The ever inventive and unruly Max Fleischer, all wobble and flicker, all romp and sheesh!

Sunday, 29 April 2012

Saturday, 28 April 2012

What politics sounds like in Hungary - a translation

János Lázár is a leading figure in Hungary's governing Fidesz party. He was being interviewed by András Pugor for the weekly 168 Óra. I translate a few chunks.

The interview begins by exploring the effect of the plagiarism scandal of ex-President Schmitt that Lázár dismisses by suggesting that the claiming of false doctorates is common so nothing to make a fuss about. Schmitt was a good guy, just unlucky, unlike other people.

It then moves to the newly appointed President of the country, János Áder. Why, asks the interviewer, should Prime Minister Orbán, having lost a highly manipulable supporter, immediately appoint another very manipulable supporter to this key constitutional post. The answer:

Being a member of a [particular] party is not an obstacle. One may still be honest, correct, and capable of representing the people as a whole.

The interviewer wonders how such a figure could claim to represent the whole country.

Maybe he doesn't want to. Once elected the President is officially independent. It's his business how he goes about representing national unity...The President of the country should be someone with values but, at the same time, capable of understanding other people's values. Áder fits both these descriptions.

Why not appoint someone, the interviewer asks, who doesn't simply listen to what Orbán tells hims at night so that he might turn it into law the next morning?

You can't possibly say that about Áder, a figure regarded as the Charles Bronson of the angling world, not one of the elite but a man of the people...[On registering the scepticism of the interviewer] I'm sure you'll come round to him in due course.

The interviewer challenges Lázár about parliamentary procedure, accusing Fidesz of foul play, aggression and contempt of the opposition, using individual amendments to block the possibility of agreement. He asserts that the amendments are often at the last moment when there is no chance of proper consideration. He gives as an example how a bill about MP's pay is then used to rush through measures about electricity and gas, and how another about water manages to outlaw a doctors' strike. Lázár doesn't quibble about the details simply answering:

Thank God parliament is full of representatives whose job is to write laws...If we make a mistake we put it right. We shouldn't forget that there has been an acceleration in legislative procedure. There is some justice in what what you say but we need to take quick decisions.

What about the willingness of two ministers of state to engage in dialogue with representatives of Jobbik? [The Wiki entry has clearly been modified by Jobbik itself, but it's interesting to see how they would describe themselves. Jobbik denies being a fascist party, of course, but if it walks like one, talks like one, refers to the same flag as the wartime Arrow Cross, etc. Go compare, as they say. It is most certainly fascist, down to the military wing.]

Most unfortunate. The electorate voted them into parliament nevertheless a party with a two-thirds majority should not regard such a party as fit for dialogue. Not with the Jobbik whose representatives have made the kind of statements we have heard these last two weeks. [He means the strongly anti-Semitic speeches, references to the blood libel and the questioning of the Holocaust].And did you say as much to your colleagues in the party?

I did.And?

They didn't agree with me.

We now move on to the issue of Lázár's own personal attacks on András Schiffer who was the leader of the LMP, Politics Can Be Different, parliamentary group. The interviewer accuses him of being 'extraordinarily crude' on account of Schiffer's parents who had held positions under the pre-1989 Kádár regime.

[Such attacks] are only a problem in our society. They are everyday practice in the West.

But, complains the interviewer, they don't attack the son on account of his father.

That's not what history shows us. Someone who was a beneficiary of the Kádár system, enjoying all its advantages, should not go around telling people how bad that system was. History must be on the losers' side. Schiffer's family benefited from the old system. This is a matter of credibility.But why not discuss Schiffer's proposals [rather than make ad hominem attacks]?

Unlike Schiffer I was in Vásarhely revealing the names of seven hundred agents of the state with all the risks that entailed. I didn't make a big noise about it. Schiffer tried to make political capital out of that. If he does that he shouldn't be surprised when he is criticised...Schiffer's case shows how the left-liberal elite will not tolerate any opinion other than its own. [He then launches an attack on 'the sickening lies' of the 1989 change of system that, he asserts, failed to deal with ex-agents of the state]

*

Etc etc, ad inf. The everyday political life of a healthy country.

WebRep

currentVote

noRating

noWeight

Debatabilities in Cambridge

|

| Not of Thursday's debate |

All Thursday I was in Cambridge at the Cancer Research Institute, listening to debates and eventually judging one. The day is part of the Debating Matters programme organised by The Institute of Ideas for whom I had engaged in a number of panel discussions in the past. They have all been great admirable gallops through a central question addressed by those on the panel, not with a view to a vote but simply to articulate thoughts as clearly as possible.

But this was a competition for schools who had got through qualifying rounds to arrive at this regional stage. It consisted of formal debates with strict rules, a firm proposition with proposers and opposers, a panel of judges who ask questions and sum up, and an audience that is invited to put questions to the teams.

Schools arrive with teams of which two students are allocated to one debate, two more to another and so on.

Why debate? Shouldn't we all just be getting on with each other, coming together on common ground? Wouldn't the world be a better place if we were just nice to each other?

The point of adversarial debate is to examine an issue thoroughly through criticism. At its best, it is not about scoring personal points, bullying, or finesse but about the proposition itself and what the proposition entails. Adversarial debate proposes that by fudging issues we conceal them. In matters of law - and few people are against law - we are either guilty or not guilty as charged. We depend on one side to state every possible argument for, the other every possible argument against.**

The point of consensus is that we begin by regarding each other as potential partners. At its best it foregrounds our common humanity and by establishing relations looks to overcome difficulties through the willingness to overcome them. It assumes good will and may, by assuming, actually generate goodwill. One has to start somewhere. (The recent attempt by an Israeli family to send love to Palestinian families is one possible way of starting, as is the Barenboim-Said West-Eastern Divan and one would have to be very sneery indeed to dismiss such things as meaningless gestures.)

The weakness of consensus is that it looks for agreement and steps round potential difficulties that might prove fatal.

The weakness of the adversarial is that one may present a very weak argument for a strong case, and vice versa. But formal debates are sparring rather than boxing. No actual harm is suffered by either the cause or the parties in debate. It just makes both think harder.

Some impressions

The first three-minute statements were often the least interesting. The basic position was set out in 1, 2, 3 manner by the teams, a little like building with big bright blocks of Lego, sometimes coolly, sometimes with passion. Passion is good. The very idea of the debate is bound to be adversarial in nature. The point of adversarial argument is to examine a case more thoroughly than you could with consensus in mind.

The fun really begins after the initial speeches have been made. This is where background reading and thinking on one's feet become important. Blocking, striking and dancing are the required skills. It is where the most able and best prepared can shine.

In the first debate - one between girls in favour of the Olympics and boys against it, it was amusing to see how the girls in their self-descriptions played it very straight, while the two boys played enigmatic code games, one saying practically nothing, the other spouting self-mocking nonsense. Neither boy could afford to be himself. As it happened their case warmed up nicely the trouble being that it was based entirely on cost and though the girls' case reached hyperbolic levels - it was worth any price, however high to have the Olympic Games - people do on the whole prefer to make choices, when possible, or so they would say, despite of money constraints.

The second debate was about opting out of organ transplants. Probably a better debate, chiefly about autonomy versus social good, decent use of figures. The boy against opting out eventually won the finest individual debater though his team did not make the final.

My own debate was on a more complex issue that did not require a commitment to action, simply an agreement or disagreement with the proposition that resources were running out. You can quote statistics either way. If the question had been about our obligations either way there might have been something at stake. The debaters did well with what they had in front of them - it was a tough issue to be given - but it didn't make for lively argument.

The final was between two teams of girls, on the the rejuvenation of political protest through social media. It is not a very difficult case to make since there is plenty of evidence that FB and Twitter had contributed to the organisation of political protest, and the counter-claim that last summer's riots were just not political isn't enough. A better line of argument might have been that while social media get people together and encourage a gang mentality, they don't go much further except as links to read more substantial pieces of writing that are published in the press or books.

