Here then is the Guardian blog as I first wrote it. I would like to think further about some of the ideas in it, and maybe consider some of the comments on the Guardian site.

"Why do novelists so fear the death of the novel? Poets don't fear the death of the poem," responded Jackie Kay to the debate following China Miéville’s keynote speech about the future of the novel.

There is constant and loud debate about the death of the novel - Will Self was voicing his doubts about it only this week - and less debate (though not none) about the death of the poem. The true distinction however is not between novels and poems, but between story-telling and poems.

The novel is a specific but not fixed form of story telling in the same way as the romantic lyric, or the sonnet, is a form of poetry. The two deep patterns are story and poem.

There are two essential instincts in engaging with the world through language. The first is the cry of encounter linked to the desire to name; the second is the evaluation of options as a result of the encounter.

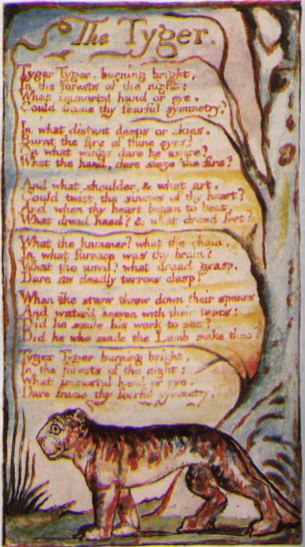

The Tyger is a poem by Blake. Tiger! Tiger! is a story by Kipling introduced by a verse. The first doesn’t tell a story but offers us a burning presence in the imagination: the second doesn’t dwell on presence except in so far it is an aspect of consequence. Consequence is vital. To take a very brief passage from Kipling:

Buldeo was explaining how the tiger that had carried away Messua's son was a ghost-tiger, and his body was inhabited by the ghost of a wicked, old money-lender, who had died some years ago. "And I know that this is true," he said, "because Purun Dass always limped from the blow that he got in a riot when his account books were burned, and the tiger that I speak of he limps, too, for the tracks of his pads are unequal.".

“Because Purun Dass always limped”. In stories there is always an implied “and then” and a “because”. There is neither a ‘then’ nor a ‘because’ in Blake. No-one reads a poem like Blake’s to find out what happens in the last line. The end is the beginning

There are various forms of narrative poem. We can deploy the old categories and talk of epic poems, discursive poems, and dramatic poems as well as lyrical poems, but there is something significant in what Poe argued, that longer poems are essentially linked short poems, a series of flashes.

Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of The Ancient Mariner’, is a ballad and therefore a story. But even here, where story would seem to be the point, it is not the story that registers most deeply. It is tableau after tableau, each with its own presence: the encounter with nature and the imagination. The Mariner himself is thin as a character, a semi-transparent vehicle for a series of encounters with the world.

The poetry is where the presence burns more than the narrative drive.

Ideas of character and consequence are at the heart of the novel, and inform the story. Forster sighed about having to impose stories on characters but he felt obliged to, nor might Oscar Wilde’s Miss Prism have been entirely wrong in suggesting that fiction meant that the good ended happily and the bad unhappily: happiness and worth are issues in novels to an extent they are not in poems, and even the great Modernist novels in which voice and character seem almost interchangeable, offer choices and links that prevent the book from breaking up into a series of poems. We seem happy to enough to read passages from Homer, Virgil, Milton, Pope and Wordsworth: it would seem wrong to know the great novels through this or that passage.

There is no sense in arguing for the supremacy of the poem or the story: both are equally important. The poet and the story-teller co-exist in human beings, though not to the same degree in individuals.

The novel being a highly specific, on the whole stable, form of story telling, assumes a great deal about the reader’s relation to the world and language, and it is quite possible that such a relationship will demand - may already be demanding - a different psychological form of story-telling just as it might demand of poets a different construction of poem.

The novel may be dying - it does get to feeling a bit tired at times - but the instinct to story does not die, nor does the instinct to poem.

No comments:

Post a Comment