Some more about the family.

I was born in Budapest, in a small clinic in Ferencváros, the IXth District, in 1917, the first child after my parents' marriage in 1916. Two and a half years later came my sister Lili who now lives in Argentina, and two and a half years after that, my little brother Endre, who was killed in the holiday accident, buried under a pile of sand near a railway yard.

My father was born in 1886, my mother in 1893. I remember very little of them at that time. They were both thin. He looked like me, was never very elegant, wore a trilby and tie, dark suits and went clean shaven. He had dark hair, no moustache, a big nose - just like mine - and had had a bad operation when his was sixteen or so that left a two-inch scar under his arm. He was one of five children, with two brothers and two sisters. The two brothers went to grammar school, the gimnázium, and became educated men, unlike my father. The rest of the family looked down on him as a result. He got a job in the shoe factory instead and became a cutter, cutting the leather: quite a skilled job but poorly paid.

His sisters were never married and lived with their parents. They were called Riza and Ernestina, who was known as Tini. It was Riza and Tini who really brought me up. Riza, who was born in 1884, lost her only real love in the First World War and never got over it. She sacrificed her life to look after her parents. She earned a bit of money sewing at home or helped my mother when she had too much work. She was a dear, gentle woman. Tini, the plainer of the two sisters, looked older but was younger. She was resigned to doing the housework with my grandmother. She walked badly but loved shopping at the local shops. She and Riza would buy half a kilo of bread every day and 5 decagram of butter. There was usually a half kilo of cooking fat, and milk, of course, because there was no milk delivery then. Tini would carry the milk home in a jug each morning. Milk came in churns and we had to use it all up as there was no means of keeping it cool. Richer people had a kind of refrigerator that worked on ice, sold by icemen, which consisted of a tin compartment equipped with a tap through which the melted ice ran out into a bucket.

Their flat was in Eötvös utca [utca means street in Hungarian, you say it ootsa!]) and consisted of two rooms, a kitchen, a little hall and an outside toilet, all on the first floor of a four storey house. There was no bathroom.

The rooms were dark, the windows looking down on the yard rather than the street. The main room served as both dining room and bedroom. There were two single divans in there where my grandparents slept. All the walls were painted a light colour to compensate for the darkness - a light cream-yellowish colour. The furniture was old and dark though: a dining room table with chairs and a sideboard, all of dark wood. In my aunts' bedroom there were two single beds and a divan for me.

I didn't mind the arrangement, in fact I loved it. I would spend days with the three women - grandfather being out at work - and played football with friends in the same block, kicking the ball along the galleries, or table football, using buttons when we were indoors. Or we might go out to a small park nearby that was all earth and no grass, but had a few swings. There some places like this in Budapest, often poorly kept. One of my friends lived opposite us and we remained friends till the war. He was killed in Russia.

I was pampered and spoilt, regarded as the little bright chap of the family. School started when I was six. It was half-day school so I'd arrive home about one o'clock and every day my aunties would go down to the baker's and bring back a piece of pastry or mignon for me when I returned. They were very proud of me because I had good school results. My name was printed in capital letters in the yearly reports of the school.

But when I was twelve my maternal grandfather, the one who told me the Bible stories and who used to be a painter and decorator, died. That made a terrific impression on me. It was my first meeting with death. One day somebody is talking to you, the next he's not there. I attended the funeral but I couldn't cry. I didn't really understand adults crying.

My paternal grandfather never talked much about the Bible, but he would visit every day when I returned to my parents for parts of the school holidays. He always brought sweets with him. He'd buy soft creams and put them into his pocket so by the time he arrived they had all melted into a great mess in the brown paper bag. But he presented the bag to my sister and I with ceremonial affection. 'Look what I have brought for you, my dear Lilike and Lacika'. It was nothing but crushed cream and wafer.

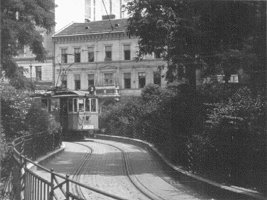

Then the dear man was hit by a tram. He was about seventy-seven at the time. His skull was broken but he recovered and lived for another year and half before dying. I think I was fourteen. Being hit by a tram was the most common accident since everyone used trams. People hung off them like grapes. I was at home when it happened. A policeman called to say my grandfather had had an accident and been taken to hospital. Everyone rushed to be at his side but I was left at home to do my homework.

The accident with the tram brought with it some compensation that would arrive weekly in an envelope. There would be a scramble between my grandfather and grandmother for it. 'Who had to lie down under the tram for it!?' my grandfather would protest.

It became a family saying whenever reward of any kind was the subject. 'Who had to lie down under the tram for it?'

No comments:

Post a Comment