And so on. This is getting to be a tediously long piece, but I found the event cheering and entertaining. Intelligent people are perfectly capable of lazy thinking. You can't afford to be lazy in such circumstances and the exercise showed intelligence in action.

** I have sometimes thought of organising poetry workshops on adversarial lines with one student to level every possible criticism at the poem and another to praise all its possible virtues, guessing that more of value might be said, but this is psychologically a very difficult process in an area so concerned with subjectivity and vulnerability, and in the end the best course is often to chair the discussion as judiciously as possible.

Wednesday, 25 April 2012

It was the best of times

We were fabulously wealthy. We rode horses in our sleep. Our walls dripped art. We knew everything & nothing. It was ours to lose.

*

We were in heaven in a smart car. The streets saluted us as we passed. Behind us, like a honeymoon trail of trash, the big stores, grinning.

*

Our servants were invisible. They ran about with heavy trunks containing their own lives. When we tipped them they glowed like embers.

*

Sometimes we wanted rain. We knew the right people. They'd come running with their dry excuses. It was the excuses that we really wanted.

*

For all our wealth we were unhappy. The sex was bad but the service was excellent. Our salt cellars were pure gold but our feet were tin.

*

We dispensed largesse between meals. Crowds came to our funeral. They were sporting buttonholes of dead flowers. We fed them caviare

*

Our dreams of avarice were spectacular affairs. Mountains moved. We had a fleet of empty cars. The music under the streets was perfect.

*

Shari found herself in India. Martin was in China. We were in several places at once at the centre of the earth. We paid and left.

*

We had people to do things for us. We paid them fortunes. When we woke we were those people. We led full and interesting lives on hard cash.

*

One day the tap stopped running. We called the surgeons. It was a long operation. Cash in brown envelopes. The usual. Who needs water?

Monday, 23 April 2012

Some hectic days ahead - a prospect on International Book Giving Day

Probably light posting the next few days as I was at the university today then straight to a reading at the Millennium Library. Tomorrow university then London, Wednesday the whole day at the Poetry Society, Thursday judging debates in Cambridge and Sunday to Tuesday in Oxford.

The Library reading was rather lovely and well attended with readings by Heidi Williamson and then, from the floor, excellent people like Tim Cockburn, Julia Webb and, well, it's late and my mind is between today and tomorrow. I read nothing from the forthcoming Bad Machine but I did read some of the brief texts, many in haiku form, that I write for the Twitter format. They seemed to go well.

Norwich has a very high population of talented poets. Whenever there is something on you're likely to hear good things.

All the prose, except one piece, is in now for Poetry Review and I think it's going to be very good.

More in bits & pieces in the following days. The Leeds saga to continue.

Sunday, 22 April 2012

Sunday Night is... Beethoven String Quartet Op 132

The Alban Berg Quartet, 2011

The whole of it! 42 minutes! One of my four favourite pieces of chamber music*, perhaps the greatest of them (though I might change my mind tomorrow). It has the depth, the drama, not too many of those grandly assertive statements, not too much of the self, just enough - because the self does, after all, exist. One depth gives way to another. It is almost unbearably moving.

*The others: Schubert Quintet in C (a fine picture of death as you'd have it), Ravel in F (sheer seduction!), Bartók (actually a tough one, maybe no.4, but certainly darkness, certainly melancholy, certainly a welcome spikiness in that witchy pizzicato).

I have never properly 'understood' big orchestral music. Maybe it's because I resist being swept along by things. Maybe one should. But my gut instinct has always been: lean into the wind, go counter.

Lean into the brass too while you're at it. And the strings! Not sure about the percussion. But yes, that particularly.

I'll come back to the subject of Leeds. Not yet finished.

Saturday, 21 April 2012

An art education: remembering Leeds (5) First year reviewed

William Scott: Painting, 1956

The first year was wonderful. At the end of it I was part of a group show at Bradford's Lane Gallery and was the most represented poet in an anthology of poetry from the art school, edited by Martin Bell, titled, well, Anthology (I have two copies in a drawer). I hadn't mentioned Martin's vital role in my own development because I was concentrating on visual art. It is not so much that I want to give an account of my own experience as such but, at this distance, it has to be told and discussed from that perspective. The very fact that Martin Bell, and, soon after, Jeff Nuttall, was there made Leeds invaluable for me.

There was no signing in in the first year. Everything was informal. You grabbed tutors as they were passing, or they looked in to see if you were in your area of the studio. You could go for weeks without seeing them. I was nearly always in the studio - early there, late to leave - so I did see them. But I was having a lucky year. Many who came on the course at the same time had no such clear sense of direction and might have been thrown by the freedom. I think it is quite likely that the majority of first year students were not there most of the time. The studio could feel quite empty. You were left to find yourself with such help as you could get.

If people didn't quite know what they wanted to do they tended to get caught up in the various performance groups. There was always something to do there and the shows could be spectacular. I remember only one other painter, though there would have been about ten. No one, as far as I was aware, was painting what one might call conventional pictures.

One of my close friends from the house began as a painter in the spirit of William Scott but within a term had moved into conceptual art. I was pumped up with colour and romantic love. Others were more detached and less giddy. A good number would be in the library checking on latest developments in the magazines; Studio International was the leader. Some were working in plastics, possibly under the guidance of Glyn Williams. But if you didn't quite know what you were after you could sink fairly quickly, to which the department's reaction might have been that teaching the students workaday crafts would only delay the process of discovering that there wasn't much substance there in the first place.

It would have been cruel if that was the case - and it actually was the case in effect if not by design - because those without that kind of substance would go away with not very much. You could have a great time if the wind was in your sails, but if there was no wind, nobody was going to blow you along.

Friday, 20 April 2012

The rooms and the metaphors

Image from here.

1. Pretty well everything in a poem works as metaphor. Even in a poem that seems to do without an overt metaphor the understanding is that we are reading it because there are metaphorical connections between what appears on the surface and other events, other perceptions, beyond the immediate, and that those are probably more important.

2. Metaphor as an overt literary device moves us, almost without us noticing, to another level of meaning. It opens the door of one room on another room and gives us another space to move in. Voila! There we are! This too is a metaphor, of course, but a reasonably comprehensive one. The sense of movement between rooms confirms our suspicion that all rooms, like all languages, are provisional, that provisionality may, in fact, be reality.

3. In a simile it is like being shown the door, having it opened, and being told: see, that room is like a version of this room, but this room remains the real one. This too is a simile. We are still in the first room. It might be important for many reasons that we remain in the first room and merely acknowledge the existence of the other one. We do after all, live here, if you call this living. If you call here: here.

4. On the other hand, no 1 follows no 3.

*

More on An art education to come.

Thursday, 19 April 2012

An art education: remembering Leeds (4) First Year

Willy Tirr, Acid Browns

The first year at Leeds was wonderful, one of the best years of my early life. For once I was left alone to develop whatever seemed interesting to me. I was a fully responsible adult human being, responsible chiefly to myself. I was also in love and hitchhiking to Norwich two weekends out of three which left only four days in the studio - but those days were so full of activity I turned out to be one of the most productive students in the place.

All the materials were free and almost unlimited since each student had a quota that could be traded off, a trade-off that could be arranged through the storeman. So I had as much hardboard, emulsion, and oil paint as I wanted. I soon decided against canvas. I didn't like the way it gave and absorbed. I didn't want colour to sink in, so it was easier to take a 4x4ft piece of hardboard, prepare it with white emulsion, then to get the oil colour on.

GS, Red Snowman, 1969, 4'x4.

Photo taken on iPhone at an angle. Painting itself fully central

I loved the colour. I loved it in tubes, coming out of tubes, sitting on a plate that served as my palette and the way it squiggled along the surface, not building up in glazes, but as fresh as it looked in the tube, as opaque and alive and itself. I would begin by painting the whole surface a strong colour then work into it, drawing slowly, crudely but tentatively across the surface. Often it would begin as a railway line, then a central motif would arise - a figure, a vase, a line of washing - to which more colour would be applied and so the whole would build not as varieties of the same colour but as one sitting on top of another like a wholly new colour, like something improvised, luminous, faintly intoxicated by itself and the general sense of well-being. Oil paint remains wet for days, of course, so the way was to work on a number of paintings at once: as one was drying the next was ready for a fresh coat.

