Of the two exhibitions I preferred the international Things are Drawing to a Crisis (a slightly odd translation of the Hungarian Válságjelek, which is literally 'Signs of Crisis'). The accompanying newspaper-like handout begins by comparing the current world financial crisis with that of the Thirties, and while that is, I suppose, a natural enough analogy, it seems - on current evidence at least - too far fetched.

But this exhibition is about the crusading, social (and generally socialist, often specifically communist) activities of various photographers to document poverty and unemployment. There is a sentence of Alan Sekula's on the front page to the effect that " looking at documentary photography as a work of art is running the risk of making the subject almost invisible and taking the photo for an impression of the photographer's sensitivity and personal vision."

I fully agree it runs the risk, though I can't see how the risk can be avoided, and it is unlikely, I suspect, that the subject ever becomes completely invisible, as it might, say, with painting, where the artist is fully expected to be presenting a personal vision. There is no way of obviating the observer, or detaching him or her from the observed. There is the whole business of selection to start with - the photographer goes somewhere for reason, takes a lot of shots then selects from the contact sheet, according to certain criteria (in the case of the current exhibition it might well be Constructivist approaches to composition).

However, the subject stands in a special relationship to the observer (and consumer) in photography, because - and I have often argued this before - we the consumers, as well as the photographers, are conscious that at the split second light enters the camera there is an uncontrolled mechanical process of the kind painting doesn't offer. Which is one of the reasons why photographs may be admitted as records of events in court while paintings or, say, poems can not. The only way that I can see that a painting (or a poem) might be used as legal evidence is in a case where the painting or poem is itself directly the result of or producing some possibly illegal action (eg Is this painting what you say it is? or What is the seditious effect of this poem / painting?)

I don't want to argue all this now. It's only a blog-post after all, not an essay. Enough to state I thought this a marvellous exhibition in which formal values were at the service of a never-forgotten humanitarian cause. I could never overlook the sheer encounter with the real people at the far end of the lens. Every one was person first, compositional element second.

Who was in the exhibition? Well, a lot of Walker Evans, whose work I already knew and had in fact written about in the past, but the ones that move me most were Theo Frey, John Fernhout, the Hungarians Eva Besnyö and Kata Kálmán. A good half of the photographers were women.

Theo Frey: Radrennbahn, 1935

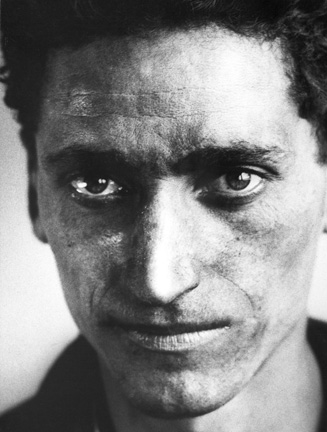

Kata Kálmán: Ernö Weisz Fabrikarbeiter, 1932

I'll try to get actual pictures up as soon as I can (best I could grab above), but it is impossible to look at these photographs and not think the figures shown dignified even in degradation. There are beautiful faces, plain faces, strong faces, weak faces, defiant faces and broken faces - and there are the faces of children as bright with life as the young of the healthiest, often children labouring in field and mine. They are all breathing the same air as the photographer.

And having noted and been moved by the self-evident dignity of the faces and bodies, however thin or broken or breaking, it then becomes perfectly natural to conclude that the photographers were right to align themselves as they did politically. Why after all should these dignified people be so much poorer than those others sometimes glimpsed passing by on their way to a theatre or cafe? What earthly reason can there be for such disparity?

It's really that simple.

In that way the polemic of the photographs is subtle, valid but powerful. I don't think we would necessarily think this after seeing an exhibition of paintings, not in the age of photography anyway. We know that there existed a moment when precisely these people, stood in those precise places, and were as alive then as we are now.

2 comments:

When I become dictator, I'll insist that beside each print in an exhibition be hanged a complete set of that film roll's contact prints, signed for authenticity by Alan Sekula. And yes, digital photography would make for enormous contact sheets, but dictatorship always tends to absurdity and gigantism and mine would be no different.

I've a book here with reams of Walker Evans's contact sheets in it, and in amongst those there's only the odd "Walker Evans": the rest are sharecroppers or parked cars or morning drinkers or women glaring at the anonymous, inopportune photographer.

I'd love to see Lartigue's but I'm afraid that it would be like one of those poets' notebooks that you read and realise, with sinking heart, that they're all that good.

I know Walker Evans's contact sheets - or some of them. There is an early poem of mine, 'Mare Street', based on one of his photos.

Gorgeous photographer.

Lartigue is also a deliriously lovely photographer - as happy a photographer as ever the world allows.

Post a Comment