing.

The same surely cannot be said of any of the films being trailed before the feature started. I hate and despise trailers. Nothing puts me so off a film as its trailer to the extent that I don't think I have ever seen a film on account of its trailer. I have avoided every one of them. Hence the hundred years of solitude. Maybe that is what was not quite right about Tinker Tailor - it was a very good class of trailer for something else.

1 comment:

Hate trailers? Me, I hate to miss them. The best bits of any movie are excellent for deciding what you don't want to see. If only life had trailers, it wouldn't take nearly so long to realise where one has gone wrong. Anyway, thank you for the review. It quite cheers me up after finding the film sold out the other night.

Post a Comment