It was naive but the tutors liked it. It must have struck them as fresh, and to be honest it struck me as fresh too. It wasn't much like any other painting - a touch Chagall perhaps. The images weren't laden with heavy meaning. They were at the edge of meaning, airy, luscious shapes that suggested other things. Vase suggested light suggested garden suggested bodies, etc. Matisse meets Chagall. Just nowhere near as good, merely possibility.

Two or three of the tutors took a particular interest in me and would come round and talk. I can't remember the conversations but they seemed to be substantial, exciting - confidential in a way, and entirely encouraging. It was flattering that artists should want to talk to me and find me worth talking to. Perhaps they found my own enthusiasm refreshing. There were, as I have said, very few painters and I was probably the most exuberant and least career minded. I was enjoying what I was doing: nothing else seemed to matter. One could make an appointment or simply try knocking on the Principal, Willy Tirr's door and he would invite one in if he wasn't busy and talk about anything that seemed interesting.

I haven't yet mentioned the other parts of course, the supposedly compulsory Art History (that I never attended because I continued painting in the studio) and the Complementary Studies that offered a choice of Film, Anthropology, Music, Sociology, Psychology and, luckily for me, Poetry. More on that in another post.

Was this an 'art education'? It seemed to me something better than that at the time: it was an understanding of what art could be. Did it help me technically? Hardly. It's quite possible my paint quality could have been better, but I wasn't concerned with 'professionalism' at that time. I had no interest in it. I just wanted to carry painting with this lovely material, and to write poems.

You might argue that this was a fool's paradise, the last kick of hippiedom, and it might have been so, but it was also extraordinarily heady and liberating. The company of artists was the key factor: their interest, their acceptance of me, their knowledge, not so much of techniques, but of art and literature and the world.

I suspect all my best paintings were done in the first year of the course. The picture on the wall of the next room was done then. It will be worth thinking about what followed.

Tuesday, 17 April 2012

Editing notes, 3

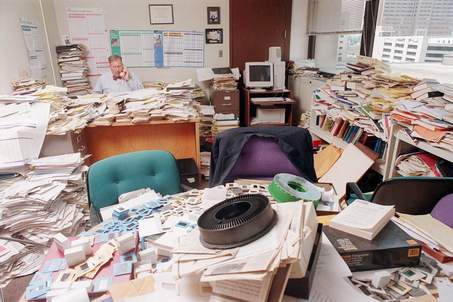

Things are at the stage that I can say a little more about the editing process at Poetry Review. Another of my avatars behind desk.

The Reviews

The three main parts of the magazine are the poems, the reviews and the centre spread. The reviews are just as you'd expect. There are the books on the shelves, a good number of them, and you try to get as many reviewed as possible. This means bunching the books and finding the right reviewer. There are, of course, those who have reviewed before and done it well. One can go to them. But it's nice to find new people, and, in some cases, the perfectly appropriate older people who might not have reviewed or even appeared there for years. There is limited space so you try to calculate how many words per page and set that as the task. If you review a lot each book gets less space but on a one-off like this I was concerned that more should be reviewed. There are, beside the new books of poetry, books of criticism and history that I have not sent for review, and new editions or translations of major figures from the past that I have. Not all. That was impossible.

The Centre Spread

The centre spread is a more open question. My idea has been to try and map territories that don't appear too often in the magazine. Fiona Sampson was a very good editor so the contents of PR were far from narrow, but no one can get everywhere, so I wanted to find poets and critics who could write about major figures, or particularly interesting figures or developments. That doesn't cover everything either but it does enlarge the map a bit. The editor also has to bear in mind that this isn't an academic magazine or the magazine of a particular range of poetry, so the task of the writer on specialist areas is to familiarise the reader with what might seem difficult if talked about one way, but is far less so when talked about differently. In effect it is a request for writers to champion that which they value and consider important - not to talk amongst themselves but to the readers of PR. If this is half as successful as I hope it will have been worth doing. If some of the poets they want to discuss have recent books out, all the better, but it's not vital.

The Poems

As to the poems themselves, there are hundreds on hundreds of them. There are also the poems the last editor left behind but did not reject or have time to reject or accept. Some will be from poets already well known, even very well known, others will have published a book or two, some less, some nothing at all. Only in the last two weeks of so have serious numbers of poems arrived addressed to me.

The editor can also ask poets to submit poems. These can be from poets he or she particularly admires or those who might not have appeared in the magazine before but in whom the editor believes. One guiding principle for me and I would guess other editors - it is not a rule, it is not written in stone - is that if someone has appeared in a very recent issue they should give place to those who have not appeared in the period. I would like to think that if Eliot had offered us Prufrock one quarter and The Waste Land the next I would not have turned either down, but might have considered holding back the second for an issue or two unless I felt the whole think was so hot it absolutely had to appear. A delay can help a poem create an audience. Waiting can be good.It can make things even hotter. The difference, of course, is that I am editor for only one issue and cannot hold things over. I can merely make a folder, hand it over to my successor and suggest that it might be good to look at some.

One tries to choose the best, that goes without saying, but there is a lot that is good and many that are more than good enough. If an editor has invited poems, there is an obligation to use at least some of them. Then there are the poems submitted independently by those the editor knows in one way or another. Some may even be acquaintances, which in the world of poetry, is almost unavoidable. Friendship is not, and cannot be, an issue. The related question of who the editor considers good or underrated is more difficult. Editors will know some work better.

One more factor in choosing. There isn't a theme at the beginning, but a theme, or themes, may arise, so that of two poems of roughly equal virtue one may become more attractive because it fits so well. I have always believed that there is a kind of story or trail in books and magazines, a natural sequence of reading. That may be a personal quirk but I feel entitled to it. One has to choose on some principle and when dealing with many hundred there isn't time to weigh small differences in merit. So some very good poems are there instead of other very good poems because they seemed to me dead right where they are.

The best are easy, you just have to spot them. And I have spotted a very good number of excellent poems some by people whose names I know, some, to my great joy, by those I have never heard of, or only distantly. The great joys are an outstanding new poem by an outstanding writer, the chance to print someone who has not had their due despite outstanding work, and discovering outstanding work by the unknown. I think I have done all those three things.

*

There are some other issues on which I'll post in due course, but I thought it worth explaining what seems like a mysterious process. It is tough work, tougher than editing a book. It is long and tiring. I have occasionally tried to tell sceptics that the greatest pleasure for any editor is in discovering the new. That much should be obvious - there's no great credit in taking what is already known to be good. One wants the known good, very much so, precisely because you know it is good. It would be a coup to have a new poem by MacNeice, say, but to find a new MacNeice is, in some ways, better still.

Next time back to the art school. It has been a very long day and I write this at the end of it.

Monday, 16 April 2012

An art education: remembering Leeds (3) Interview & arrival

Harrow School of Art, 1969, by kind permission of Richard Plank, who is on the extreme left, back to the wall. I am not there, having left the previous year but knowing a number of people in the photo.

Interviews for Leeds were legendary and rather terrifying. The rumour was that they hardly looked at your portfolio. They were interested in you as a person. There was a story about one candidate being asked to criticise the portfolio of another. There was one about a candidate who said he enjoyed climbing and who was then asked to climb around the interview room without touching the ground. I suffered no great trial but when I was asked who my favourite artist was and I answered Cézanne, one of the interviewers cried out that he hated Cézanne. Whatever I did in response must have impressed them - I probably said something like, 'Well, you can't please everyone' - because they let me in.

The college had only just moved from the old Jacob Kramer to be part of the new Polytechnic. The building was exposed and windswept. An ex-school student of mine was to be swept off the stairs in one great gust of wind a few years later and blown to the ground where she was knocked senseless.

