Blake said: Fun I love, but too much fun is of all things the most loathsome. Mirth is better than fun, and happiness is better than mirth. True, happiness is better than fun, and much better than directed fun, or enjoined fun, or expected fun, all of which are anathema. The words Let's have some fun now, always carry a threat of some sort. Because there are rules for having fun and, usually, they are the rules favoured by bullies.

But fun, meaning the ludicrous, the light-hearted, the throwaway, the giddy, is welcome, especially perhaps to essentially serious people. Sometimes life seems a very solemn affair, sometimes it seems fraught or even tragic, but, to reverse Blake, too much solemnity is loathsome too, in fact at times it is positively intolerable. Gravity is for grave occasions.

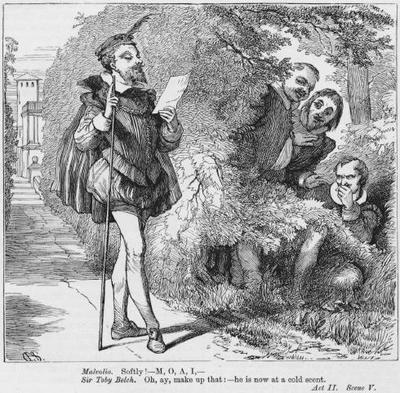

I think of poor Malvolio (yes, poor in some respects). He makes that officious speech late at night, where he admonishes Sir Toby Belch, who can himself be something of a bore. It is what he is hanged by:

My masters, are you mad? or what are you? Have ye no wit, manners, nor honesty, but to gabble like tinkers at this time of night? Do ye make an alehouse of my lady's house, that ye squeak out your coziers' catches without any mitigation or remorse of voice? Is there no respect of place, persons, nor time in you?

It's a reasonable enough speech at that time of night, if priggish, and many of us might make it in such circumstances. But underneath it lies a character defect of some moment. As Maria says:

The devil a puritan that he is, or any thing constantly, but a time-pleaser; an affectioned ass, that cons state without book and utters it by great swarths: the best persuaded of himself, so crammed, as he thinks, with excellencies, that it is his grounds of faith that all that look on him love him

It is not so much what he does on the occasion but the affectioned ass he is at all times that damns him. Sir Toby Belch's answer (which would be Jack Falstaff's answer too) is what appeals more to most:

Dost thou think, because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?

Cakes and ale are not vital to life. They are frivolities we become addicted to.

*

I am addicted to some frivolities.

I love puns and quips and those occasional veerings into nonsense when sensible language goes off-piste vanishing into a snow-covered forest to emerge again down the clear slope of the talking village below.

For that reason I will sometimes accommodate the helplessly cute, the awkwardly sentimental and the extended joke providing there is delight in it. I hope to know what Mr Bennett meant in Pride and Prejudice when he remarked to his daughter Mary: That will do extremely well, child. You have delighted us long enough. Mary's singing had outstayed its welcome, as will the welcome accorded to nonsense.

And yet, in a solemn, indeed murderous world, comedy without thought of satire, without even too much awareness of the philosophical aspects of the Absurd, might be given a little more space: not the highly deliberate, calculating sort of comedy that adorns itself with a capital C and slumps all over Radio Four, but the accidental almost-grace that fails.

There was a book back in 2006 titled Is it Just Me or is Everything Shit? There were, in theory, two answers to that, but only one of them was being argued. Frivolity argues the opposite corner. A modicum, a sprinkling is ideal. It serves a reminder that delight exists, that out beyond us and our self-importance there are solar systems and galaxies and immensities that are magnificent and terrifying and, in human terms, absurd.

It is perfectly obvious that we are not, like Malvolio, 'crammed with excellencies', but we do possess some excellencies, yes we do, almost by accident, and that is the funny thing.

1 comment:

'out beyond us and our self-importance there are solar systems and galaxies and immensities that are magnificent and terrifying and, in human terms, absurd.' And this is something, I think, that poets know by instinct - but only the greatest can put both the absurdity and the magnificent terror into a human context.

Thank you for this insight, George.

Diolch yn fawr!

Jeni

Post a Comment