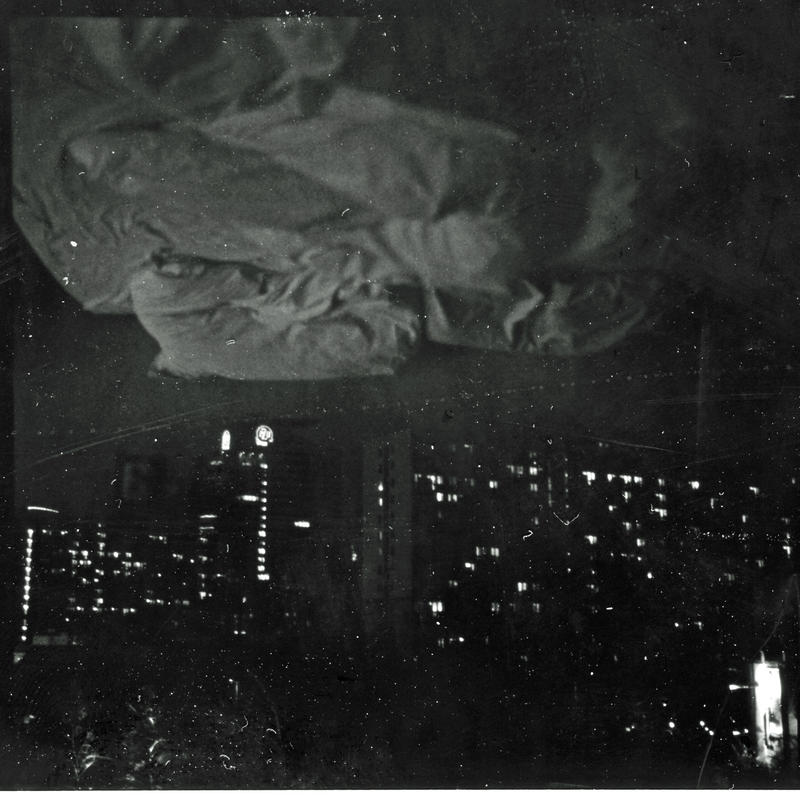

The Temptation of St Anthony by David Teniers, the Younger c 1645

All stories, however 'realistic', are driven by the motor of myth, that is to say by a mechanism of associations that provides a passing view of experiences beyond the immediate story. These myths follow certain formal patterns that we sometimes refer to by names such as genre. I don't mean exactly what Barthes does in Mythologies, but that too when all is said and done: the Marxist along with the Freudian and its variations.

In so far as we follow certain protagonists we travel with them on a journey through a universe that has its own genre rules. Incidents assume significance either because we know the rules already or because we can relate the new rules, as we come across them, to the shadows of other rules that we recall from other situations.

One of the salient features of Breaking Bad is that it operates by several rules at the same time. From Tarantino through the Coen Brothers we have become accustomed to a series of interpenetrations where broad comedy, subtle psychological nuance, direct violence, and even horror, are presented, sometimes in succession, sometimes simultaneously, in ironic, semi-detached terms.

We tend to refer to such works as examples of postmodernism if only because we understand that irony is an important element in them and that our normal categories, including those we consider most solemn, are being treated in a playful manner. The first effect of postmodernism then is an apparent removal of substance if only because we associate substance with the known, that is to say we supply our own learned backlog of depth to help us navigate. It is harder to navigate the postmodern journey.

The second effect, and I don't want to investigate this line further now because we still haven't finished watching, is that, having grown accustomed to the manner of shifting perspectives and story levels - the playfulness - we are left with a sense that there is in fact something intensely serious going on and that such seriousness is, after all, to do with us. That is the mythic level.

Given that, I want to note three almost random items, for my own sake as a kind of memo so I can think about it later and maybe return to the themes. All three are symbols of sorts.

1. Desert.

The visions of the Desert Fathers have been depicted by various Flemish and Italian artists. The mind is prone to fantastical demons and temptations. This is partly because of solitude, partly because of sensory deprivation, and partly because of the intense pursuit of an ascetic ideal. The New Mexico desert is the image we keep returning to in Breaking Bad. It is a place of death and isolation and evil. It is ascetic and it does produce demons.

2. Disability

Walter's son is disabled from birth. Walter is disabled by his character's inability to assert his own identity and, more crucially, by cancer. Hank is disabled by shooting. Jesse is beaten up more than once. All the male characters are reduced in their capacity for action. The irony is that the more Walter seems to be reduced the more transgressive and more active he becomes.

3. Demons

Demons specifically from Mexico. I doubt whether Breaking Bad is an advertisement for Mexican tourism. Granted we have heard of the highway of death, of drugs barons, of gang warfare and decapitations, but the demons that emerge from this Mexico of the enhanced imagination have a metaphysical quality. Tuco, the two brothers killed by Hank, and all the other stony-faced maniacs and killers offer a dimensionless depth that is pure myth.

One myth that constantly comes to mind is that of Faust who makes a pact with the devil and is finally dragged down to hell. Walter's pact is not quite so clear cut, nor does he desire infinite power, not at the beginning anyway, but he does have a Faustian gift. Eliot's Fisher King, crippled by a magical wound, also fits the bill in some respects. These myths are not monolithic or exclusive; they play in and out of any narrative along with other equally potent myths.

The myth mechanism - the engine - is a compound. The playing out of any single myth in contemporary terms would be banal and reductive. Interplay demands complexity and unpredictability of detail. Of Walter's final destination we are in no doubt but how he gets there is constantly surprising.

All this fits into the reading whereby masculinity and its problematic role in an insitutionalised and domesticated world is the main dynamic.

Heisenberg is no joke. Heisenberg has genius and agency. His potential is Faustian, Promethean even! But this is the early twenty-first century. This is postmodernity. The future, as has long been claimed, is female. There are no Clint Eastwoods left. There is irony, subservience, and more irony. And Heisenberg.

Yo bitch! as Jesse tends to say.