I had digs for the first year, out in Halton, near Templenewsam, sharing the house with some twenty or more others. It was in fact two neighbouring houses knocked together with fields at the back. The other students were mostly male but there were some four girls too. I was in a double room at first with a graphic artist called Derek who badly missed his home in Crawley. There was a snooker room in the cellar and a small bar. The landlord, Roger, an ex-teddy boy, liked me because I played the piano (there was an old upright there) and because I was polite. To everyone's amusement I went round shaking people's hands when we first met.

The poly was a good bus ride away. In the first week we were shown the studio, told to find a space and make it ours, then were instructed to go to Woolworths, to buy a small tin globe of the earth, and to do something interesting but unspecified with it. Having thought a couple of days I decided to give it away, but, just to show it was not abdication of responsibility, I cut a hole in the side of the globe and slipped a £1 note inside it. I offered it to a woman pushing a pram and she accepted it. I should say that £1 was worth rather more than it seems now, the rent for our handsome Victorian flat two years later being £2.75 a week.

When I reported what I had done, the tutor in charge, Robin Page congratulated me and was very surprised when I got some canvas and started painting.

Why are you painting? he asked me.

I told him I wanted to be a painter.

No, no, he argued. We're not interested in painters. What we want are beautiful people.

I had been a beautiful person giving away the globe, now I was just a painter. I don't think we spoke again.

It was interesting. Putting aside the sixties cliché about beautiful people, the argument seemed to be that action need not involve engagement with traditional materials, it needn't even involve the making of sculpture. It was not about making but being, and that sense of being had a kind of magical moral dimension. It was romantic conceptualism without the name: more magic than theory, and more circus than studio.

Where was my Harrow grounding in techniques? What was it worth in the court of magical acts, in a world of carnival and gesture?

It was the one and only project we were asked to undertake in the whole of the three years.

GS on the mound of earth at the back of Leeds Polytechnic (College of Art), 1969

Sunday, 15 April 2012

Sunday Night is... Duke Ellington 'It Don't Mean a Thing' 1943

From YouTube notes: Ivie Anderson sang the vocal and trombonist Joe Nanton and alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges played the instrumental solos. The title was based on the oft stated credo of Ellington's former trumpeter Bubber Miley, who was dying of tuberculosis. The song became famous, Ellington wrote, "as the expression of a sentiment which prevailed among jazz musicians at the time." Probably the first song to use the phrase "swing" in the title, it introduced the term into everyday language and presaged the Swing Era by three years. The Ellington band played the song continuously over the years and recorded it numerous times, most often with trumpeter Ray Nance as vocalist.

I love early Ellington for probably much the same reasons Larkin did: the joy of it. Which is not to say it is an untroubled joy, as the note above makes clear. I think that was always understood: that was what made the joy so good.

Art needn't spring from suffering. Consider Lartigue:

LARTIGUE: Cousin Bichonnade in flight, 1905,

Here is an old poem from a series based on Diane Arbus, who might seem to be the proof contrary. Characters such as The Mystic Barber, the Emperor of Byzantium and the rest were characters met by Arbus, who would ask people in the street 'Can I come home with you?' if they seemed interesting enough. Often they said, 'Yes'.

Bichonnade

...that we may wonder all over again what is veritable and inevitable and possible and what it is to become whoever we may be - Diane Arbus

The Mystic Barber teleports himself to Mars. Another carries

a noose and a rose wherever he goes. A third collects string

for twenty years. A fourth is a disinherited king,

the Emperor of Byzantium. A fifth ferries

the soul of the dead across the Acheron. There's a certain abandon

in asking, Can I come home with you?

like a girl who is well brought up, as she was, in a fashion,

who seems to trust everyone and is just a little crazy,

just enough to be charming, who walks between fantasy

and betrayal and makes of this a kind of profession.

It takes courage to destroy the ledge you stand on,

to sit on the branch you saw through

or to fly down the stairs like Lartigue's Bichonnade

while the balustrade marches sturdily upward, and laughter

bubbles through the mouth like air through water,

and the light whistles by, unstoppable, hard

and joyful, though there is nothing to land on

but the flying itself, the flying perfect and new.

Cunning rhyme scheme on last two lines of each verse. Trying to fly down the stairs. Poem from Blind Field (1994)

Saturday, 14 April 2012

An Art education: remembering Leeds (2): Foundation Course

That's a 1939 life modelling class above. There are a number of photos of some of the 1969 Harrow School of Art class here. We had just gone but I recognise some faces. Phil Hicks is the tutor here.

The foundation course at Harrow did what it said it would do: it laid a foundation. But for what, and how?

The art school was in the main street but the foundation school was in an old primary school down another. I can see the staff quite clearly now: the principal, Ivor Fox; the drawing teacher, Sam Marshall; the sculptor and fibreglass specialist, Phil Hicks; the sculptor, Dave Petersen; the painters,Ken Howard, Roy Rodgers and Wendy Smith - but after that the names fade a little though the faces remain. The screen-print studio was a woman with glasses who spoke as though we were primary school children and who got us to make cut-out screen masks; the lithography studio was known as the Bot Cave on account of the dour tutor, Botting; the etching studio was led by the fiery Hilary; art history was taught by Demery and Paul Overy.

In the first term we did everything, in the second, having made our application to the diploma courses towards which a Foundation certificate was the first necessary step, we concentrated on either fine art or some form of design. Some of us become textile designers, some worked in fashion, others went on to jewellery. Some stayed on a second year.

I imagine other foundation courses were similar in terms of broad preparation.

I suspect we were rather well taught for the most part. Personally, I was half-way proficient in some of the disciplines and rather less so in others. I was making sculpture with canvas soaked in resin, I had carved some wood. My painting took on a post-cubist look following my experience of Cézanne. It wasn't much good, any of it, not what I really wanted to do, but I enjoyed it all the same. I was still horribly ignorant. It was, I knew, an interlude before life proper could begin and I had, after all, learned something. It was an honest run through of skills that had been appropriate to working visual artists for years: the beginnings of craft.

None of it, however, prepared me for the next stage at Leeds. Nothing was immediately useful. It was like being prepared for something that no longer existed. The division between art and craft was the point.

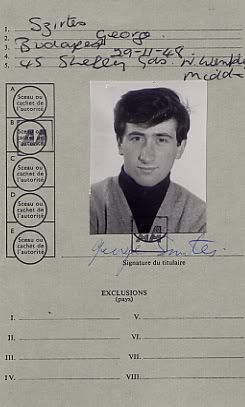

GS at about 18, just before art school.

Friday, 13 April 2012

An art education: remembering Leeds (1)

I took up art in my third year sixth, having failed to get into medical school and needing to retake Physics A Level (I did and climbed one grade from E to D pass). I was in the sixth form with contemporaries gone and too much time on my hands. I had started to write poetry but had given up art in the third year, being told I was too messy. I probably was.

Go up to the art room and do something useful, they said, so I did. The art room overlooked the netball court so there was always the prospect of watching the girls play netball if all else failed. But it didn't fail. My timetable didn't fit normal A level so I was up there on my own or with some younger classes. Sheila Mayer (Miss Mayer to me then), the art teacher, gave me the materials and would sometimes come to talk to me and showed me books full of paintings - Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne - which, as the cliché has it opened a new world to me, since we had nothing like that at home and such artists, if their work was known at all, were never mentioned. Better still, I found I could draw and paint and get a likeness. I had found a skill I didn't know I had, and had in fact been told I didn't have. My still lives, even when painted straight on, actually looked like the objects they were supposed to be depicting.

But it wasn't depiction that grabbed me, it was the freedom to create any world I chose with no more than a sheet of sugar paper and some powder paints. It was like a new power. I did it only for three months but finished up in the exam with an A that was easily my best grade, and the best that year. My composition paper, as it was called then, was a scene of Stephen Dedalus teaching a class (I had just read Ulysses, or part of it, for the first time, and had seen the film.) There was some other funny stuff going on in the picture but I can't remember it.

Over the summer of that year, in 1968, my family paid its first visit back to Budapest since leaving it in 1956. A lot of fascinating things happened while we were there, including the invasion of Czechoslovakia, but I also have a very clear memory of looking at a Cézanne still life in the Fine Art Museum, my eyes filling with tears for a reason I couldn't explain, except that it was something to do with something being very right about the picture. I believed in the world it showed and the way it showed it. However, because of the invasion our planned three-week stay was cut in half.

On return I found I had been offered a place to read Psychology at Brunel, but decided, at the last minute, to apply to Harrow School of Art as well. I took along my portfolio in September and was given a place immediately. Against all parental caution I took the offer and gave up Brunel. My life had changed enormously and very quickly. It was the beginning of better things. The process of becoming an adult, that had started with the understanding (an entirely private unspoken understanding) that I would be a poet, was completed on arrival at art school. As a child I was a gifted question mark, a projection of my well-intentioned parents' dreams. As a young immigrant schoolboy I had disappeared into a fog that hung around me for at least six years at the end of which I was supposed to enter medical school and become a caring genius in a white coat. As an adult I was to be a poet and an artist. That being settled it only remained to see what that adulthood would be like.

What would I learn art school was the first question? This isn't setting out to be a memoir, more notes on a way of thinking about what art and art education meant. I'll write a little more about that in the future.

ps Of course our art room wasn't as in the old photograph above. I bet they didn't have the chance to look down and watch girls playing netball.

Thursday, 12 April 2012

In London. Travelling with ghosts.

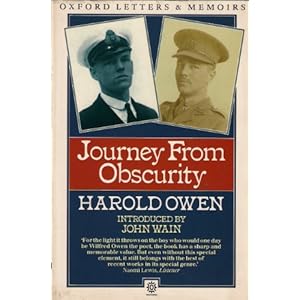

Watching the steely sky gentle into a hint of sun I am reading M R James's The Mezzotint and get into a Twitter conversation with writer Robert Hanks and the Rev Richard Coles about James and ghosts. At some point I mention two incidents from Harold Owen's three-volume memoirs of his family and his brother Wilfred, Journey from Obscurity. In one of them Harold meets Wilfred on the day of Wilfred's death, in the other, the one I was trying to remember, there is an incident in a wood, with the whole family involved.

At that point we reached Cambridge and on the platform I bumped into a university colleague and we talked all the way to Kings Cross, so the thread was lost. The rest of the day was very full and it is only now, having returned home, that I have found the incident. It is in Volume 1. Childhood, pp79-83 in my edition. It took about quarter of an hour to find it. Harold Owen is not a great writer of prose, slightly awkward, but had a wonderful eye and an extraordinary memory and sensitivity to place and mood.

I won't try to summarise in full here. THis is the Twitter log as addressed to Robert and Richard:

The Owens are in Ireland, father chooses unfamiliar way through dense woods. Something 'large & animal like moving ... along a branch. They all see it. Wilfred trembling. Suddenly heavy rain then stops. Mother 'desperate' to..get out of wood. They are surrounded by cloudburst vapour. They walk between trees down seemingly endless tunnel...and suddenly come to clearing with 'what appeared to be a sheet of water'. High wall of mist cuts across in...perfect straight line, some menacing sense of danger. Father says it's all nonsense & walks ahead, they follow...noticing mist & water receding at precisely the pace they're walking. All trembling now. Father moves...ahead, water & mist retreat before him. Mother turns & screams. 10 yards behind shadowy figure of a tall..man, radiating same 'cold incandescent quality' as the lake. All feel 'desperately insecure'. Father...addresses the man. Man contorts 'into a frenzy of fury' raising his stick. Father speaks again to same...effect, another paroxysm. Father angry walks towards man who retreats keeping precisely same distance as if...the pair were synchronized. When father retreats figure comes forward etc. Father advances fiercely. Figure disappears...Mother cries, 'Tom, Tom, come back'. Father stands motionless, returns depressed. Lake has disappeared...

That's it, but the story is told at a very good, compulsive pace, which is probably why I remembered it relatively clearly.

Wednesday, 11 April 2012

Some Attila Jozsef fragments on his birthday

Precisely 107 years ago, Attila József, one of the greatest twentieth century poets was born in a Budapest slum. Son of a poor factory worker and a peasant woman, his father deserted the family when he was three. He was fostered out for a while but came back. A relative put him through school but he failed to get into university because one of his poems was taken to be offensive. His first book of poems appeared when he was twenty-two and he survived as best he could by his writing. He joined the Communist Party then left it and died, run over by a train at the age of thirty-two. There are a number of good translations of him the best probably being Edwin Morgan, but there are others including the one by Frederick Turner and Zsuzsanna Ozsváth. Other interesting ones include those by Peter Zollman, John Bátki, and Peter Hargitai.

I have translated only a little of József. That tone is hard to strike as well as keeping form. It is colloquial, romantic yet firmly rooted in realism. Here are a few I prepared earlier. The first four lines form the last of three quatrains from Reménytelenül (Without Hope). It can serve as epigraph.

...My heart is perched on nothing’s branch,

a small, dumb, shivering event:

the gentle stars jostle and bunch

and gaze on in astonishment.

Fat Drops of Rain...

Hizlalt esö

Fat drops of rain on the roof,

metallic pit-a-pat.

Cluck on old hen, brood me time,

hatch me some of that.

Produce the eggs, sweet mamma,

that any mother lays,

delicious soft blue, green,

and scarlet days.

I’ll wait for you. I’ve got no cash.

There’s nothing I can buy.

My heartbeat shakes me as I feel

your fluffy feathers fly.

It beats and shakes. I hear it,

gloomy, proud, aloof.

The thoughts of a tramp beneath

a first class carriage roof.

The silent machine

A hallgatag gép

Look, the silent machine has arrived

and rolls on across hulks that are still squealing.

The medium groans. Now, through the masses

come ranks of workers wheeling.

It’s hard work. How can they squeeze through

when white-eyed gods in an advanced state

of decomposition, stand either side, to watch

bankers flit in and out at the gate?

The hoops of the world are cracking.

*

We’ll found a workers’ state of refined steel -

on a bed of polished rock

and see its symbol flitter across lined faces

like a snatch of song through a tenement block.

*

May the butcher’s hefty cleaver

Dagadt hentes bárdja

May the hefty butcher’s cleaver slice you open

so the snow falls down the gaping wound in your back,

tyrant of trembling hands and witless cack.

The three fragments were translated for Thomas Kabdebós Poems and Fragments of Attila József

Tuesday, 10 April 2012

The broken mirrors: Rita Hayworth, Don Martin and I

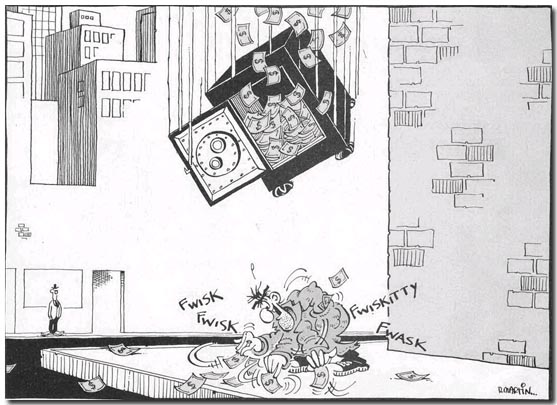

There was an old Don Martin Cartoon in the Mad magazine of my youth, where a character spots a hair sticking out of the top of his arm. He gives it a tug and the arm falls off.

So it is with many things. You move one small thing and the horrors leap out. Today I had to find a document on my computer. I have a back up drive, I use Dropbox and, out of fear of losing everything - as I did once - I have back-ups on the computer. And of course I had copied everything across from the old MacBook to the new, lovely and light MacBook Air.

I noticed at the time that I had very little space left and tried throwing out a few old applications without it making much difference. But now, in looking for the missing document, I suddenly saw that the problem was not in the applications but in the apparently harmless documents and photographs.

They were everywhere.

It was like finding myself in a booth full of mirrors, somewhat like Rita Hayworth in The Lady from Shanghai. As below.

Everything was coming at me in quadruple or quintuple or worse. Had they all been simply copies of each other it would have been easy, if a little fraught, to throw the copies away. But they were not the same. They had been modified in different places at different times. The hall of mirrors was cracked. I had to move carefully not to throw away something valuable.

And the valuable things appeared looking a little lost and bewildered. I had to nurse them to a safe place where those that belonged together had the reassurance of each others' company. Whether they were really valuable or simply objects of curiosity I had no time to tell. They just looked happier in their folders.

But the mess, the thorough awful soaking bollocking mess of it was a little frightening. After a while it isn't the mirrors you worry about but the figure they show, the mind that is the source of the mess, the man who put the mirrors there in the first place then cracked them and splintered them.

And that's a whole day's work and it still isn't finished, just a little tidier. Once the single mirror is restored I should be able see what shape it makes and what it shows. One doesn't want to be looking into mirrors very much. One mirror is enough in any case. We are not Rita Hayworth, nor were meant to be.

Monday, 9 April 2012

Abby Innes on Hungary: Viktor Orbán goes for broke (3)

The third part of Dr Abby Innes's blog, cross posted from the LSE with her permission.

In his speech to large crowds attending national day celebrations last week Orban vilified the EU as no better than Hungary’s old Soviet oppressor: ‘We will not be a colony’ he declared and not for the first time he drew direct analogies between Moscow and Brussels, rejecting the ‘unsolicited comradely assistance’ of the EU – a fabulously disingenuous reference to the Union’s attempts to get Hungary to honour its voluntary commitments. The EU’s finance ministers have duly resolved to withhold half a billion Euros in cohesion funding. All of which leaves the regime with increasingly polarised choices. Though playing for time in EU/IMF negotiations, in public Orban continues to spoil for a rhetorical fight as one of the few remaining proofs of government virility. As such he is dragging Hungary into a diplomatic game of chicken, and so long as Orban doesn’t blink he offers himself as the hero of a projected national martyrdom. As such he is offering the fellowship of misfortune to that sizeable population that feels marginalised by the rapid liberalisation of the economy; that is overcome with anxiety about the future and resentful of the entanglement of figures, information and exhortations to ‘discipline’ coming from the wealthier countries to the west. If Orban backtracks now he is ‘selling Hungary out’, but as things stand, with his persecution manias, his resurrection of communism’s ‘combat tasks’ in nationalist form, with his purging of the non-faithful from the public sector, the judiciary, the media, culture and education, allusions to Greater Hungary and promises of ‘economic autonomy’, Orban is selling his people a catastrophic lie. The lie is that Hungary can flourish as a paranoid, racist, xenophobic one-party state with a patronage-based economy: with a reversion to those calls for self-determination that require enemies abroad and racial inferiors at home. Orban’s ministers are too afraid to calm the hubris which is increasing evident in Orban’s actions and this can only end badly: the political economic contradictions will mount and ordinary Hungarians are already paying the price with a deepening of the stresses that brought Orban to power in the first place. For a democracy scarcely twenty years old this is a tragedy which should give all Europeans pause. In particular the EU’s economists need to think hard on the politics of austerity, because Hungary is not the only member state with an illiberal tradition on which its more ambitious politicians may call, when cornered. [Ends]

*

Some key phrases:

'...the most almighty recasting of the rules of the Hungarian political game: what has ensued is a bacchanalia of populist-nationalist elite self-indulgence and hatred-mongering that has taken Hungary’s international reputation from a regional reform leader to pariah status in two years, and its political economy deeper into the mire...'

'...Orban’s solution was to insist that the emerging market dilemmas that are structural to a population with European expectations of social cohesion are solely the product of ‘communist’ corruption and networking. This accusation duly proved more electorally successful than promises of further belt-tightening...'

'...Orban is selling his people a catastrophic lie. The lie is that Hungary can flourish as a paranoid, racist, xenophobic one-party state with a patronage-based economy: with a reversion to those calls for self-determination that require enemies abroad and racial inferiors at home...'

*

In the meantime Jobbik has reverted to the old anti-semitic blood-libel. If Fidesz wants to retain any shred of respectability it has to put a pretty decisive stretch of clear blue water between itself and what sometimes seems like its pet pitbull opposition, Jobbik, as does the right wing Fidesz-supporting Hungarian press, of course.

Abby Innes on Hungary: Viktor Orbán goes for broke (2)

Dr Abby Innes of the LSE, continuing & the cross post from the LSE's own blog. With grateful thanks.

How did it come to this? Coming out of the gradually reforming system of ‘goulash communism’ Hungarian governments tried the longest of the EU10’s frontrunners to hedge the region’s emerging market pressures after 1989, and so administrations of all stripes (including Fidesz) ran competitive (i.e. low) personal income and corporate tax rates to attract FDI while trying to maintain spending on welfare and skills formation. The result was relatively low inequality for this region but an increasingly crippling tax burden on employers, inducing what Esping Andersen has elsewhere dubbed the ‘death spiral’ scenario of low employment and lowered tax contributions requiring high payroll contributions to support the remaining welfare system, which further lowers employment, stunting growth, increasing pressures on welfare... Even after entitlements were reduced the spiralling costs of cash transfers in Hungary increasingly crowded out resources the economy needed to retain its competitive edge, as their low wage advantage ebbed away and the relatively portable FDI which Hungary primarily attracted moved eastward. This developmental bind duly put the country’s main free marketers, the born-again Blairite (reform communist) Hungarian Socialist Party into a near impossible electoral position: hence the fiscal make-believe of 2006. (In fact the leaked 2006 speech of the Socialist Prime Minister, Ferenc Gyurcsany is most striking for its honesty regarding the brutal character of Hungary’s realistic economic choices – along with prodigious levels of swearing.) Orban’s solution was to insist that the emerging market dilemmas that are structural to a population with European expectations of social cohesion are solely the product of ‘communist’ corruption and networking. This accusation duly proved more electorally successful than promises of further belt-tightening in a country that had already endured the complete opening of the economy to foreign investors, steeply rising welfare and employment insecurity for twenty years and steadily rising unemployment for the most recent ten. But the belt-tightening has come anyway – as, short of a simultaneous reconfiguration of global capitalism - it had to.

In government Fidesz adopted an incoherent ‘growth’ strategy that liberalised on the one hand, slashing employment and unemployment protections, for example, even as it politicised the Central Bank, the State Audit Office and the Fiscal Council, and by now their programme is reduced to chaotic acts of fire-fighting. Orban favoured those on a higher income with a flat-rate personal income tax of 16% in 2011 even as welfare cuts flattened demand among those on lower incomes (with a higher propensity to consume) but his government reacted to the subsequent decline in tax revenues with an increase in the employer social security contributions they had pledged to cut, a raise in VAT to a massive 27% and a hike in the minimum wage by 19%, none of which will improve demand or increase employment. These measures come in the context of an increasing inability to raise finance either from financial markets or from the IMF or the EU, with which the government is at loggerheads, even as Hungary teeters on the brink of a sovereign debt default.

[concluded in next post]

Abby Innes on Hungary: Viktor Orbán goes for broke (1)

This piece by Dr Abby Innes, Lecturer in the Political Economy of Central and Eastern Europe, European Institute, LSE is cross-posted from the original source at EUROPP blog LSE. I am grateful to the author and to LSE itself for letting me cross post. It is good for my untrained eye to see the matter from this point of view. For convenience of reading I will post it in three parts, all three today. Comments at the end of the third part.

Contemporary Hungary is offering an abject lesson in how quickly democracy can go to hell when politicians confront thankless options and take the low road. The Fidesz-dominated coalition government came to power in 2010 on the high stakes promise of ‘no more austerity’ and it has been selling a fantasy of national renewal on the top of increasingly authoritarian government practice and deteriorating financial conditions ever since. To make good on its electoral promises one of Fidesz’s first measures was to pay for tax cuts by expropriating private pension funds back into the public budget: an act that put the budget into a one-off surplus for 2011 but which damaged Hungary’s international financial credibility which worsened thereafter – government debt has had ‘junk bond’ status for many months now. By March 2011 the government announced its economic strategy in the form of the Széll Kálmán Plan: a programme, so it turned out, of severe austerity, particularly for lower income groups. It presaged significant cuts in health, welfare entitlements and higher education but promised the creation of a million jobs within ten years.

At the root of Hungary’s sluggish growth and extreme political remedies is the lowest employment rate in the region – barely one in two of those of working age - and an exceptionally high tax wedge on labour, second only to Belgium’s within the OECD in recent years. By 2006 Hungary had Swedish/French levels of public spending at Polish levels of per capita income. When coupled with a post-2007 crisis in privately held foreign debt the former Socialist government was left with nowhere to go but to unprecedented economic retrenchment: something they were no longer trusted to manage after revelations they had already lied about the real condition of Hungary’s public finances back in 2006 in order to win that election, and subsequent corruption scandals. Enter Fidesz and Viktor Orban in a coalition with the Hungarian Christian Democrats, with a constitutional supermajority and the temptation, given the unrewarding economic situation, to embark on the most almighty recasting of the rules of the Hungarian political game: what has ensued is a bacchanalia of populist-nationalist elite self-indulgence and hatred-mongering that has taken Hungary’s international reputation from a regional reform leader to pariah status in two years, and its political economy deeper into the mire.

[continued in next post]

Saturday, 7 April 2012

Being photographed: good me, bad me

One has two selves: the one in the good photograph and the one in the bad photograph. What does the good photograph mean?

I sometimes think we are engaged in a competition with reality, or rather, that there are various realities that are presented to us and that we tend to choose one over another. We do this by taking over the presenting, less by addition than by subtraction, by removing the bad ones in an act of censorship. So we pile up the good photos, thinking that somehow the aggregate of these photographs, their cumulative effect, might in some sense be us; that we might be able to introduce our desired aggregate reality, like the thin end of the wedge, into the space between rapidly passing moments that are, surely, no more than mere impressions that must fade in time, so that, eventually, the photographs take over and become us in memory, in our and others' memory, supplanting the hapless, plain, un-photogenic creature that crawls, stumbles and trips about our booby-trapped everyday existence.

And we believe we have a certain right, or at least a claim we can lodge in the furtherance of that right, to retain the copyright on ourselves and our images of ourselves in the same way as we retain the copyright to our productions; that, in effect, we have the right to produce ourselves as we would wish to be produced.

This copyright image, we feel, belongs to eternity in whatever sense we understand eternity. That it is the Platonic model of our ideal, and therefore properly real selves. This, amigo, is my nose as I would have it be and it is no business of yours how it should be. Listen buddy, this chin and neck are mine not just in the long run, but in the run to end all runs, in the precise standstill that constitutes the self beyond this incidental moment into which it just appears to be concentrated. This will run and run. Believe me.

Friday, 6 April 2012

Airs for William Diaper

I have been tweeting from William Diaper's gorgeous version of Oppian's Halieutics. So it seems appropriate to put up this poem that appears in the New and Collected Poems (2008), and peculiarly appropriate in the association of Good Friday with fish, fish having been Diaper's special subject.

Airs for William Diaper

Here is a young fellow has writ some Sea Eclogues, poems of Mermen, resembling pastorals of shepherds, and they are very pretty, and the thought is new. Mermen are he-mermaids; Tritons, natives of the sea. Do you understand me? I think to recommend him to our Society to-morrow. His name is Diaper.

– Jonathan Swift, Journal to Stella

1.

My child, listen. When you and I arrived

fresh from our mothers’ wombs we floundered

in red air and bawled our guts out, shocked

by everything: the fearsome slap of hands

we could not see, the barbarity of cold

we needed wrapping against; the light that pressed

hard fingers against our firmly shut eyes

though we did not know it. Air was dangerous,

the terrible air we needed for survival

yet needed first to survive. And you and I

we were together in this as was the one

who nurtured you in darkness, eely, frothed

and struggling like Blake’s babe ready to sulk,

the alien familiar as we are still, my child,

you with your closed heart and I with mine.

2.

He came to visit Swift who said: “It is a poor

little short wretch but will do best in a gown,”

though later he called at Diaper’s door

and found him “in a nasty garret, very sick”

in an admittedly poor part of town,

so gave him “twenty guineas from Lord Bolingbroke”

for his considerable gifts and knowledge,

as appropriate for a fellow of Balliol College.

3.

A deep-sea fishiness is half of sex,

all wriggle, squirm, thrust, muscle, ooze and flex,

plus otherness and drowning as if this

were necessary to perfect our bliss.

Now fish, now slime, spermatozoa swim

from rampant pecker into depths of quim,

and so our eelets swell and drowse in heat

their limbs more fin than human hands or feet.

Too long in genial beds, we rise for air

as fish might rise for bait that soon must tear

the delicate mouth. Then watery substance parts:

light shoots barbed arrows through our fishy hearts.

4.

To silver poets scaled in silver, gaining

the silver medal of the moon

like a delicate staining,

the small fry

who die

unremarked and soon,

whose skin is pale and silvery as a pond,

whose hair is frond,

who dance

according to the slim chance

of names like Diaper, Edward Chicken, Stephen Duck

with a year or two of luck,

then greeted by no Gotterdammerung,

but by the greater silver

of John Crowe Ransom, Norman Cameron.

5.

Wrote couplets enough to furnish a whole choir

of scales and fins. His objects of desire

were human beings coupling, pair by pair,

each doubled vision swimming through the air.

now twisting, now cording like rope:

warmest flesh, the perishable face

packed with hope.

6.

My child I sometimes despair of the loss

of that which is not clear to the naked eye.

When I myself was a child the table rose

like a giant, its sharp edges sky-high.

I did not know sky from ceiling, my mother

from God. The words would open and close

their fishy gills by my microscopic ear

until I learned to distinguish one from the other.

And so I watched the wordlings shuffling across

the deep spaces of my attention like specks

cavorting within the dimensions of their sex,

smaller than I was but more sweet and clear.

Thursday, 5 April 2012

The clerihew: a self-righting doll

There are times when there is nothing heavier than light verse. The Victorians groaned under the weight of it. Thomas Hood could be marvellous but, just as often, laboured, a kind of melancholy proto-Charles Pooter with a rhyming dictionary and an obligation to tell jokes. Lightness is not the same as light verse.

There is, though, a realm I enjoy that is very much like play, particularly at moments of tension, when a flood of nonsense breaks down some wall and the sheer joy of invention takes over.

For a while now I have taken occasional recourse to the Clerihew, the form coined by Edmund Clerihew Bentley, aka E C Bentley, author of the Trent series of detective novels, but also practiced with great skill by Chesterton and Auden. Here is a set I wrote in an intense half hour or so this evening in a state between tension (about things to be done) and sleepiness (at the thought of them). They were a great pleasure to write, each about an artist

Rene Magritte / liked his rum neat / and would never think of adding Cola. / He'd sooner eat his bowler.

*

Pierre-August Renoir / simply adored Film Noir / and kept nagging at Jean / 'Make your old dad a Film Noir! Aw, go on!'

*

Claude Monet / Resisted all forms of donné. / When someone suggested he should paint the cathedral at Rheims, / he replied, 'In your dreams!'

*

Georges Braque / decided to pickle a shark / as a kind of tableau, / but then left it to Pablo.

*

Michelangelo Buonarotti / woke up feeling grotty / having painted an enormous fresco / for Tesco.

*

Fra Filippo Lippi / was kinda dippy / but succeeded in laying tons / of nuns.

*

William Blake / worshipped Veronica Lake / but secretly thought The Blue Dahlia / something of a failure.

*

Dante Gabriel Rosetti / was never mean or petty, / though he would occasionally fiddle / with Lizzie Siddall.

*

Jacques-Louis David / refused to read / Karl Marx. / 'Too many sharks'.

*

J M W Turner / liked a nice little earner / and was untroubled by greed, / painting Rain, Steam AND Speed.

*

Jack B Yeats / told all his mates / to ignore his brother Willie. / 'Those bloody fairies are just too fecking silly.'

*

Antonio Canaletto / could sing falsetto / but once he was off his face / he growled in bass.

The Clerihew is a brief biography in verse. Its rules are both simple and complex. The simple rules are that the first line should be a proper name, that there should be four lines in all, and that the first line should rhyme with the second and the third with the fourth.

The complex part is to do with timing, the requirement being that the lines should be of irregular length, as long or as short as sounds best for bathos. Bathos is, I suppose at the heart of it, but the route to bathos is itself complex. There isn't a single route like a magic formula of course, but it's possible to say something about it in general.

Given that the first line is the name of the subject, the second is there to suggest that the biography is unlikely to be true. Sometimes it refers to an invented character trait, sometimes to an invented minor incident. The first two lines together then form a kind of statement likely to open the door to the ludicrous. Once having lurched into the ludicrous the third and fourth lines might well follow a logic proceeding from the second line, or instead, return to something the reader might well consider genuine in some way.

The clerihew is not a form of satire. The very form of it suggests otherwise. Satire springs from a position of rightness and has behind it the notion of something stern with which to chastise the object. 'Satire or sense, alas! can Sporus feel / Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel' writes Pope in strict heroic metre and perfect rhyme.

The structure of the clerihew is a ramble, a lurch, an avoided pratfall: its lightness consists of a seeming inadvertency. It has no attitude. It is like one of those self-righting dolls that represent a character that is never heroic, a passive victim you can tip over with your finger, but who then swings back and rights itself. It has neither arms nor legs for balance. It is a form of helplessness. Svejk is the perfect psychological example. He is ludicrous yet survives.

You can't write a clerihew by following complex guidelines of course. The lines have to feel, and actually be, improvised. They right themselves by something within, a kind of comic grace.

And that is a relief. Comedy isn't a serious business because one labours over it: it is serious because we need it, sometimes quite urgently, the laughter bubbling from lips that might well have been clenched.

Wednesday, 4 April 2012

John Davies at the SCVA, with friends

John Davies, Bucket man, 1974, Mixed media

Dear friends over from Hungary. We pick them up at the station in heavy rain and drive to the Sainsbury Centre where we mooch and marvel among the permanent collection which is arranged primarily geographically and anthropologically but with sprinklings of Francis Bacon and John Davies, as well as Degas, Modigliani, Soutine and Picasso. Much of it was bought in the 70s and is beautifully laid out.

Davies is interesting because while he is quite well known as a sculptor he is nowhere near as public a figure as Francis Bacon was. Sir Robert Sainsbury (1906-2000) must have picked up his work before Davies even in his thirties, and his work lives most intensely here in the early Norman Foster building.

One looks, and thinks George Segal, then Ana Maria Pacheco, or a Pop Artist like Marisol or even Duane Hanson, but Davies's figures are, on the whole, more abstracted, more lost in their sense of the transformative moment, than Segal's monumental ordinary folk, than Pacheco's doomed, wicked, or enchanted totems, and, unlike Marisol or Duane Hanson, they make no comment on popular life. There is usually an item or two of mysterious significance included with the naturalistic yet oddly frozen figure - a mask or a board, just enough to be unsettling without becoming stagy-sinister. The faces are intelligent but withdrawn behind a veil of something like suffering,

Whatever the Sainsbury family saw in them they certainly thought them important enough to collect and display permanently in numbers.

The Bacons are a mixed bunch, not all fully resolved but still haunting. Afterwards back home to talk and continuing the talk in the nearby Number Twenty-Four which does a very good celebratory meal. We are celebrating the visit.

Tomorrow the weather will be better, That's a promise.

Tuesday, 3 April 2012

Call the roller of big cigars

Another long London day in the course of which I meet a curious Greek and a poetryfilm-making Scot. The Greek woman's name was Sylvia, but none of the available swains commended her, the Scottish filmmaker is Alastair Cook who makes films that are poems. They look rather abstract and beautiful and the idea is that we might do something together. That sounds inviting.

Both were met in the Poetry Cafe, albeit Sylvia was chance and Alastair was arrangement. The arrangement was possible because I was working at Poetry Review where it sometimes seems as though I have done the first tranche of hard work and at other times it seems I haven't. I sit at the end of the long table sorting through envelopes and entering figures. What has to be in the magazine beside what I have put in it? How much space there really is. Typeface and size. Images. Forms of letter. Lists of who is doing what. Who was doing what.

In some ways it is tempting to do more of this magazine editing stuff, in other ways it is quite impossible, at least for me, at least for this magazine. Just impossible for any perhaps. Meanwhile a new translation contract arrives and ought to be signed. When I finally go there'll be an awful lot of bits of me. I wonder what they'd make if anyone ever thought it worthwhile putting them together. The one thing sure is that I don't know and doubt I ever will. One has no idea what or who one is. One carries on doing things. Every so often, one takes a picture of oneself to make sure one is really there and not just the ghost of oneself on the stair.

There is a lovely, entirely vicious, comic curse of a poem by Martin Bell, titled Headmaster, Modern Style, in which Poor Joe, headmaster Conk's deputy, is described as 'emperor of pen nibs'. Of course, if I ruled the world every day would be the first day of spring, complete with paper clips.

The fact is I have no ambition to be any kind of emperor, except perhaps of ice cream. But maybe we all get to be that.

Monday, 2 April 2012

The farce of the Hungarian President

Going,gone. Hungarian President, Pál Schmitt on his way somewhere.

Some things begin famously as tragedy and end, even more famously, as farce. The case of Pál Schmitt, the President of Hungary, misses out the first stage. You can have it from the Sierra Vista Herald, from the Belfast Telegraph, or from The Financial Times and you don't need me to tell the story. Plagiarism - especially on the scale Schmitt practiced it - is cheating. He offered to rewrite his thesis, or write a new one, a process that would take him four years here. Maybe he could still try it and reapply for the post in four years' time.

President Schmitt was a tame creature of the Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, who has pulled every string to keep him in position. But there he was, gone, toppling, toppling over a day or two, but toppling all the same.

Orbán has been playing the patriotic hero with some gusto recently. It is hard to look heroic when you're in a comedy.

A friend in Italy says the Italian equivalent wouldn't have resigned. So even Hungary is a notch above Italy in at least one respect. Farce without the bunga-bunga.

Sunday, 1 April 2012

Sunday Night is... Billie Holiday 'One for my Baby' / Frank O'Hara

The Day Lady Died

It is 12:20 in New York a Friday

three days after Bastille day, yes

it is 1959 and I go get a shoeshine

because I will get off the 4:19 in Easthampton

at 7:15 and then go straight to dinner

and I don’t know the people who will feed me

I walk up the muggy street beginning to sun

and have a hamburger and a malted and buy

an ugly new world writing to see what the poets

in Ghana are doing these days

I go on to the bank

and Miss Stillwagon (first name Linda I once heard)

doesn’t even look up my balance for once in her life

and in the golden griffin I get a little Verlaine

for Patsy with drawings by Bonnard although I do

think of Hesiod, trans. Richmond Lattimore or

Brendan Behan’s new play or Le Balcon or Les Nègres

of Genet, but I don’t, I stick with Verlaine

after practically going to sleep with quandariness

and for Mike I just stroll into the park lane

Liquor Store and ask for a bottle of Strega and

then I go back where I came from to 6th Avenue

and the tobacconist in the Ziegfeld Theatre and

casually ask for a carton of Gauloises and a carton

of Picayunes, and a new york post with her face on it

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 spot

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)